However, there was a mystifying darkness approaching from far away that would soon entwine itself into the global population and catch every one off guard. You see, buried beneath the blustery political lead stories in newspapers and across digital media outlets, items concerning a curious occurrence across the Pacific Ocean in China were being published. An alien, never-before-observed flu-like illness was affecting people in the Asian nation’s Wuhan region.

The reporting of a suspected outbreak of a mysterious illness was, on its face, seriously troubling but not entirely novel. The early 1980s cover age of what would come to be known as the AIDS epidemic, for example, involved news outlets describing the puzzling deaths among homosexual men in New York City and San Francisco that were apparently caused by a particularly lethal strain of cancer. “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” read the headline of an article in the July 3, 1981, New York Times (Blake more), the first mainstream news outlet to cover the story.

Yet, the perceived irrelevance of the New York Times story is evident in the article’s location in the newspaper and in its placement on the page. The article appeared in Section A, page 20 of the July 3, 1981, edition in a narrow, almost insignificant column to the left of a more attention-grabbing, almost full-page advertisement for Independence Savings Bank (Altman). This out-of-the-way situation in the newspaper foreshadows the initial coverage of the novel coronavirus, an early article concerning which, similarly, would be published in The New York Times on January 7, 2020, in Section A, page 13 (Wee and Wang). Hardly what one would refer to as front-page news.

Now, it is natural to expect a healthy amount of guarded trepidation when a person is made aware, either through media channels or other means, of a strange sickness that has surfaced overseas. Who wouldn’t at least raise an eyebrow? But the sense of foreboding was magnified in mid January 2020, when John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City (JFK), San Francisco International Airport (SFO), and Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) all implemented ominously heightened security measures directed at passengers arriving in the U.S. from the afflicted Chinese region (“Public Health Screening”). A troublesome scenario was beginning to take shape: if whatever this illness was could not be contained and eradicated quickly, a disaster of global proportions was not necessarily outside the realm of possibility.

Sometimes it bears reminding that human beings are earthbound creatures, members of the animal kingdom in the same way that dogs, cats, or chimpanzees are. There are illnesses existent in nature that will, like a food we don’t much like the taste of, cause our senses to recoil and instruct our immune systems to react in such a way as to eliminate the particular offense from our bodies. Oftentimes, a couple of sneezes, some time in bed, and chicken soup will do the trick. However, there are some pathogens prevailing in the natural world that will prove poisonous to human beings and that cause conditions our highly evolved and advanced immune systems have only minimal tools to combat, such as Ebola or many forms of cancer.

So as the 2019-20 winter season entered its most unforgiving leg in those first few months of the new year, frightening developments in relation to this mysterious illness continued to ensue. On February 5, barely one month after that early article in The New York Times appeared, more than three thousand six hundred vacationing passengers aboard the lux ury cruise ship Diamond Princess were forced to quarantine onboard following an outbreak of what the world would come to know as Covid-19. Not long afterward, on February 7, Dr. Li Wenliang, a Chinese physician later to be renowned as the retroactive whistleblower who had attempted to warn the world about the conceivability of widespread infections were the outbreak not contained in China, passed away from its effects (Taylor). A snowball effect was strengthening; the sense of looming disaster was now inescapable.

“The formal design of the disaster movie can arguably be construed as a subgeneric form of the standard action-adventure genre…”

Across the Atlantic Ocean in Europe, Italy issued lockdown orders on February 23 for towns in its northern Lombardy region as positive tests for this novel coronavirus cropped up in the area. As though this progression was now imitating a particularly sick game of global whack-a-mole, reports of infections popped up in nations around the world as the virus spread internationally; both Iran and Brazil were soon identified as hot beds of virus activity (Taylor).

Then, on February 29, for those of us in the States watching helplessly as this enigmatic sickness engulfed the globe like an errant oil spill, the unthinkable yet inevitable happened: it was announced that the United States had reported what was believed to be its first coronavirus death, a man in Washington State (Taylor). A few days later, on March 3, 2020, a case was confirmed in New Rochelle, New York, a suburb located in the New York City metropolitan area, the most populous metro in the United States (Lombardi). The disaster had landed. If these genuine occurrences were written in the narrative of a mainstream Hollywood disaster movie, the arrival of the virus in New York City would be right on schedule. Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you, The Sibylline Scourge.

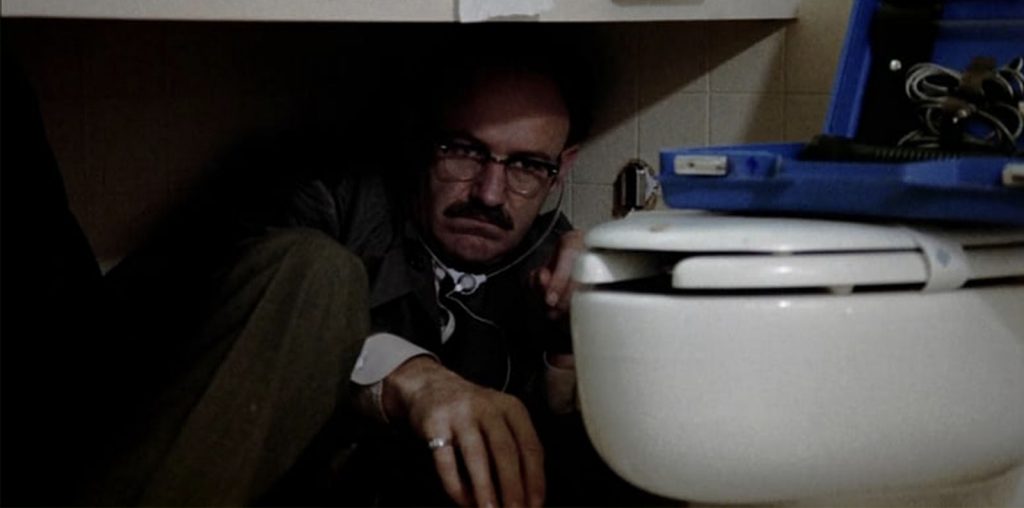

A genre as evergreen to the cinema as the Lumiere Brothers, the disaster film is a thrilling piece of entertainment particularly suited to and comprised of the cross-pollination of more salient dramatic tropes. The formal design of the disaster movie can arguably be construed as a subgeneric form of the standard action-adventure genre, seeing as how within the basic chemistry of disaster stories there exists the race against time to survive a catastrophic event. However, in most disaster films one will find elements of romance or melodrama as in Airport 1975 (Jack Srnight, 1974), which really lays it on thick, or in Titanic (James Cameron, 1997), with its Rose/Jack storyline. Perhaps the element of the thriller might be more prominent in film, such as in Outbreak (Wolfgang Petersen, 1995), or maybe even comedy, whether intentional or unintentional, like in Snakes on a Plane (David R. Ellis, 2006), for example.