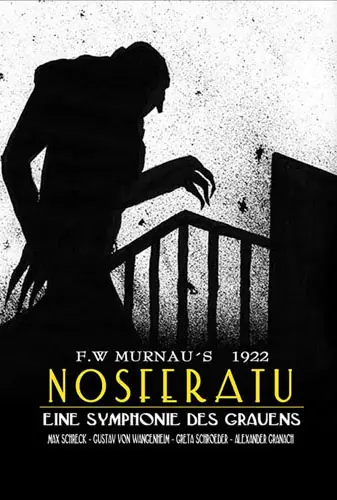

I have the dubious task of reviewing the 1922 silent film from German filmmaker F. W. Murnau, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. Dubious in the sense that I’ve just seen it for the first time and have seen Robert Eggers’ 2024 Nosferatu twice. It’s going to be hard to separate the two.

Thomas Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim) is an optimistic young man trying to provide for his handsome wife, Ellen (Greta Schröder). As luck would have it, his estate agent boss, Knock (Alexander Granach), is about to give Thomas the sale of a lifetime. All Thomas has to do is travel across the continent to Transylvania and deliver papers for the mysterious Count Orlock (Max Schreck) to sign for the purchase of a mansion next to Thomas’ house.

Dismissing Ellen’s pleas to stay home, Thomas travels to Orlock’s castle, avoiding specters, werewolves, and the locals’ warning to stay away from Orlock. Despite the locals’ warnings, Thomas journeys onward and is dropped off miles from the castle by a fearful driver. Orlock welcomes Thomas, notices a beautiful photo of Ellen, and partakes in a late-night supper. The next morning, Thomas wakes up to an empty castle and feels weak due to a mosquito bite that drains most of his blood. Meanwhile, Ellen dreams about the soon-to-be-demise of her husband, Thomas, and the creepy visage of Nosferatu.

So, let me get the comparisons out of the way. Eggers adds an hour of story to his version and does a pretty good job recreating Murnau’s version using modern cinema techniques and playing into the horror and gore that has evolved over the decades since 1922. Eggers builds upon the lore and emotional distress of all of the characters. Eggers also introduces a spiritual connection between Ellen and Orlock, which doesn’t exist in Murnau’s version.

“…Thomas travels to Orlock’s castle, avoiding specters, werewolves, and the locals’ warning to stay away…”

My approach to Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror is from the perspective of a film historian or as someone who wants to know how the magic is made. What I found fascinating was the notion of what scared people in 1922 versus 2024. Where Eggers was able to exploit darkness, shadows, and incredible sound design, Murnau had to shoot everything in daylight. Sadly, the film’s silent-movie soundtrack, recreated for the restored edition I watched, failed to add to its eerie charm.

Silent films succeed by focusing on simple yet compelling storytelling, and Nosferatu is a prime example. Touted as an unauthorized version of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and coming off the First World War, Murnau tells a story in a time when trust and naivete are tested. There are evil forces out there, and you can’t judge a book by its cover.

Sure, Count Orlock looks a little creepy…like a rat or a bat, but there’s no reason he can’t be trusted. Orlock’s murders are obscured by the plagues ravaging the 1800s. Like war, evil is conquered with the death of the innocent.

It’s funny how epics of the early years of cinema are considered indie filmmaking today. With very little advancement in cinema in the 1920s, filmmakers like Murnau were tasked with “figuring it out”—scaring audiences with images they’d never seen, making a man in rat makeup believable, and evoking deep emotions. He even throws footage of Venus flytraps and other microscopic carnivores. These techniques of Murnau are still just as valid for micro-budget filmmakers today as they’ve ever been.

Comparing Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror to Eggers’ ambitious reboot highlights the silent film’s historical ingenuity. Its evocative imagery and simple storytelling exemplify early cinema’s resourcefulness in conjuring dread. While Eggers modernizes the narrative with sound and shadowy atmosphere, Nosferatu is testimony to the always-evolving spirit of horror, reminding us how fear transcends time.

"…techniques of Murnau are still just as valid for micro-budget filmmakers today..."