What a wondrous, enigmatic career Terrence Malick has had! After directing two masterpieces – Badlands in 1973 and Days of Heaven in 1978 – he disappeared for two decades. The filmmaker resurfaced briefly in 1998 with existential war drama The Thin Red Line, and then again in 2005, with his take on the Pocahontas story, The New World. Seven years later, Palm d’Or winner The Tree of Life ignited a sudden sequence of hit-and-miss films: To the Wonder, Knight of Cups, and Song to Song. His signature trademarks – a laconic script, stark juxtapositions of intimate vs. epic and mundane vs. ethereal, and a camera that quite literally fuses with the wind itself – reached the precipice of self-parody. One more misfire could have put the great auteur’s cinematic oeuvre under threat of becoming blemished by its own embellishments.

“…Franz is torn by a moral quandary. Should he serve his nation… or listen to that ‘still small voice’ in his soul…”

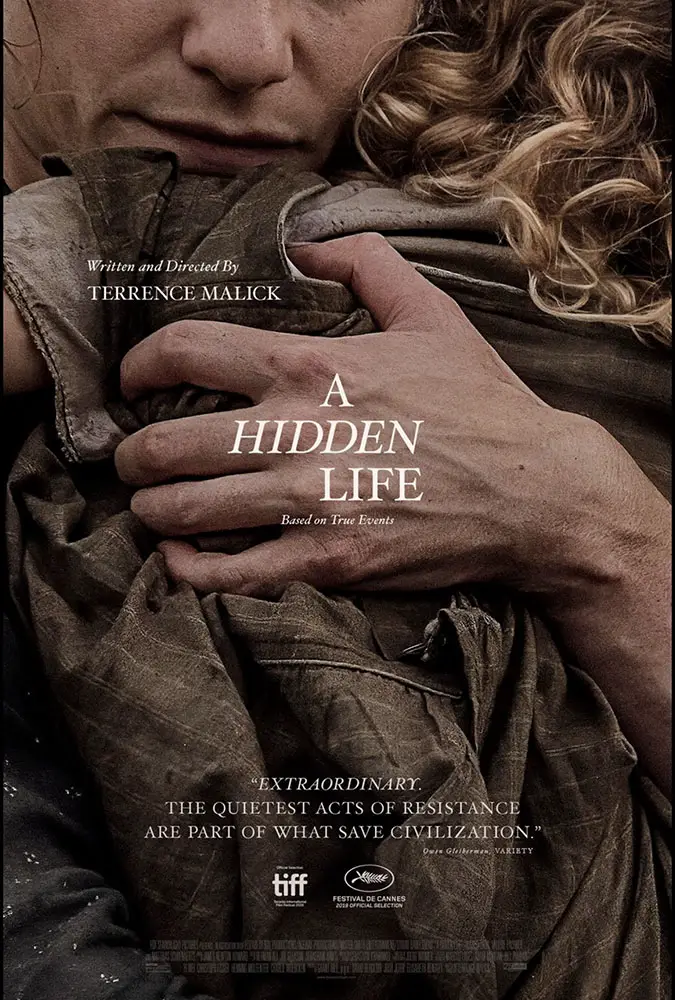

To say that A Hidden Life marks Malick’s return to form would be a major understatement. For three hours, the filmmaker and his cinematographer Jörg Widmer cast a hypnotic spell, drawing us into a stunningly beautiful, heartbreakingly dismal and deeply poetic world. It’s a treatise on humanity itself, on the evil within us, the tiny spark of hope and stoicism at its center – personified by August Diehl’s remarkable performance – resembling a dying ember. Though set during the horrors of WWII, A Hidden Life couldn’t be more timely. A monumental achievement, on par with the filmmaker’s best work, it deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as Come and See, Apocalypse Now and, yes, The Thin Red Line.

The film (which is based on a true story) starts a few years before the war, in an idyllic Austrian village surrounded by stunning vistas. Franz (Diehl) and his wife Franziska (Valerie Pachner) lead blissful but hard-working existences, imbuing their little girls with proper values. War creeps in. While their neighbors don’t question their allegiance to the cause, to their country – who are they, after all, to defy authority? – Franz is torn by a moral quandary. Should he serve his nation, spurred by the blessings of local priests, or listen to that “still small voice” in his soul, one that can’t find meaning in the committed atrocities? If he does the former, he will go against everything he stands for. If he does the latter, he will be deemed a traitor and lose his family, who, in turn, will forever be shunned by their community.

"…a monumental achievement, on par with the filmmaker’s best work"

Can’t wait to see this . I’m sure it’s better than Scorsese and his bloated boring miscast mob movie .

Hey Steve, I agree with you about it almost certainly being better than Irishman…but I did still like that film for various reasons, mostly having to do with the way that Marty has “slowed down” in his older age. The sensitivity that he brings to his subjects now are more contemplative than ever before, and more “integrated” into the screen action rather than relying on speed, action, editing, and dialogue. All of them have worked for him sure, and they are great too, but this shows a maturity in his style that hasn’t always been there. Irishman was his swan song of that genre, we’re all pretty sure, but if he does go on to make more films, or produce them, let’s hope he takes his additional sensitivity with him into those works.