The titular character of writer-director Saxon Moen’s The Debt of Maximillian is the latest in a long line of degenerate gamblers spiraling out of control for our viewing pleasure. From Dostoyevsky’s The Gambler, to the 1974 James Caan movie of the same name, to the recent Uncut Gems, a man hopelessly addicted to living on the fulcrum of glory and disaster is as rich a character as can be. Poke at him all day long, get him in a room with his mother, his medical records, and the dog that ran away when he was eight, and you still won’t know why it is he does the things he does.

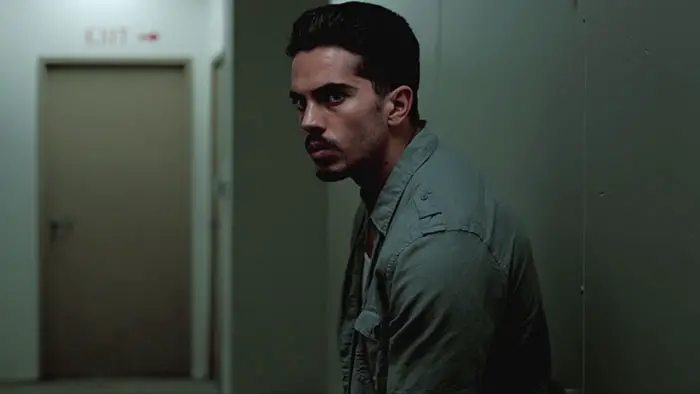

Max (Travis Lee Eller) has a job in sales, a pregnant wife, and a daughter, all wrapped up in a suburban home. It may not be the most exciting life, but if you have a hobby or two, you can live with it. Unfortunately for Max, his hobby is sports gambling. He could have picked guitar or whittling, but he had to go with gambling. When was the last time you heard of a whittler getting in a back alley fight?

“He’s taking on debts to pay off old debts…”

When we first meet Max, he’s already in the deep end of the pool. He’s taking on debts to pay off old debts and putting everything on football games for an easy out that never comes. Before long, Max comes into some cash, illicitly, of course, and his troubles become greater. As these kinds of stories usually go, you’re watching a guy willingly dig his own grave. It is as if Max believes that by digging long enough, he’ll pop out the other side of the earth without a speck of dirt.

What holds The Debt of Maximillian back is some rigid acting and conformist dialogue, which doesn’t even conform to the good stuff. For example, a scene where Max is saying goodnight to his daughter, and she innocently asks him where good dead people go versus the bad. You’ve seen it before—it’s a transparent attempt at an emotional crescendo, where Max’s degeneracy is contrasted with the raw goodness of a child. Because you see it coming, you move out of the way, and it misses. Most of the dramatic elements have this same level of transparency, which it keeps the emotional beats from landing.

On the bright side, some of the most sacred storytelling values are respected, in that Moen doesn’t try to redeem Max, make him particularly relatable, or give him a hacky character arch. There’s great value in the descent itself and the nuances therein. It’s a familiar kind of character study, but, again, one that never seems to dry up. The Debt of Maximillian doesn’t elevate its linage or add anything new, but it manages to go through the motions without sullying the reputation of its lead archetype.

"…a familiar kind of character study, but, again, one that never seems to dry up."