Ava DuVernay has undoubtedly become a force to be reckoned with in Hollywood. Her work tends to focus on the plight and history of African Americans; she continuously demonstrates a profound understanding of and passion for her culture. Whether it’s writing and directing a show, helming Oscar-nominated features, documentaries, or music videos, DuVernay is a crucial voice in a still shockingly underrepresented demographic.

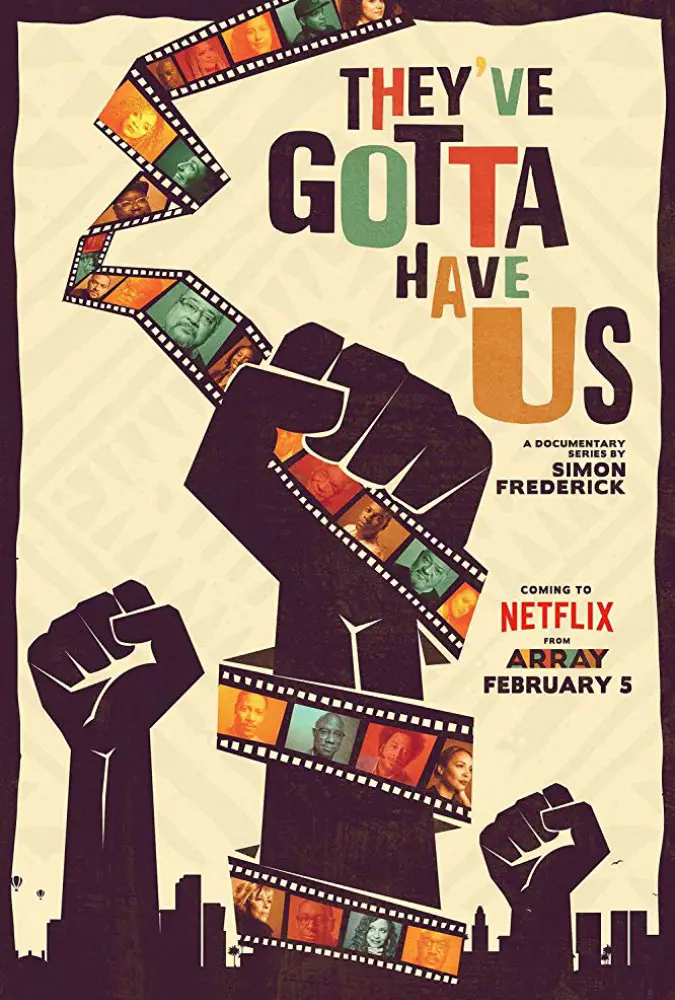

DuVernay is distributing Simon Frederick’s 3-part documentary series, They’ve Gotta Have Us, via Netflix to coincide with Black History Month. The show aims to cover the history of Black Cinema, featuring interviews with legends like Diahann Carroll, Harry Belafonte and John Singleton. Each episode begins with a montage of Lupita N’yongo, Mahershala Ali, and Viola Davis winning their respective Oscars, signifying hope and optimism for the future.

“Find out how black filmmakers finally won themselves the space to speak with their own voice and express all facets of their humanity,” Frederick promises. He delivers on that in a documentary that is surface-level considering its subject, but supremely entertaining and crammed with fascinating talking heads. It will leave you marveling at the impact of African American culture on cinema and hoping that the paradigm really is shifting.

“… aims to cover the history of Black Cinema, featuring interviews with legends like Diahann Carroll, Harry Belafonte, and John Singleton.”

“Legends and Pioneers,” the first episode, begins with the infamous Oscar snafu. La La Land – an all-white film about jazz – was awarded best picture, when in fact, Moonlight – an all-black movie about what it means to be gay and black in contemporary society – won. The implications of that mess alone could make for a riveting feature-length film, but Frederick’s reach is much larger. After an overview of the current state of Black Cinema, he delves into the tumultuous history of the “black presence in Hollywood,” when African Americans were relegated to playing butlers, thugs, and comic relief characters.

This episode skips through some crucial milestones – there is no mention of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. But it does provide a compelling overview of the black actors’ struggle to be heard. Hattie McDaniel getting up from her segregated seat to accept her Oscar for Gone with the Wind, the first won by a black entertainer, is a powerful moment. 91-year-old legend Harry Belafonte waxes lyrical about the not-so-good ol’ days. All in all, the episode does a decent job in revealing how black filmmakers gradually overcame (some) prejudice to become a powerful voice in contemporary cinema.

Episode two, “Black Is Not a Genre” picks up with Spike Lee‘s legacy. Though the man himself doesn’t make an appearance, auteurs like John Singleton and Ernest Dickerson discuss how Do the Right Thing directly influenced Boyz n the Hood and Juice, respectively. The idea of “black masculinity” is touched upon, especially evident in the 1990’s “hood movies.” Frederick reveals how Hollywood relapsed to portraying black people as addicts and thugs. He traces the trend to the Blaxploitation films of the 1970’s – some of this episode’s most vibrant bits – when Pam Grier reigned supreme as the vixen not to be messed with. This led to the rise of the 1980’s black comedians, such as Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy – and, in turn, to the emergence of Will Smith and Martin Lawrence in the 1990’s.

A fascinating subject the documentary broaches is that of white directors directing black films. Taylor Hackford talks about finding a black writer to write Ray. “He understood the voice that I couldn’t understand,” the filmmaker says, “that I don’t have on my palette, on my tongue.” Whoopi Goldberg recollects how Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple was boycotted by the NAACP and failed to win any of its 11 Oscar nominations, despite 9,000 black actors gracing the screen.

"…hoping that the paradigm really is shifting."