Not much is said, the imagery speaking for itself, greatly complemented by James Newton Howard’s searing, but never intrusive, score. I can’t remember the last time I felt so much melancholy while observing something so visually splendid. Emerald blades of grass fracture celluloid, as Burger’s camera glides through them; it swirls and dances – and then, within a blink of a lens, immerses us into dankness, with suffocating, jagged prison bars and despondent low-hanging grey clouds. Most horrors take place off-screen, yet we are well aware of them, and it makes the beautiful imagery that much more disturbing. How can nature be so indifferent to humanity’s evil? In Malick’s world, nature towers over us, intimidates us. The sun falls on all of us, indeed, both good and evil. “Perhaps one day, this will all make sense,” Franziska intones sorrowfully. No, no, it won’t, not to a rational mind, at least. They say directors play God – if that’s the case, Malick is the ultimate Deity here, casting a birds-eye-view on the eternal struggle between light and darkness.

“In Malick’s world, nature towers over us, intimidates us. The sun falls on all of us, indeed, both good and evil.”

“Better to suffer injustice than [inflict] it,” a character says, emphasizing A Hidden Life’s powerful central theme. And suffer Franz does, standing firm in his beliefs. Diehl, who’s used to playing Nazis (see: Inglourious Basterds, Allied, The Birdcatcher), puts an entirely different spin on an exploited character, infusing Franz with a deep soulfulness, a passionate resolve, a profound sadness for his family. Valerie Pachner keeps up, supporting his decision despite its implications (and the vengeful gaze of her neighbors). The rest of the cast – which includes Michael Nyqvist, Bruno Ganz, and Jürgen Prochnow, all speaking in a weirdly-fluid mix of their native German and English – absolutely shines.

Malick’s masterpiece makes a great argument that it’s the little-known heroes, as opposed to the ones we trumpet as such, that truly form the ethical foundation upon which our society still creakily rests. Malick is a true cinematic maestro, conducting the orchestra of life. A Hidden Life is breathtaking in every aspect. Welcome back, sir.

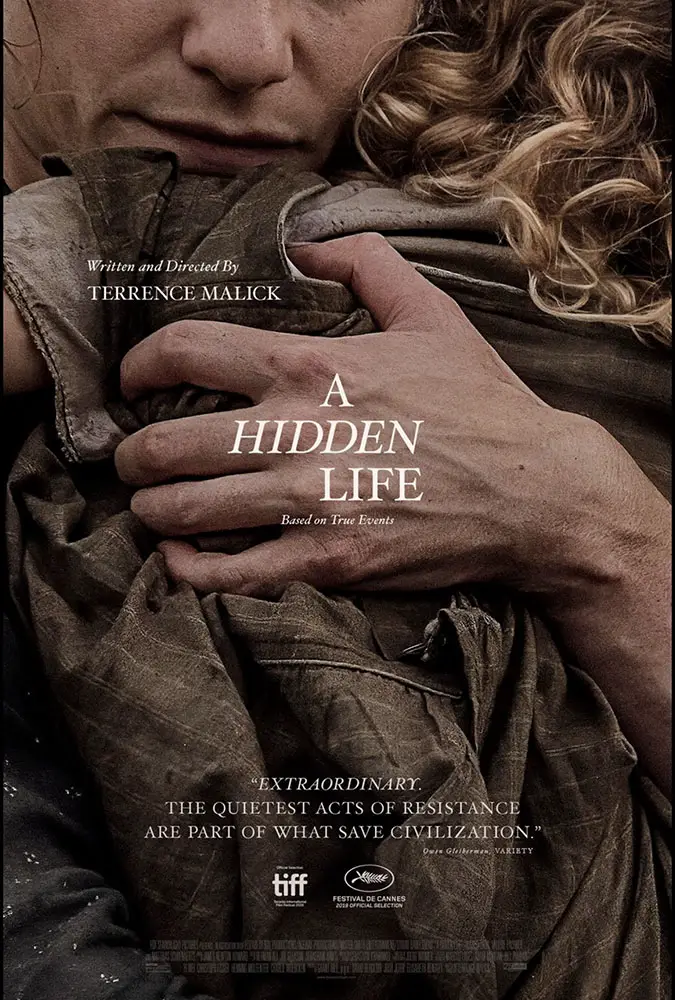

A Hidden Life screened at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival and the 2019 AFI Fest.

"…a monumental achievement, on par with the filmmaker’s best work"

Can’t wait to see this . I’m sure it’s better than Scorsese and his bloated boring miscast mob movie .

Hey Steve, I agree with you about it almost certainly being better than Irishman…but I did still like that film for various reasons, mostly having to do with the way that Marty has “slowed down” in his older age. The sensitivity that he brings to his subjects now are more contemplative than ever before, and more “integrated” into the screen action rather than relying on speed, action, editing, and dialogue. All of them have worked for him sure, and they are great too, but this shows a maturity in his style that hasn’t always been there. Irishman was his swan song of that genre, we’re all pretty sure, but if he does go on to make more films, or produce them, let’s hope he takes his additional sensitivity with him into those works.