What do lofty terms like “human dignity” mean in today’s world? Have they been relegated to the realm of speculation and theory by the widespread injustices prevalent in the current socio-political scenario, or do they still exist in some rotting, fragmented form? British-Palestinian writer/director Farah Nabulsi launches a striking examination of these concepts in her short film, The Present, a fairly simple story of one day in a family’s life, underlined with a powerful subtext that does all the heavy-hitting.

Yusef (Saleh Bakri) is a man on a mission. Against all odds, he has to get his wife (Mariam Basha) a present for their wedding anniversary. Their refrigerator is an old one which does not work properly anymore, so he decides to surprise her with a new one. Accompanied by his young daughter Yasmine (played by Mariam Kanj), Yusef sets out to make his wife’s day. He has terrible back pain, which forces him to keep taking painkillers, but he has none to take with him on this trip. Hoping that it will be a quick journey, he decides to risk it. However, everything goes wrong during the outing, so his back gets progressively worse throughout the day. Deceptively structured as the exploration of a microcosm of the contemporary Palestinian condition, The Present takes us into a Kafkaesque nightmare in which going to the store means subjecting yourself to all kinds of bureaucratic absurdities.

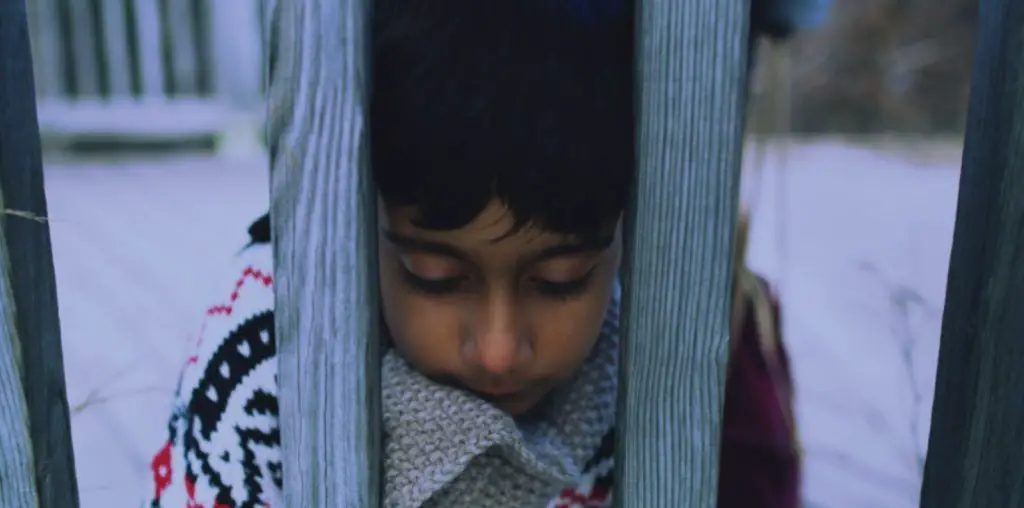

Nabulsi conducts a scathing indictment of the restrictions in effect all over Palestinian territories, focusing on the West Bank where citizens have to navigate the labyrinthine chaos of military checkpoints, curfews, segregated road systems for different communities, a separating wall, and a constant reliance on identifying documents for individual subjectivity. She presents a dystopian society that is rooted in reality, identified by divides and walls. From the opening sequence, we can see clumps of unenthusiastic bodies shuffling along with these constructed barriers. The camera emphasizes claustrophobia to remind the viewer that these people do not have the liberty of personal space.

“…he has to get his wife a present for their wedding anniversary.”

The camera tragically frames Yusef and Yasmine through another frame, that of the checkpoint’s metallic mesh. The movie presents the father and the daughter through the perforations of an object that signifies authoritarian control through the cracks in the system. It is painful to watch them getting harassed by Israeli soldiers who ask Yusef to strip naked in front of his daughter, disregarding the fact that there is a real human in front of them. Even though they eventually let them go, they only do so after holding them in makeshift cells for no good reason.

The main visual technique is to subvert voyeuristic expectations by making the viewer sit through recurring abuses of power. Thanks to all the meaningless checkpoints, Yusef has to roll the brand-new refrigerator back home on a trolley. We see him struggling with his bad back but are as helpless as him, not being able to do anything about the discriminatory system he exists. On the cusp of reaching home, he is stopped at the same checkpoint again. After being humiliated, he passes through, but the refrigerator does not fit the checkpoint’s small doorway, and they are not allowed to go through any other way. This is the apotheosis of the film’s greatest achievement: translating absolute frustration to the cinematic medium.

Near the end, Yasmine commits a poignant act of transgression, one that proves how effective The Present is. The filmmaker brilliantly uses the innocent figure of a child who has had enough with the unnecessary violence of the world of adults as the voice of reason. She wants to get home.

"…a striking examination..."