BOOTLEG FILES 167: “The Stranger” (Luchino Visconti’s 1967 adaptation of the Albert Camus novel).

LAST SEEN: At the Rome Film Festival in October 2006.

AMERICAN HOME VIDEO: None.

REASON FOR DISAPPEARANCE: A long-standing problem regarding the rights to the Camus source material.

CHANCES OF SEEING A DVD RELEASE: Not likely at this time.

Albert Camus’ existential literature and Luchino Visconti’s grandly melodramatic cinema existed at opposite ends of the artistic spectrum. Oddly enough, they managed to overlap for Visconti’s ill-fated and long-forgotten 1967film adaptation of Camus’ “The Stranger.”

“The Stranger” came at a rough creative time in Visconti’s career. His 1960 feature “Rocco and His Brothers” was a major international success, but his next film was a professional and personal catastrophe: the 1963 production of “The Leopard,” which was released in a haphazardly edited and poorly dubbed version by 20th Century Fox. Visconti repudiated that version (the director’s cut would remain unseen for three decades), but the box office failure of “The Leopard” was considered a slam against him. His next film, the 1965 feature “Sandra,” was a critical and commercial failure.

“The Stranger” marked a challenge to Visconti, as the Camus text was a first-person narration by an enigmatic figure caught up in a viciously absurd state of affairs that culminates in a one-way trip to the guillotine. The book obviously did not lend itself well to cinematic adaptation, yet producer Dino De Laurentiis felt Visconti could pull it off.

From the beginning, “The Stranger” was marked with problems. Camus set the book in French-occupied Algeria before World War II. Visconti, however, wanted to update the setting to Algeria at the start of the war for independence. This idea would bring a political edge to Camus’ vision of a man estranged from his world (in this case, a Frenchman estranged from the Algiers where he lived for most of his life). The updated timeline would also cash in on another Italian film about Algeria’s war for independence, Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 “The Battle of Algiers.”

However, Camus’ widow (the author died in a car crash in 1960) vehemently opposed Visconti’s plan. Perhaps unknown to Visconti, Camus was not supportive of the Algerian push for independence from France and actually wrote that the struggle against French colonial occupation was part of a “new Arab imperialism” coordinated by a Soviet-Egyptian axis to “encircle Europe” and “isolate the United States.” Ironically, Camus opposed to any cinematic version of his books and his widow only agreed to have “The Stranger” filmed because of Visconti’s participation.

Forced to keep the film in its late 1930s setting, Visconti then had the task of recreating that era in Algiers, where “The Stranger” set up location. He successfully persuaded the local officials to tear up a paved street and install trolley tracks for a sequence using that antiquated form of transportation. The local officials acquiesced, but were probably not pleased when Visconti barely used the trolley in the film. In fact, Visconti barely used Algiers as a central element in the film – he chose to frame the majority of his location footage in close-ups and medium shots, thus blocking the city from view.

But the biggest problem turned out to be in the casting. The Italians Visconti and De Laurentiis agreed the film would be a French-language release, but getting a French actor to play the central character of Mersault was a pain. The first choice for the role was the handsome French star Alain Delon, who starred in “Rocco and His Brothers” and “The Leopard,” but Delon was not interested in “The Stranger.” Illogically, De Laurentiis and Visconti decided to cast Italian leading man Marcello Mastroianni as Mersault. But Mastronianni didn’t speak French, so his performance was dubbed by a French actor.

Camus’ book opens with one of the most disturbing and enigmatic lines ever written, with Mersault commenting abstractly on the receipt of tragic news: “Mother died today. Or was it yesterday?” Yet Visconti provided the film version with a new opening: a handcuffed Mersault is brought by the police to a magistrate’s office, where he is asked about the crime that brought about his arrest. From there, the film flashes back to the Camus opening, with Mersault getting on the bus to the old age home where his mother lived out her final days. It was only on the bus that the famous opening lines were spoken. The new opening made no sense – the celebrated opening was jettisoned and the carefully-constructed storyline was ruined by tipping off Mersault’s fate before the credits begin.

For the rest of the film, Visconti is faithful to the Camus book. Even Time Magazine noted the fidelity, commenting that the film “follows the action of the novel with hardly a comma missing.” But while the action is followed closely, the emotional nature of the book is nowhere to be found on screen. The problem for that can be rested solely on Mastroianni’s shoulders.

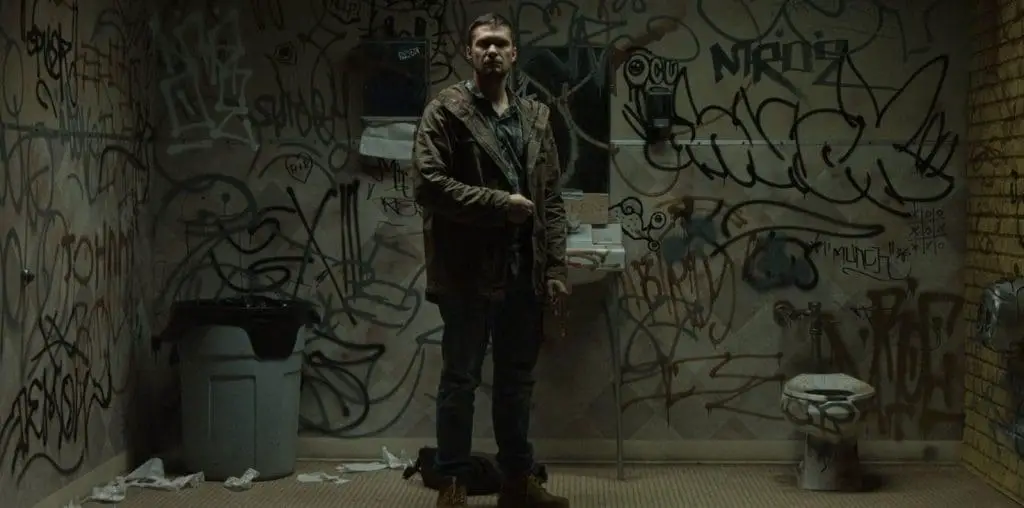

In the Camus book, Mersault is a cipher – he is disconnected from his surroundings, which makes his fate jolting because his society has no idea how to deal with a man who doesn’t seem to obey the basic protocols of emotional behavior. In the film, however, Mastroianni’s Mersault is charming and affable. He’s a good-looking man who is popular with his colleagues and neighbors, and he is blessed with a gorgeous girlfriend (Anna Karina, who has little to do in the film but look lovely). By the time Mersault is brought to trial for shooting the Arab youth, the prosecution based on the notion that he is a remorseless freak makes no sense. Mastroianni’s personable Mersault is not the cold, blank personality without feelings or concerns, as the prosecution insists – one needs to wonder whether the prosecutor had Mersault confused with someone else.

By the film’s conclusion, Mastroianni abruptly switches personas. His death row cell sequence finds him emoting with a wild, hammy intensity that was never present earlier. Much of this sequence is without spoken dialogue (the internal monologue is recited on the soundtrack), so Mastroianni conveys the character’s thoughts with broad acting shtick: rolling eyeballs, clenched jaws, fingers scratching the stone walls, etc. By the final moments, when Mersault hopes the crowds around the guillotine greet him with shouts of contempt, the character’s transformation is so abrupt that is appears he is suffering a mental breakdown – and that was clearly not Camus’ intention.

“The Stranger” premiered at the 1967 Venice Film Festival, with Visconti snagging a Golden Lion nomination as Best Director. The film arrived in American theaters in December 1967 via Paramount Pictures. Unfortunately, the U.S. print had problems: the New York Times, in its harshly negative review, pointed out the film’s “typographical-error-laden English subtitles.” Critical appreciation was divided, with the Times dismissing it as “stodgy and colorless, even in color” while Pauline Kael of the New Yorker naming it among the three most important films of that year (“Bonnie and Clyde” and Orson Welles’ “Chimes at Midnight” were the other two). An English-dubbed version was later released, but that adaptation was marred with weak voice performances that rarely matched the dramatic tensions on-screen.

“The Stranger” was nominated for the Golden Globe Award as Best Foreign-Language Film. It lost to Claude Lelouch’s “Live for Life,” but most Americans didn’t know about that because the ceremony was not telecast. It seemed the FCC accused the Hollywood Foreign Press Association of telling the winners about their victories ahead of the ceremony, which was considered to be an act of “misleading the public about the integrity of the awards process.” NBC, which was supposed to telecast the awards as a live event, dropped the show and the other networks would not touch it.

Visconti rebounded from “The Stranger” to direct two of his most popular films, “The Damned” in 1969 and “Death in Venice” in 1971. Over the years, the initial prestige surrounding “The Stranger” evaporated.

So where is “The Stranger” today? It appears the film is stuck in a seemingly endless legal mess surrounding the rights to the Camus source material. Outside of a few Visconti retrospectives at non-theatrical venues, “The Stranger” has not been made available for commercial viewing since its original run. Bootleg videos that appear to come from a 16mm print of the English-dubbed release can be found, but most of them are not satisfactory (it’s a pan-and-scan version taken from what appears to be a second generation dupe).

If “The Stranger” returns, it would require considerable restoration including new subtitles. But even in a cleaned-up version, it would probably remain little more than second-best Visconti. And considering the wealth of prime Visconti films, who needs to settle for second-best?

IMPORTANT NOTICE: The unauthorized duplication and distribution of copyright-protected material is not widely appreciated by the entertainment industry, and on occasion law enforcement personnel help boost their arrest quotas by collaring cheery cinephiles engaged in such activities. So if you are going to copy and sell bootleg videos, a word to the wise: don’t get caught. The purchase and ownership of bootleg videos, however, is perfectly legal and we think that’s just peachy! This column was brought to you by Phil Hall, a contributing editor at Film Threat and the man who knows where to get the good stuff…on video, that is.

Discuss The Bootleg Files in Back Talk>>>