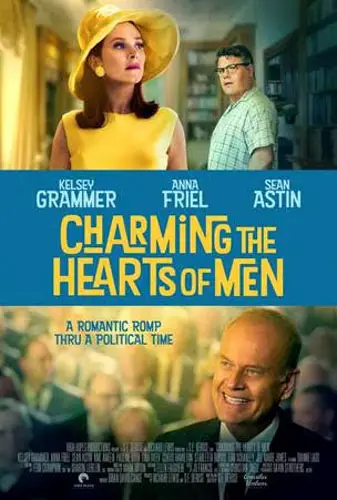

S.E. DeRose makes her cinematic debut with Charming the Hearts of Men, which she produced, wrote, and directed. The story begins in 1963 in the Deep South, with the funeral of a well-to-do judge and the return of his wayward twice-married daughter Grace (Anna Friel). The fiercely independent woman moves back to her lavish childhood home only to realize that her father was nearing bankruptcy, bleeding money in funding her worldly travels.

Unsure how to keep her home, in addition to her family’s staff, Mattie (Starletta DuPoi) and Jubilee (Pauline Dyer), Grace attempts to woo a Congressman (Kelsey Grammer). He just so happens to be in the throes of negotiating the landmark passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Moving through a series of subplots, including a sex worker Ruth (Tina Ivlev), who dreams of legitimizing herself with her daughter, and a pawn shop owner (Sean Astin) who helps out Grace, the drama encapsulates the racial and sexist tensions of an entire town during the 1960s.

While buoyed by lived-in performances from Friel and Grammer, Charming the Hearts of Men awkwardly places fictionalized characters at the precipice of major historical faultlines, positioning Grace’s cultural awakening as a central call to include the word ‘sex’ in the Civil Rights Act. DeRose competently constructs her first feature, balancing several tonal shifts and juggling more than a half-dozen supporting characters.

Unfortunately, she problematically conflates Grace’s plight to become self-sustainable in an ingrained patriarchal society with the struggles of the characters of color, suggesting a kinship between her attempts to maintain an upper-class (read: white) lifestyle and the civil rights movement. A number of scenes at a juke joint named the Blue Goose introduce the financially unstable Viola (Jill Marie Jones). The filmmaker teases a juxtaposition between Viola and Grace that she is either unwilling or simply cannot mine for thematic parallels. Instead, Viola, like several other characters, is frustratingly one-note, eventually reduced to antagonist before being redeemed by, of course, Grace.

“…Grace attempts to woo a Congressman…[who is] in the throes of negotiating the landmark passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.”

Grammer’s unnamed Congressman, seemingly a Democrat, is a cypher for the film’s overall whitewashed political stances, acts as a foil for Grace. Holding court at her father’s funeral before becoming a possible suitor that can allow Grace to escape her impoverishment, the Congressman traverses the state (Georgia?) with his driver Walter (Amel Ameen). Walter is at odds with Martin Luther King Jr’s movement, suggesting, in a truly odd scene that wears out its welcome, that those who follow King are going against America’s values.

This bi-lateral approach, which attempts to give all political viewpoints equal weight, oddly neuters any political overtones. In the process, a film about the passage of a landmark anti-discrimination bill becomes shockingly apolitical. (Spoilers ahead) By the end, when Grace finally convinces the Congressman to amend the bill and opens up a restaurant that, very literally, presents a utopian vision of the Deep South, in the 1960s, where everyone has a seat at the table, Charming the Hearts of Men has abandoned any semblance of realism in favor of harmonious fantasy.

This both-sidesism extends beyond DeRose’s fictional tale. Susan DeRose has made headlines as a restaurateur in Atlanta and made several disparaging comments against the Black Lives Matter movement. Additionally, she’s argued against the mere existence of systemic racism in the United States. Needless to say, DeRose’s troubling political viewpoints, unfortunately, bleed into the film’s idealized view of mid-century Southern race relations.

Despite the pedigree and performances, the overall political sentiments and underdeveloped script hold Charming the Hearts of Man back from presenting a fully realized portrait of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Instead, it reduces a landmark historical moment into a self-actualizing journey for a mild-mannered white woman. However, the film is still a potent reminder of the skills of the cast, especially Friel and Grammer, to elevate even the most pedestrian of projects.

"…buoyed by lived-in performances from Friel and Grammer..."

I was hoping for the Frasier of reviews, but you gave me Money Plane instead. The review started out fine, but somewhere down the line decided that everyone has to be 100% for or against every political movement in the United States, or everything they say and do will be called into question. This is idiotic and part of the reason that we need more stories like this and less reviewers this ignorant.