“How can you reconstruct a man,” director Rupert Murray asks in thoughtful voiceover, “from events distorted by the camera and the man behind it?” Murray tries to answer that thorny question in “Unknown White Male,” an irritating documentary that fails its fascinating subject matter.

Murray’s subject is Doug Bruce, a British thirtysomething living in New York City. On July 3, 2003, Bruce suddenly fell victim to a rare and untreatable mental ailment that erased virtually his entire memory. Because he had wandered from home without ID while he was in the “fugue state” that precedes catastrophic memory loss, Bruce turned himself into police, unable to provide his name or any details about himself.

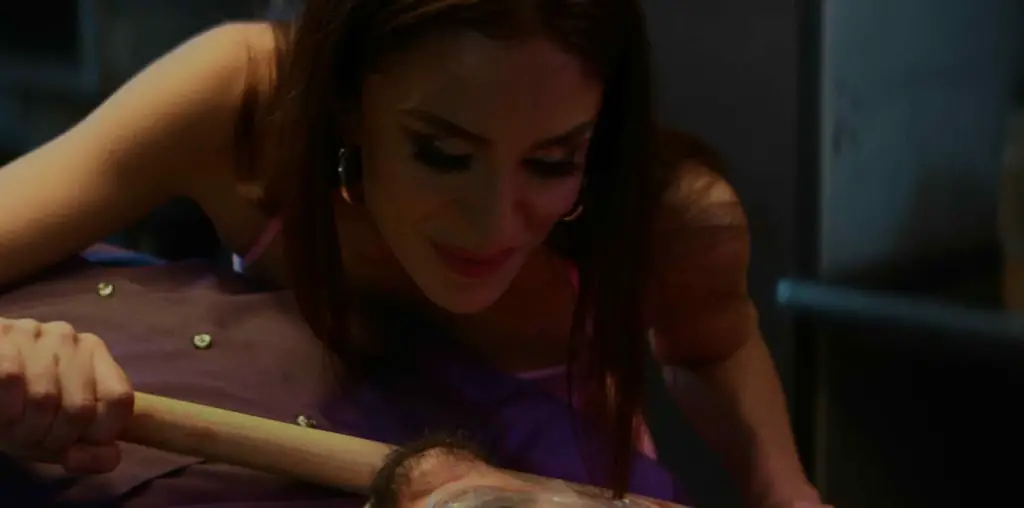

“Unknown White Male” dramatizes the panic of those first days, then tracks the bizarre process by which Bruce slowly reintroduced himself to his own life.

Murray had been friends with Bruce prior to the memory loss, so when he heard what had happened, he did what any friend would do — he asked his stricken comrade for permission to make a documentary about the strange situation. “Unknown White Male” is one of those nonfiction pictures that smacks of exploitation, because it’s not as if Murray stumbled onto a great story; he flew from Europe to America in search of one.

A fair amount of the picture comprises footage Murray shot once he reconnected with Bruce some time after the memory loss; other elements include Bruce’s own video diaries and archival elements such as childhood photos.

Although the predicament seems a natural for exploration — the idea of suddenly losing all recollection of one’s emotional and intellectual life is horrifying — Murray can’t quite decide what picture he’s making. “Unknown White Male” is neither serious nor clinical enough to provide an authoritative look at Bruce’s condition, and it lacks the depth to function as a tribute to the personality that disappeared when Bruce’s brain was afflicted. The movie occupies a middling terrain between personal cinema and objective journalism.

It also suffers because of Murray’s undisciplined visual style. He overuses fisheye lenses to the point of amateurism in sequences meant to replicate Bruce’s confused state, he relies on pointless montages of insignificant images, and he even stops the movie cold to present parts of a vapid short film he made in the 1980s, ostensibly because Bruce is featured in a few shots.

Murray’s most egregious offense relates to his own appearance in the documentary. The director tapes himself arriving at Bruce’s loft, and we’re actually subjected to repeated angles of Murray’s neck while he holds the camera in one hand and handles luggage with the other. It’s hard to say if these scenes made the final cut because Murray had no other options or because he succumbed to narcissism.

Either way, the viewer is the loser in this equation.

The biggest disappointment, however, is that “Unknown White Male” should have been gripping. Bruce’s situation is unusual, frightening, and philosophically provocative. But Murray gets distracted by needless visual detours, and he fails to make his subject sympathetic. Bruce comes across as a handsome, independently wealthy snob who possessed extraordinary resources and actually embraced the opportunity to remake himself.

It’s quite an accomplishment to turn a deeply personal story about loss and pain into a droning clunker, but that’s what Murray has done. The good thing is that the real story seeps through, despite Murray’s tendency to obscure the humanity of this tale behind layers of artifice and minutiae.