Critically, we also explore the social and/or economic conditions within which our disaster appears. What do these conditions look like as our story opens and how might they inform the protagonist’s motivation that will drive him or her (this being the disaster movie, it’s more often him rather than her, unfortunately) to take the lead in rescue efforts? Is there a wife or a child or children in peril? Is the protagonist an environ mentalist of some sort who might take an especially keen interest in cur tailing a potential environmental disaster? While I would contend that disaster movies aren’t necessarily, as Keane postulates, “borne out of times of crisis” (5), I would agree with him in the sense that movies, like much of art regardless of the genre, are typically reflective of the times in which they are produced (5). These intrinsic circumstances contribute to what type of disaster the characters might experience and who might be the person or persons that make it out alive.

“Act Two: All Hell Breaks Loose” serves as the crux of the story and, arguably, the overarching reason that moviegoers buy their tickets to disaster films in the first place: it’s when, as they say, s**t gets real. The key spectacular set piece, the typical harbinger of the beginning of Act Two, however it is conveyed, is revealed to delighted awe from the audience. Depending upon whether we are watching a movie with a proactive or a reactive narrative thrust (both instances of which will be explored in Act Two), the disaster will occur and the core group of survivors will then struggle to get to safety or the disaster will be ongoing and the characters will use every ounce of wit and ingenuity at their disposal to prevent fur ther peril. Regardless, in Act Two, the crisis mounts and reaches a fever pitch while characters expose their true natures (for better or for worse), and the movie mostly uncovers which stars will and which stars won’t sur vive the disaster.

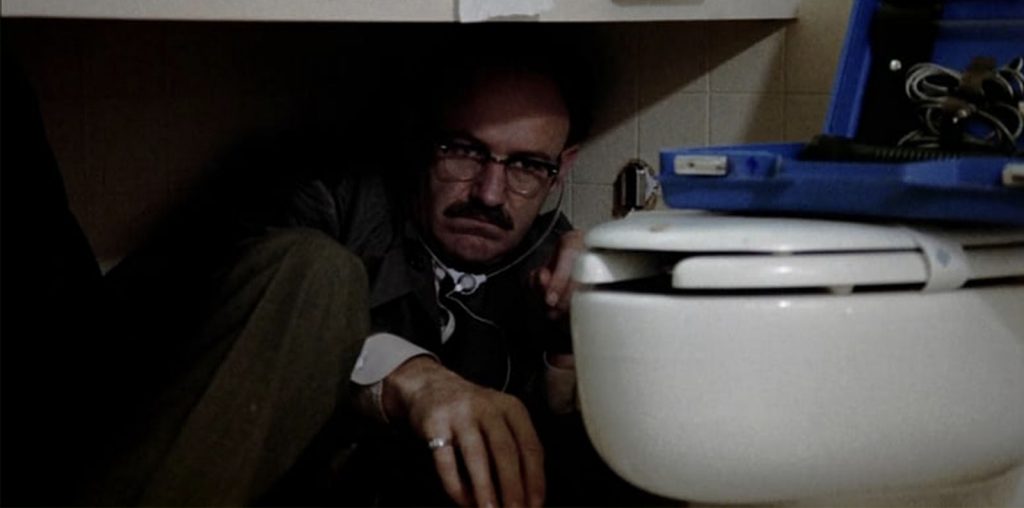

“Act Three: Out of the Woods?” is, I admit, a bit of a misnomer. This is because in a disaster movie, one is never truly out of the woods. Rather, one experiences a decline in severity of the disaster-for the time being, at least. Following the occurrence of the disaster, which we refer to as the Primary Disaster, there is always a trail of death and destruction left in its wake that those who have withstood the event must weather. To that end, in this section of the book we explore the concept of the Law of the Second Disaster that is present in most movies of this type. After all, disaster movies are intended to be a spectacularly thrilling form of mass entertainment, not a cheap one-and-done cash grab (though some might argue that a fair share of entertainment spectaculars do, unfortunately, deserve this ignominious label). Therefore, the audience must be provided with one final “WOW” to not only send them smiling into the night, but also to justify increasingly exorbitant ticket prices (whether in theater or streaming), not to mention the various and pricey accouterments that are part and parcel of the moviegoing experience (popcorn, soda, candy, etc.). But as with most dramatic art and in keeping with the customary beginning-middle-end narrative composition (Bordwell et al. 68), Act Three is when the story strands are (hopefully) wrapped up and conflicts are (hopefully) resolved. Thus, we explore the generic probabilities of, and reasons for, character survival.

“…because in a disaster movie, one is never truly out of the woods. Rather, one experiences a decline in severity of the disaster-for the time being, at least.”

Additionally, we take a look at the Preamble (better understood as the Prologue) and Epilogue or Coda, narrative mechanisms with which many disaster film creators choose to open and close their stories. More prevalent in recent iterations of the disaster film than in earlier creations, the Preamble and Epilogue/Coda serve as ways to, respectively, psych up the audience prior to the onset of the story proper with an opening spectacle to juice their adrenaline, and, later on, as a look into the future after the disaster has decimated the story world and forced a restructuring of society.

Throughout the explorations of the various elements of the disaster film, however, Are We Living in a Disaster Movie? will never lose focus on the actual disaster that is happening, in real time, as we speak. You will see the ways in which each act in this book corresponds to specific narrative beats that have been achieved in the Covid-19 pandemic disaster. By placing a discussion of the disaster film subgenre within the context of a contemporaneous, real-life disaster, the deconstruction of the disaster film will become palpable, and a more focused generic picture will come into view for audiences who aren’t quite sure what to make of the current predicament.

In the chapters that follow we examine how the blueprint of the real-world disaster film we are living in has conceivably already been writ ten by Hollywood disaster films going back decades. With this generic template in mind, we perhaps might be able to uncover the map to our future.

Get the book is available from all the popular booksellers and the official McFarland Books website so you can continue to read Are We Living in a Disaster Movie?: How Genre Conventions Predict the Plot of the Covid-19 Pandemic.