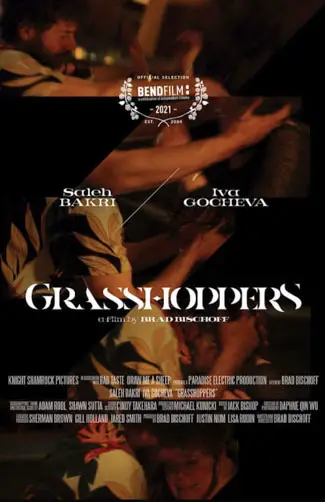

Brad Bischoff’s subdued drama Grasshoppers leaves a lasting impression, certain images glowing like embers somewhere in the depths of the viewer’s mind long after the credits roll. Simplicity is key: the filmmaker does not rely on stylistic flourishes or scandalous drama to propel the narrative forward. It’s the words that are spoken, what is left unsaid, the turbulent relationship between the relatable, hapless leads, and the themes being explored that keeps one glued to the screen. The wintery setting and prevailing atmosphere of hopelessness may not exactly be welcoming, yet once one surrenders to the film’s somewhat meandering rhythm, it becomes impossible to look away.

Star-crossed immigrant lovers Nijm (Saleh Bakri) and Irina (Iva Gocheva) wake up in a luxurious mansion in a gated community. The place – clearly not theirs – seems abandoned. “Everybody is gone for the winter, even the animals,” Nijm states as they stroll through the upscale, mostly empty neighborhood. “A vacation spot for the wealthy.” He has a crazy idea: to stop in every house for a drink, to see who has the best one. They have drinks at the bar before they start, and continue to drink relentlessly throughout the rest of the feature.

Turns out, not everyone left for the winter. When they visit an open house, a skeptical realtor greets them, along with some potential buyers. Soon after, our heroes are caught having sex in the bathroom. In another home, a subtly condescending neighbor offers Nijm a job. “He’s not gonna give me s**t,” Nijm declares. “I’ve got my own thing coming… He likes me as a quota for his company.”

The couple delves deep into discussions about family, career, and infidelity, their speech becoming slurry as they consume more booze. Things are gradually revealed. Nijm harbors dreams of being an actor; Irina’s continuous nausea may be caused by pregnancy; their actual occupations are divulged. Towards the finale of Grasshoppers, the two are wasted, stumbling into a restaurant, attempting to assemble their scattered, melancholic thoughts into coherent declarations.

“…has a crazy idea: to stop in every house for a drink, to see who has the best one.”

Daphne Qin Wu’s splendid cinematography reflects the protagonists’ state of mind. Serene and painterly at first, depicting frozen ponds and overcast skies with dark clouds threatening to burst, it soon becomes jittery, unstable, swaying as if the camera itself were intoxicated. The two leads are impeccable, their chemistry electric, their sorrows and ambitions abundantly clear. There’s a very real tenderness to their complicated relationship. “Do you see yourself as a father?” she asks. “Someday for sure,” he replies, “but today, I love you.” Wu’s close-up shots leave them no room to hide, and the actors showcase raw emotion, sometimes sweltering, sometimes understated.

Bischoff’s eye for detail is remarkable. Throughout Grasshoppers, seemingly inconsequential things cause ripple effects: a possum in a black trash bag, a detrimental sip of alcohol, Nijm’s inability to perform sexually in an empty bar, an attempt to secure a table at an upscale restaurant. “I’m sick of having just enough,” he says. “For once, I want that steak at the table.” “You’d make a horrible father,” she tells him at one point, her words like a stab to the heart – yet she doesn’t mean to offend. She’s just telling the truth.

The filmmaker maintains a deliberate pace, wherein his themes are crystallized, unencumbered by exposition or forced plot mechanics. Bischoff covers it all gracefully: the futile search for the American Dream, class disparity, planning one’s life, facets of love, a sense of entitlement, feeling like the world owes you, and being an outcast. He doesn’t paint in black and white. His heroes aren’t lovable necessarily, nor are they detestable. They’re just human, failing and striving and f*****g up. Nor does he condemn, although he does poke fun at, the top 1% (the similarity in the houses’ architecture accentuates the mindset of the elite).

We’re all grasshoppers in a way, jumping from one stage of life to another, just trying to make something of ourselves, to love, eat good food, and be happy. Whether Nijm and Irina find their happiness remains to be seen. But the final shot sure leaves you hoping.

"…Bischoff’s eye for detail is remarkable."