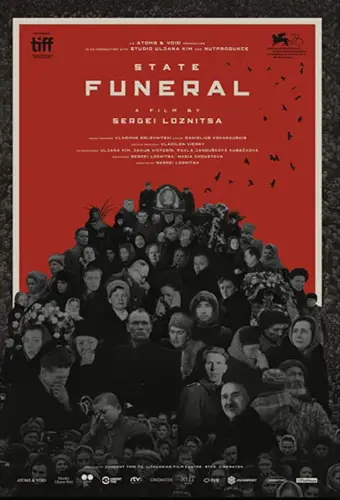

“The heart of the wise leader of The Communist Party and the Soviet People has stopped beating.” That is how Joseph Stalin’s death was officially announced to the Soviet citizenry in 1953 by way of loudspeakers scattered throughout the USSR. As an isolated statement, the declaration sounds empirical, precise, physiological, materialist and absent of any spirituality in keeping with the official atheism of The Communist Party. Writer-director Sergey Loznitsa’s documentary, State Funeral, makes it abundantly clear, however, that the USSR assembled a state religion around the man himself. The filmmaker compiles archival footage of grief-stricken masses from Moscow to Vladivostok and all the small villages nestled within the Soviet Republic.

The film emerges as a compelling historical artifact that gives undeniable proof that the Soviet Union practiced state rituals, produced a specific theology, and created a society of the spectacle that orbited around its sun, its quasi-God, Joseph Stalin. The government-approved script emanating from loudspeakers sounds as if heaven’s official secretary were giving the Soviet masses an account of the passage of Stalin from the material world into an immortal realm. They declare that while Stalin was alive, “he was everywhere.”

“…compiles archival footage of grief-stricken masses from Moscow to Vladivostok…”

And indeed, while alive, he was everywhere — portraits of Stalin gazed upon all Soviet citizens as his informant apparatus kept track of any dissent. The ubiquity of the picture made him a sort of Eastern Orthodox icon well before his death. After his heart stopped, the loudspeakers declared, “his head lies on a pillow, but there is no death here… there’s eternal life, immortality…he is with us, in every deed.” In short, he ascended and now gazes down on everyone, smiling as his revolution unfolds in the direction of its inevitable resolution.

As if this national spectacle were not sufficiently saturated with connotations of a state religion, banners and paintings of Stalin carried by crying mourners hammer the point home. These iconic images seem endowed with a sort of “livingness,” as if they have acquired special powers. One of the most powerful scenes portrays a group of sketch artists and sculptors surrounding Stalin’s open casket as they try to capture the likeness of the deceased leader. They attempt the most faithful renditions possible of the mortal body left behind by the “saint.”

"…what we do not see, but we know all too well exists, are the wincing faces of the tortured and murdered."