Disaster in film can be traced almost as far back as the advent of the motion picture itself, though the term “disaster film” wasn’t explicitly used until the 1930s (Keane 13). More than one hundred years ago, for example, Edwin S. Porter’s seven-minute short Life of an American Fire man (1903) silently documented the titular hero as he responded to a residential blaze. As the film industry matured, so did the disaster film. With D.W. Griffith shepherding the modern-day epic film onto cinema screens with the one-two punch of The Birth of a Nation (1915) followed by Intolerance (1916), as well as the introduction of sound film technology in the 1920s, the stakes grew ever higher for studios to produce more elaborate and awe-inspiring pictures and spectacles, in order to entice ticket buyers.

In his essay “The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde,” theorist Torn Gunning defines what he refers to as a “cinema of attractions,” which “directly solicits spectator attention, incit ing visual curiosity, and supplying pleasure through an exciting specta cle-a unique event, whether fictional or documentary, that is of interest in itself” (“Cinema of Attractions” 73). Gunning’s definition is as apt and accurate a raison d’etre for the disaster film as one is likely to find, and it will be referred to liberally in this book.

On a particularly rudimentary level, as the movie industry entered into what some might define as the Golden Age of Hollywood, studio executives now began to realize the need to include the spectacular element in their pictures for their product to become more elaborate, more dazzling pieces of entertainment. In one regard, large-scale sweeping epics such as Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939) or superior technical achievements such as The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939) delivered the necessary spectacle. But as their filmmaker impresario kin would copycat years down the road, the studio powers that be also looked to disaster, and in particular natural disaster, as a means of procuring the spectacle. In fact, the 1930s saw a mini genre cycle of natural disaster films emerge, including the tsunami extravaganza Deluge (Felix E. Feist, 1933), San Francisco (W.S. Van D**e, 1936), which showcased the 1906 California earthquake, and In Old Chicago (Henry King, 1938), which reimagined certain events surrounding the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

As decades passed and movies evolved both in economy, scale, and creativity, cinematic disasters became more involved and the spectacles that were offered to audiences became more vivid and eye-popping. More bang for more buck, if you will. Significantly, however, the noticeable commonalities present in the narratives of disaster films were becoming more identifiable. If genre can be envisaged in an academic sense as more or less a taxonomic system of grouping movies that contain similar tangible traits, one could then ask his or herself, as professor and film scholar Stephen Keane articulates in his book Disaster Movies: The Cinema of Catastrophe, not how “such and such a film is a disaster movie, for exam ple, but rather asking what are the properties that might go towards identifying a film as a disaster movie” (3).

In his foundational essay “The Bug in the Rug,” Maurice Yacowar identifies eight overarching “types” of disaster film: Natural Attack, The Ship of Fools, The City Fails, The Monster, Survival, War, The Historical, and The Comic (335-41). Recalling Yacowar and depending upon which criteria one uses to define a disaster movie, products as diverse as the Titanic dramatization A Night to Remember (Roy Ward Baker, 1958), the gooey B-movie The Blob (Irvin S. Yeaworth, Jr., 1958), the seminal zom bie classic Night of the Living Dead (George A. Romero, 1968), or even the mother of all monster movies Godzilla (Ishiro Honda, 1954), might qualify as mid-century disaster pics.

Inarguably, the disaster genre, as most people nowadays popularly apprehend it, reached its pinnacle of mainstream visibility in the extraordinarily successful cycle of films released in the 1970s, beginning with George Seaton’s Airport in 1970. Based upon the popular novel by Arthur Hailey, Airport employed a star-studded cast including Dean Mar tin, Burt Lancaster, Jacqueline Bisset, Jean Seberg, George Kennedy, and Helen Hayes, along with pulpy melodrama and on-the-ground as well as in-the-air disasters. In utilizing this formula of an all-star cast, plus disaster, plus melodrama, disaster movies achieved massive profitability and renown in theaters across the country as America entered the Me Decade.

Airport was produced on a budget of $10 million in 1969 and released the following year to the tune of a worldwide gross of more than $100 mil lion (“Airport-Cast I IMDbPro”). When we translate that picture’s haul to 2021 dollars, Airport’s budget would amount to roughly $74.4 million, and its worldwide gross would balloon to more than an astounding $707 mil lion (“Inflation Calculator”). With that kind of monetary take, it is crystal clear why and how Airport would have incentivized those with green lighting power behind an entire industry to develop and release their own cinematic output utilizing the template provided by Airport, and, in the process, pretty much birthing the disaster genre as we contemporarily reference it.

In the wake of the tremendous success of Airport, the disaster genre took flight and proved a popular draw for audiences throughout the 1970s. Two years after the release of Airport, The Poseidon Adventure (Ronald Neame, 1972) was released, followed soon thereafter by two other founding members of the disaster film canon: The Towering Inferno (John Guillermin, 1974) and Earthquake (Mark Robson, 1974). All manners of disasters were exploited in the 1970s ranging from natural, such as Earthquake and Avalanche (Corey Allen, 1978), to the technological, Westworld (Michael Crichton, 1973), and even to outer space, as in Meteor (Ronald Neame, 1979). Most notably, the massive success of Airport spawned a smash series of air-bound disaster movies released throughout the decade, including its immediate sequel Airport 1975, as well as the water-bound Airport ’77 (Jerry Jameson, 1977) and the series’ inadvertent parody, The Concorde…. Airport ’79 (David Lowell Rich, 1979).

“…the disaster film has persevered and adapted as filmmakers continue to up the apocalyptic ante, whether in the scope of their narratives or in (or sometimes in addition to) the technologies that allow them to realize their spectacles.”

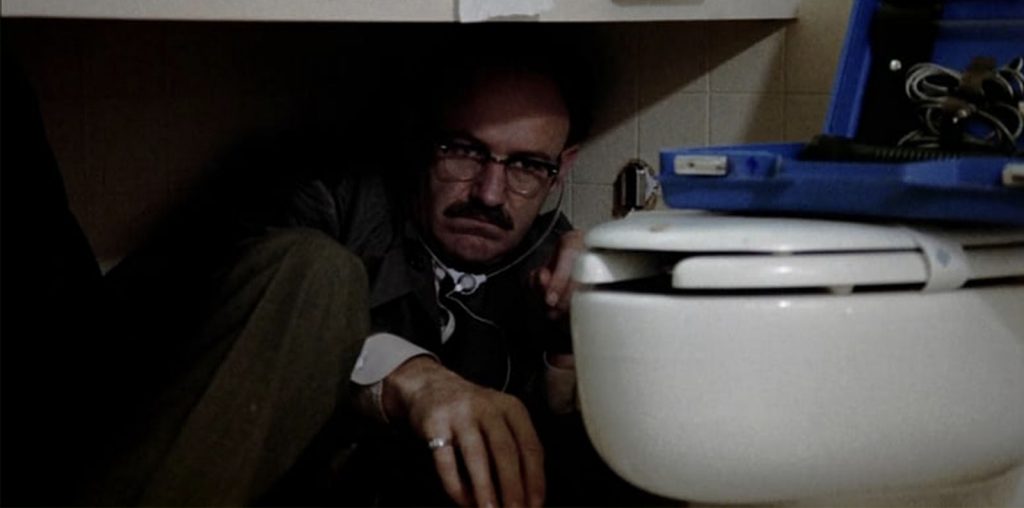

As the 1970s drew to a close, the disaster genre weakened in distinction, both critically and economically. As a matter of example, we have only to look at the clanging death knell of the 1970s disaster movie, the odious When Time Ran Out … (James Goldstone, 1980) and the pointless sequel Beyond the Poseidon Adventure (Irwin Allen, 1979), which, in my opinion, can’t even be justified as a disaster movie. (This is primarily due to the fact that the entire movie is predicated on a disaster that already occurred, in the earlier, and much better, The Poseidon Adventure; there is no new disaster to be thwarted. A collapsed ventilator is hardly on a disas ter par with the capsized cruise ship.) The decline in cinematic quality of product in the latter years of the 1970s was no doubt due in part to media overexposure of the genre, which had now become a parody of itself. Steve Neale quotes Thomas Schatz’s theory of “generic development”: “Finally, once ‘the genre’s straightforward message has “saturated” the audience… a genre’s classic conventions are refined and eventually parodied and subverted…”‘ (qtd. in Neale 211-12). Indeed, the riotous spoof that mocked the entire Airport series, Airplane! (Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, 1980), can, more or less, be regarded as the de facto film which ter minally punctuated the popularity of the 1970s disaster cycle.

Movies in the disaster vein would sporadically turn up in the 1980s and early 1990s, including the capstone film in mega-producer Irwin Allen’s feature arsenal When Time Ran Out … and Chuck Russell’s 1988 remake of The Blob. But the next official disaster movie genre cycle did not occur until the mid to late 1990s, conceivably beginning with Jan de Bont’s Speed (1994). This end-of-millennium disaster cycle included a close cousin to The Sibylline Scourge, 1995’s Outbreak as well as the alien invasion epic Independence Day (Roland Emmerich, 1996), cyclone smash Twister (Jan de Bont, 1996), and the twin volcanic eruption movies of 1997, Dante’s Peak (Roger Donaldson, 1997) and Volcano (Mick Jackson, 1997). This cycle also contained the competing asteroid-hurtling-towards-earth extravaganzas Deep Impact (Mimi Leder, 1998) and Armageddon (Michael Bay, 1998) as well as Emmerich’s own reimagining of Godzilla (1998).

Throughout the early aughts and continuing right up until the pres nt, the spectacles continued to grow in both size and impression. Since the dawn of the new millennium, filmmakers have treated audiences to gigantic doomsday pieces such as The Day After Tomorrow (Roland Emmerich, 2004) and 2012 (Roland Emmerich, 2009) (gee, maybe it was just one guy!), monstrous monster movies including Peter Jackson’s interpretation of King Kong in 2005 as well as yet another version of Godzilla (Gareth Edwards, 2014), historical disaster spectaculars such as Pom peii (Paul W.S. Anderson, 2014), apocalyptic zombie scenarios such as 28 Days Later… (Danny Boyle, 2002) and World War Z (Marc Forster, 2013), updated natural disasters including San Andreas (Brad Peyton, 2015) and Geostorm (Dean Devlin, 2017), biological disasters such as Contagion (Ste ven Soderbergh, 2011), and proving Schatz’s genre theory, the disaster send-up Sharknado (Anthony C. Ferrante, 2013) and its offspring.

Throughout the decades, the disaster film has persevered and adapted as filmmakers continue to up the apocalyptic ante, whether in the scope of their narratives or in (or sometimes in addition to) the technologies that allow them to realize their spectacles. But amidst the decades of massive hits and disastrous flops, visual spectaculars and lackluster wannabes, the fundamental stories and the generic tropes have largely remained the same. Allowing for reasonable overlap and variation, Yacowar uncovers several generic conventions that appear to be inherent in disaster films, such as the cross-section of society as illustrated by the cast, the bonding of a set of characters in the face of calamity, and the inevitable romantic subplot (342-50).

In this book we will refer to the common tropes of the disaster film as well as identify and explore others. During the course of our discussions, however, it will become clear how particular disaster subgenre conventions can be assigned without hesitation to the current Covid-19 disas ter epic we have all been living through for the past few years. In addition to some of the conventions that Yacowar recognizes, we will explore, for example, the role of the female lead in relation to the male lead, the death of the Poignant Character, and whether or not a certain movie exhibits a more proactive or more reactive behavior in its confrontation of said disaster. Adhering to the paradigm of a progressive beginning-middle-end composition that serves much of dramatic filmmaking (Bordwell et al. 68), it is possible to illustrate the application of disaster genre conventions to the Covid-19 timeline and to parallel when certain real world narrative benchmarks are reached. With this in mind, we will refer to the beginning portion of our examination as Act One: The Buildup, the middle as Act Two: All Hell Breaks Loose, and the concluding section as Act Three: Out of the Woods?

“Act One: The Buildup” addresses the initial stages of the disaster scenario and what components are generally found to be present therein. In the portion of a story prior to the cataclysm that will follow, we should be able to identify with confidence who the main players are, and, barring any eleventh-hour surprises, what their relationships are to one another. Who is likely to be our Poignant Character, the individual who will meet an especially melodramatic demise? Are there kids involved? If so, what are their specific child-centric attributes that could prove vital much later in the story? If we see genre as a means of classification and if we are aware of the conventions that surround the majority of disaster films, we can project our assumptions about character, plot, motivation, etc., onto the characters as we meet them and the situations as we encounter them.