There have been over 180 school shootings in America since 2009. According to CNN, the U.S. has had “57 times as many school shootings as the other major industrialized nations combined.” Those are insane, highly discouraging statistics that reveal the state of this nation, steeped in abuse, violence, and authoritarian disregard.

Several prominent filmmakers have bravely ventured into examining the roots of this tragic phenomenon. Gus van Sant‘s Elephant cast an effectively dispassionate look at a school shooting by following the perpetrators’ daily routine. Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin assumed the perspective of the helpless mother, struggling to understand her child’s metamorphosis. Then there are Shawn Ku’s touching Beautiful Boy, Brady Corbet’s misguided Vox Lux, and Jason Buxton’s earnest Blackbird, all of which add their dramatic spin on these unimaginable horrors. Tucia Lyman’s latest addition to this small cinematic pantheon, M.O.M. (Mothers of Monsters), marks a powerful debut from a talented artist, and an unexpectedly incisive, original, and poignant study of mental illness.

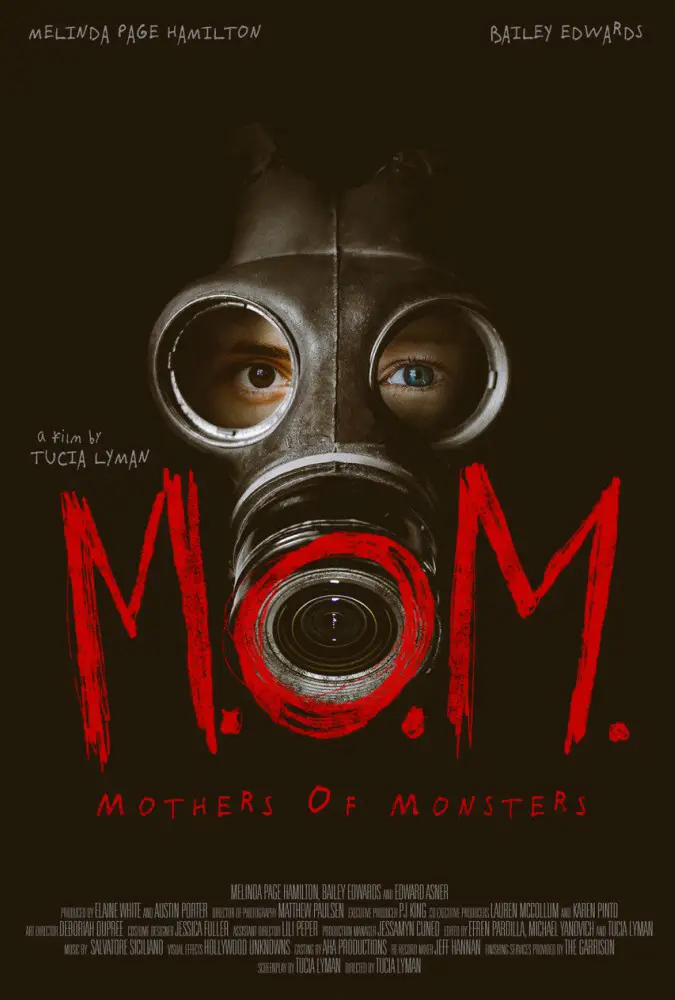

You really wouldn’t be able to tell this from the film’s cover art, nor its somewhat unfortunate title or tagline – all three of which suggest an all-out horror flick. Lyman wisely avoids resorting to gratuity, which would have been highly distasteful considering the delicate subject with which she’s dealing. Instead, she masterfully builds tension, flipping expectations at each turn, while getting under the skin and adding something new to the table. I felt my initial cynicism fading, gradually morphing into visceral terror.

“…composed of video snippets, played on a computer screen in random order by a mysterious observer.”

The entirety of M.O.M. is composed of video snippets, played on a computer screen in random order by a mysterious observer. This voyeuristic approach has been utilized before, sure, but in this case, it instantly creates a palpable sense of ambiguity and unease, as if we were a detective or psychiatrist attempting to piece together and provide a reason for a horrid occurrence. Again, bravo to Lyman for sustaining that level of immersion throughout the entire narrative.

“My name is Abbey,” the protagonist (Melinda Page Hamilton) states into the camera. “I am 42 years old. I’m a single mom. I think my 16-year-old son is a psychopath.” Indeed, Jacob (Bailey Edwards) has had violent tendencies since he was a child. Aside from his penchant for slaughtering animals and threats to rip his mother’s jaw off, he’s shown nonchalantly throwing a brick off a building (“Natural selection,” he states blankly), testing out electric dog collars and potentially shopping for guns. Not your average teenager.

One could even say it’s quite understandable why Abbey decides to “keep track of this s**t” by recording everything on camera. The authorities, after all, have refused to help her. “I don’t understand why there aren’t more resources to deal with this sort of thing,” Abbey says. She’s also doing it for other mothers, who believe their kid is a bad apple but love them anyway. Abbey suspects it’s all leading up to a planned school shooting.

"…Manifesting and examining every parent’s worst fear, bound to spark debate, this M.O.M. will pack some acid with your lunch."

Did anyone else watch this movie and think that it was going to turn out that it was the mother the whole time? Like the shoes part and he always said multiple times “I’m trying to protect you” ????

@Patience – I definitely did; I half expected him to produce video of her cutting up her own shoes or something. (I’m glad it didn’t go that route and stayed a bit more ambivalent.) I spent most of the movie asking myself “Is he or isn’t he?” and by the end I still wasn’t 100% sure (although I’m leaning towards yes based on his treatment of animals). But in my experience that is part of the pain of living with a psychopath: you don’t know for sure. Sometimes you feel certain and then they do something that throws you.