“What’s the worst thing you’ve ever done?” It’s a question asked by two characters and it forms the central theme of Chris Silvertson’s adaptation of Jack Ketchum’s novel. The movie opens on a pair of boots tramping awkwardly through sparse woods. They belong to Ray Pye, a budding, teenaged psychopath, who stumbles across a young woman emerging, completely naked, from an outhouse. Longing for more, Ray and his friends, Jen and Tim, spy on the girl and her friend as they sunbathe by the lake, and camp at the fire. When Ray discovers—or believes that he discovers—the girls to be lesbians, this perception causes him to decide, spontaneously, to murder the pair. Jen and Tim keep his secret—held in thrall and admiration and more than a little bit of fear—for four years.

Ray and his friends get older, but they don’t exactly grow up. Ray continues to be a slave to instant gratification, fashioning himself as a ladies’ man, replicating his look as a cross between James Dean and Elvis (though, in the film’s unspecific time period, he resembles Robert Smith more than anyone else), and continues to stuff crushed beer cans into his boots to make him taller. All of these affectations fail, ultimately; the look is odd and the cans in his boots give him a loping, drunken limp—more awkward than cool. And his friends are starting to realize that they’ve been worshiping a straw man all along. As Ray’s façade begins to shatter before Jen’s, Tim’s and his own eyes, his violent temper tantrums begin to reveal the damaged psyche beneath, leading to a violent and expected conclusion.

Intense writer Ketchum is a hot commodity lately. First came the faithful and exquisitely disturbing adaptation of his “The Girl Next Door,” and now Silvertson’s take on his youth-gone-nuts story. Like “The Girl Next Door,” “The Lost” was inspired by a horrific true story, and Ketchum excels when bringing terrifying violence into seemingly-serene environments. Though the movie’s budget didn’t allow for a faithful recreation of the Viet Nam-era of the early ‘70s—the title actually refers to the displaced youth who grew up without fathers or older brothers and were left to mature on their own under the ill-advised and miscomprehended guidance of movies and television—Silvertson manages to place the film in a town that is not time-bound. The older cars and the drive-up restaurant give it a ‘50s flavor, while the youthful drug use call to mind more contemporary coming-of-age dramas. So rather than Ketchum’s specific time-frame, the film version of “The Lost” is telling its audience that Ray Pyes are everywhere. Be very wary of the cool guy with younger acolytes. What happens when people stop admiring him? What happens when he loses the control he’s convinced he holds?

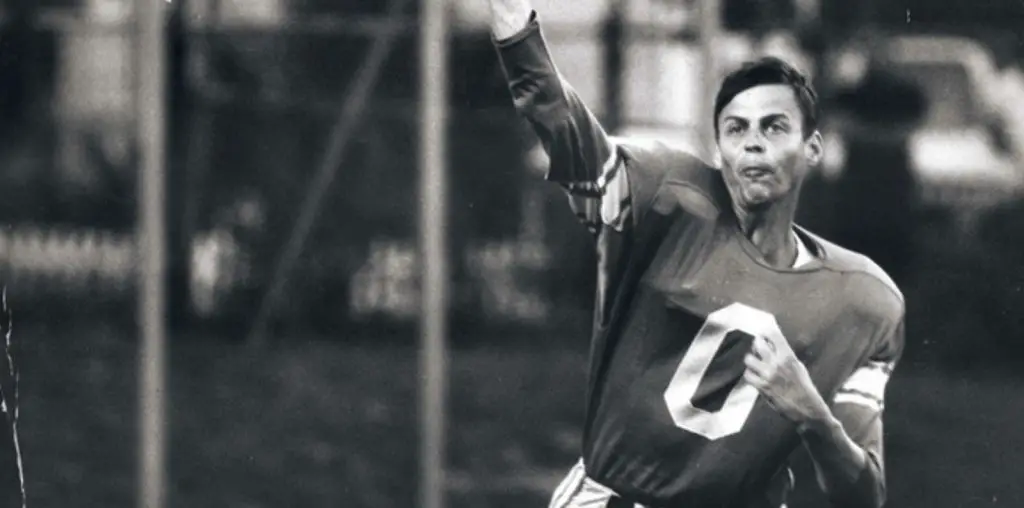

The performances are uniformly terrific, with Marc Senter as Ray being the central figure and standout. A good thing; without a believable Ray Pye, “The Lost” would have fallen utterly apart (much like Silvertson’s much-maligned “I Know Who Killed Me” and his execrable lead in that one). Senter isn’t afraid to make Ray appear foolish and uncool and immature—or even kind and concerned and unsure—making for a very rounded little sociopath. By the time he finally loses his mind, the audience is completely invested in Ray Pye. He isn’t a cartoony villain filled with menace. He’s a guy in his early-20s with no ambition beyond throwing his next party and completely invested in his “cool” self-image. Ray Pye will be perpetually seventeen, mentally and emotionally, with all the imbalance and insecurity that goes with it.

The supporting characters and their intertwining subplots aren’t lost either (with the minor exception being Tim, who never seems that central to the story and is just “there” for the majority of the film). From Michael Bowen’s Detective Schilling, the cop who is always one step behind Ray, to the May-December romance going on between Sally (Megan Henning) and Ed (Ed Lauter), Schilling’s former partner, to Ray’s lovers—and victims—conflicted Jen (Shay Astar) and Kath (Robin Sydney), we’re dealing with people, not stock characters. Which is refreshing and satisfying—making the violent conclusion that much more distressing.

If Silvertson makes any missteps it’s in some awkward, rushed blocking of the more casual moments and the ill-advised drug sequences shot through with grain and scratches to simulate Super-8 film. The former shows the budget fraying along the edges and giving the movie an amateurish feel; the latter just yanks the viewer out entirely by calling attention to itself—“look: cool stylistic photography!” “The Lost” is best when the characters interact and we watch Ray’s world slip away from him. Ultimately, “The Lost” is much more than the sum of its parts and is definitely worth repeated viewings if only for the remarkable depth of storytelling and use of quiet moments to underscore the louder ones.

The Anchor Bay DVD comes with the usual extras—outtakes, trailers for other movies, some audition footage, which is nice, and an excited commentary by Ketchum and fellow writer Monica O’Rourke, who discus the themes of the novel and how they translated to the film. It’s a unique perspective, having the original writer (accompanied by another talented scribe) and Ketchum is obviously very satisfied with the end product, even when it deviates from his original text. Which, in itself, speaks volumes for this particular cinematic animal.