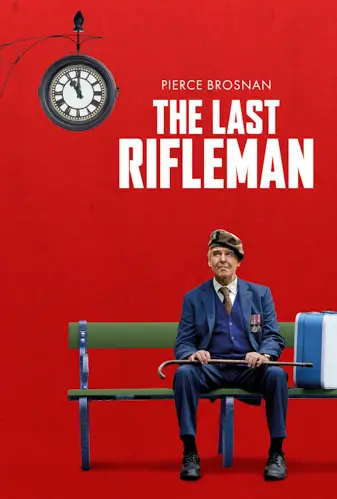

If you’re craving an old-fashioned, inspirational, small-scale story “like they don’t make ‘em anymore,” look no further than Terry Loane’s The Last Rifleman. While it may resort to every cliché in the book, its heart is in the right place, its intentions are honorable, and its lead is fantastic. Nothing wrong with a good ol’ cup of tea if you’re in the right mood.

WWII veteran Artie (Pierce Brosnan) resides at a home for the elderly in Northern Ireland. Haunted by nightmares, he visits his near-catatonic wife, reminiscing about the good old days as he feeds her pudding. When she finally passes, he decides to embark on a journey to attend the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings in France. War medals in tow, he escapes from the confines of the care home in a laundry service van.

On the way, he encounters strangers, both kind and mean, but mostly kind. Young punks harass him on the street before a good samaritan taxi driver helps him. When Artie pulls out his wallet to pay for the ride, the cabbie states somberly, “Put that away. Never had a D-day veteran in me car before.” A young man is impressed by Artie’s past encounter with Ennio Morricone; they later hitchhike together.

More hijinks, if you can call them that, ensue. Artie’s diabetes kicks in; a can of Coke saves him. His passport is out of date, preventing him from getting on a flight to France. Feeling pity for the man, Juliette (Clémence Poésy) smuggles him in via RV, and then ship, and then, um, another RV, and bus. They form a deep bond as she’s going through heavy sh*t of her own.

“…war medals in tow, he escapes from the confines of the care home in a laundry service van…”

One of the film’s highlights is also kind of a cliché. Artie meets former Nazi soldier Friedrich (Jürgen Prochnow), of whom he’s instantly and understandably apprehensive but who later declares, “It’s a shock to learn you’ve lost the war. It’s a greater shock to learn that you’ve been on the wrong side.” Not exactly a profound sentiment, but a touching scene between two (acting) veterans nevertheless.

After another conversation with Ct. Lincoln Jefferson Adams (John Amos), the “second African American on Omaha that day,” Artie reveals a haunting part of his past to a reporter who’s been following him this entire time. The touching finale almost transcends all the truisms that came before, with Artie realizing that he didn’t have to travel far to get what he sought.

It’s all very granola and sentimental, a path well-trodden. Straightforward, heart on the sleeve, what you see is what you get. The flashbacks, as they tend to be, are cheesy and unnecessary, as is the subplot of the folks at the care home freaking out about his disappearance. (He ends up on the news? C’mon, really?) Composer Stephen Warbeck’s strings frequently sweep in to accentuate the emotional beats and remind the audience how to feel. “We’re all living with ghosts” is the central Big Theme, and it just doesn’t resonate as much as it’s intended to.

Thank God for the wonderful Brosnan. At 71, he plays someone who’s 21 (“and three-quarters”) years older with aplomb, his voice a gentle rasp, his walk stooped and shaky, each mannerism perfect. “They used to call me the artful dodger,” he reminisces. “Even when I did take a shell, I survived… I’ll be fine.” It’s refreshing to see a film made with an older demographic in mind, something that doesn’t happen too often these days.

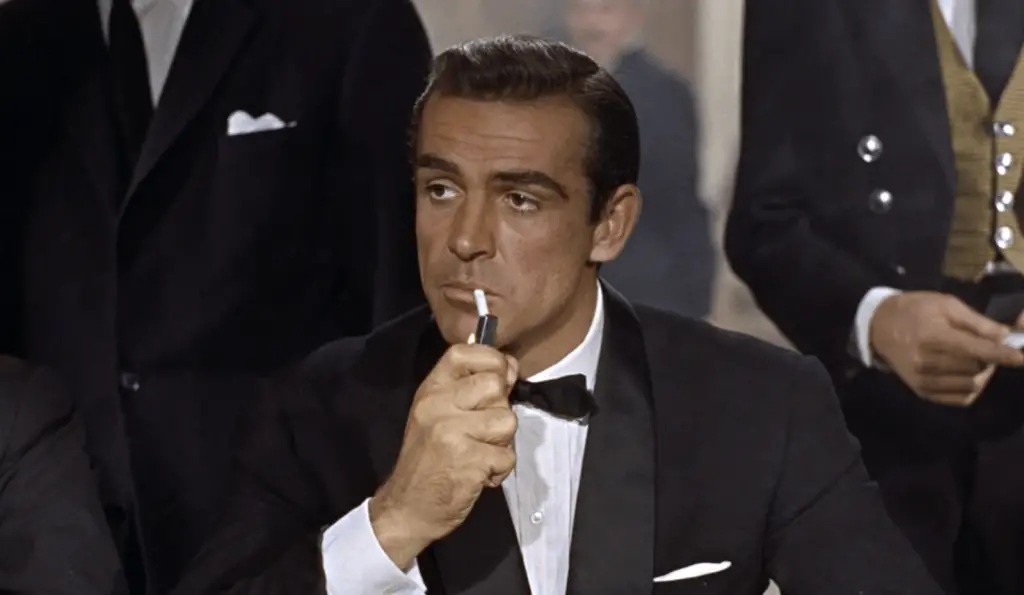

Seeing the former James Bond play a WWII vet is worth the price of admission by itself. Go see The Last Rifleman to support an acting stalwart – and, for lack of a better word, “traditional cinema.” Films like this are fast becoming the last of their kind, just like the titular hero.

"…its heart is in the right place, its intentions are honorable, and its lead is fantastic..."