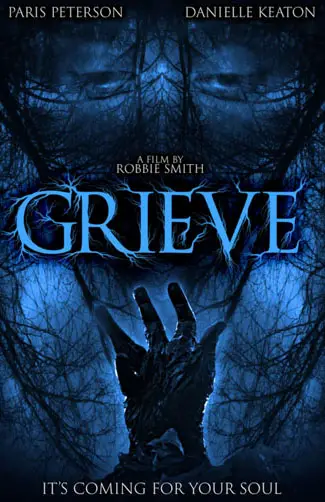

In a university lecture on traumatic life events in psychology, I was told that “you never grow up till you bury one of your parents.” While we see true horror on television during wartime, for many, it is harder to accept the death of one than of a thousand. The core of loss and how to grieve, which is personalized to each individual, comes to mind when watching Grieve, written by Dashiell Arkenstone and director Robbie Smith. This dramatic horror story is a thoughtful, moody meditation of one person entering the world of silent ghosts and the pain of the soul. It is oppressive from its opening shot of a large title and the lead lying on a floor, receiving bad news.

Sam (Paris Peterson) has lost Sarah (Danielle Keaton) to an accident and has become functionally useless. He mopes about, even with a sympathetic boss telling him to take time off. On his mother’s advice, he makes a trip to the family cabin. Once there, Sam thinks he can hear Sarah everywhere in the house and the woods. This leads him to believe he can commune with her soul. Later, Sam runs into his friend Ralph (Jacob Nichols) while buying beer. The two childhood friends catch up by popping pills and rocking out to loud metal music. Will this or contacting Sarah’s soul bring Sam back from the edge?

“…Sam thinks he can hear Sarah everywhere in the house and the woods.”

Grieve features long – very long – stretches of stillness. Motionless people or images, such as when Sam stares at a frozen dead rat on a fence, sit on screen for a while. There are also voice-overs in French, which might be the work of Baudelaire or prose by Proust. Creaky cabins, whispering voices, and the glimpse of a figure made of twigs and skulls move the atmosphere to doom.

The film also mixes folk horror with some brutally violent, almost sacrificial endings in the snow. This is a psychological tapestry of an odyssey that some may find unrelenting, like a piece of symphonic music with different movements. This is alluded to by Sarah, who was a pianist, and the extensive use of Chopin in the soundtrack.

The actors, especially Nichols, do well with the dialogue. His delivery is good and natural, and at times, he has an irresistible twinkle in his eye, making his performance genuine. He is a good foil for the laconic movements of Peterson’s Sam. Moments of horror involving ghosts, recrimination, and a descent into grief-stricken madness give Grieve a texture that fulfills without being overpowering. Grief is an individual trip, and this is a personal journey.

"…fulfills without being overpowering."