The women themselves admit, “everyone has their tale to tell,” yet none are allowed to fully speak. They are dispatched by Nonaka (Takuma Otoo), their small-time hustler manager, and driven around by an assistant secretly filming their encounters for YouTube. Their lives, already commodified, are doubly violated through exposure. They could, theoretically, quit at any time. This is not the debt-bondage world of streetwalkers, but quitting never feels like a real option. Instead, they drift in neon purgatory, where day never truly arrives.

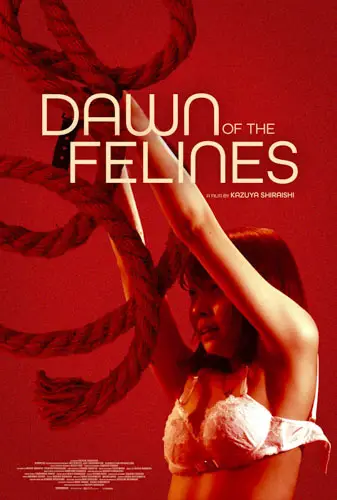

Violence hovers throughout Dawn of the Felines. Sometimes fetishized, as in bondage-club sequences; sometimes erupting into brutal reality, as when a client strangles one woman only to forgive him moments later. The camera makes the audience complicit. When women remove their clothes, the lens lingers in voyeuristic ways, often at the expense of story or character. Nudity, fetish, and softcore moments themselves are not the problem, as they fit the subject matter, but the way the images are used suggests the film shares the exploitative gaze of the men who purchase these women. Rather than expose abuse, the camera sometimes revels in it. By contrast, later on, Sean Baker’s Oscar-winning Anora will demonstrate the opposite approach: with a story along similar themes told with empathy, independence, depth, and focus rather than exploitation.

“…feels like an echo of those carrying forward some of that exploitation under the guise of gritty realism.”

The title invites comparison to Noboru Tanaka’s comedy Night of the Felines from 1972, which is one of the “pink films” that also depicted sex workers in Japan. Shiraishi’s work is made by the same studio Nikkatsu, which produced the “Roman Porno” style of film. Oddly lampooning itself, the film feels like an echo of those carrying forward some of that exploitation under the guise of gritty realism. But a more illuminating comparison lies with Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth, another nocturnal film structured around episodic encounters. Jarmusch’s cab drivers in Los Angeles, Rome, Paris, Helsinki, and New York inhabit neon and night, but he renders them with empathy, humour, and curiosity.

Night of the Felines traps his women inside stereotypes of victims, aggressors, or fantasy objects, sinking into bleak irony. The sun never rises on these women. Their night work ends, but the dawn is no new beginning, just another cycle of loneliness, deception, and survival.

"…the camera makes the audience complicit."