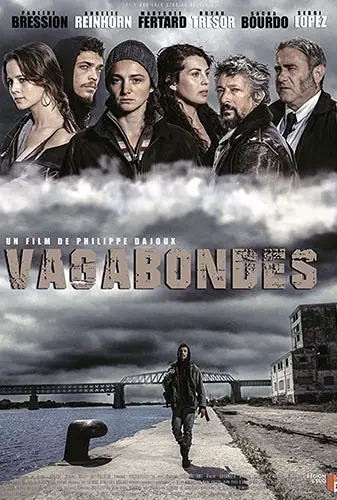

French films never seem to be in much of a hurry to express some gentle nuance of life, and this can be a problem for American audiences. It’s probably something we should collectively work on, but we’re all ragingly impatient. Not only are French filmmakers fond of drawn-out incremental shades of melodrama, but also, they love repetition. I noticed this when I saw Amélie the first time and found my mind wandering during the endless Groundhog Day-esque renditions of the coffee shop scene. Face it, it’s us, not French film. We are at fault and need to own the fact that Americans have the attention span of a gnat that’s been recently engulfed in flames. So, correcting for this American character flaw, let’s unpack Vagabondes, Phillipe Dajoux’s languid film about life on the street in France.

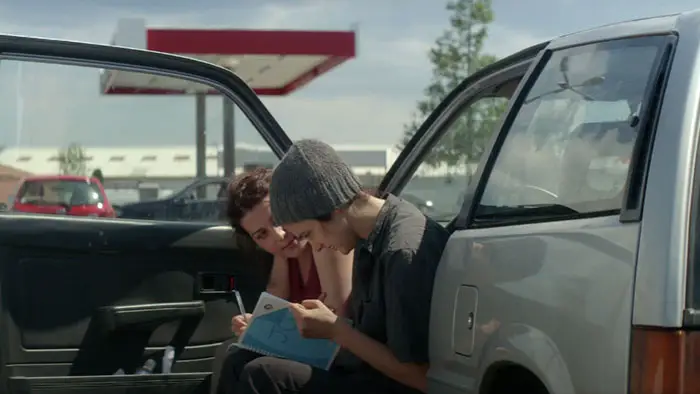

The story follows four people who live on the street, in two parallel threads. The film opens on a young man named Soha (Bryan Trésor), who accidentally shoots his drunken stepfather while defending himself from an attack by the man. He goes on the run, avoiding the police, family, and friends as he goes to ground, living rough for two years. One night he encounters a group of men who are forcing a drugged young woman into a car. He fights them off, takes their money and their car, and drives off with the woman, Anastasia (Marysole Fertard).

The other track of Vagabondes follows the lives of Jo (Pauline Bression), Faustine (Aurélie Reinhorn), and Miloud (Sacha Bourdo), who live in the parking lot of a big box store. Jo lives in her car, which broke down here two years ago. Miloud is an older man with mental illness who claims a drafty shed on the property for himself. Faustine is a young woman of means, a writer who fancies herself light in the “life experience” department. In the interest of improving her writing, she decides to live with the homeless for a space of time, hoping to give herself some emotional depth from experiencing those hard miles. It’s an incredibly stupid, tone-deaf affectation that could only originate in clueless privilege.

“…when she learns that Faustine is essentially faking homelessness, she is infuriated…”

When Faustine is caught stealing tampons from the store, Jo talks the manager, Marcel (Sergi López), out of pressing charges by saying that Faustine is her cousin, and promising him it won’t happen again. Marcel is grumpy, but ultimately sympathetic to Jo, Faustine, and Miloud, and agrees to forget the incident and allow them to all stay in the parking lot (this, then, also is something that would go differently in the good old US of A). Jo is filled with rage about her life, and when she learns that Faustine is essentially faking homelessness, she is infuriated and refuses to share her shelter. She only changes her mind when Faustine agrees to teach her to read and write.

The only quality these characters share is that none of them feel they can go home. Life on the streets, for them, is preferable to what might await them elsewhere. This film doesn’t flow linearly, as a domestic audience might expect. It also doesn’t follow a conventional three-act structure through seismic character transformations. What Dajoux and his cast accomplish, with great skill and passion, is to share the experience of these lives at the margins of society.

Emotions are captured beautifully: Jo’s rage and helplessness, Miloud’s confusion, Soha’s fear and regret, Anastasia’s desperate need to avoid abandonment, and Faustine’s wrong-headed notions about the world outside her bubble of wealth. Relax and settle into something paced a little differently. While watching Vagabondes throw off your American impatience, and ruminate on the beauty and the sadness in lives unlike your own.

"…the only quality these characters share is that none of them can go home."