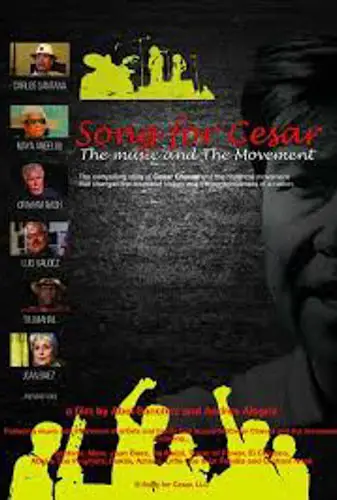

Cesar Chavez’s significance to the labor movement, activism, and Latin American history surpasses any singular book or film. But, with monumental figures such as Chavez, there is always a risk of edification to the point of no return wherein the figure becomes one-dimensional, an object, a statue. The documentary, A Song for Cesar, attempts to recast Chavez as a transcendent historical figure and an ordinary individual. Co-directors Andres Alegria and Abel Sanchez successfully achieve this balance by making viewers aware of the role of art in shaping Chavez’s personal life, and the role artists played in the United Farm Workers and The Campesino Movement’s demands for dignity and fair wages.

As with any activist or collectivist movement, it takes the effort of the many to bring about change. As one interviewee poetically puts it, “Beware of a movement that sings.” Chavez attracted the likes of Carlos Santana, Joan Baez, Taj Mahal, Los Lobos, War, as well as numerous dramatists, muralists, and poets. His speeches and rallies were often coupled with concerts, poetry readings, and even agitprop theater. In addition, we learn that the younger Chavez was a fan of jazz, as his granddaughter recalls how he had a written list of jazz albums he wanted. When he found a specific album at a record store, he would meticulously scratch it off his list. Stories like these humanize Chavez and make the film less an exercise in stilted history and more of an entertaining historical narrative with a musical heartbeat.

“…the role of art in shaping Chavez’s personal life, and the role artists played in the United Farm Workers…”

This is not to say that A Song for Cesar doesn’t expand its scope and cover the more significant labor issues going on in California in the 1960s and 70s. We are taken back to the grape boycott spearheaded by Chavez. We are enlightened to learn of the role played by Filipino laborers in the UFW’s efforts. We are reminded of the brutal treatment of Mexican braceros and farmworkers in the form of low wages, racism, degradation, child labor, exposure to dangerous pesticides, and physical violence originating from police and anti-union goons.

Chavez was a firm believer in non-violence. In theory, the aesthetic of non-violence in the face of injustice is inspiring. In practice, the brutality of violence upon one’s body without resorting to reciprocating that violence is far from being aesthetically pleasing. But this is precisely the subtext the film operates in. The music and visual arts behind the movement gave strikers the spiritual strength and motivation that helped them bear the pain and humiliation inflicted by goons. Chavez and the arts inspired by the movement gave strikers a sense of pride and identity.

Labor movements and activism are a mix of the Apollonian and Dionysian, of the individual and the collective, of the rational mind and the frenzy of the emotions. The strategic rationality was provided by Chavez and several others in the Campesino Movement. The emotional spark was provided by the many artists that were part of the Movement. Songs, murals, and poems gave strikers the emotional voltage capable of overcoming what seemed like insurmountable obstacles. As an artist in A Song for Cesar declares: “You cannot oppress people who are not afraid anymore.” In this country, we are currently witnessing nascent unionization movements from Amazon warehouses to Starbucks locations. We can only hope that the veil of fear that has long obscured the vision of American labor is replaced by the results produced by solidarity — courage and dignity.

"…Songs, murals, and poems gave strikers the emotional voltage capable of overcoming what seemed like insurmountable obstacles."