There are two Sally Fields in “Two Weeks,” both as Anita Bergman of North Carolina. There’s the Sally Field we know sight unseen, being recorded and interviewed by her son Keith (Ben Chaplin), talking about when she gave birth to him. She looks healthy, long before the cancer has set in. The other Sally Field is without the benefit of setting herself up for posterity on camera, gravely sick in bed, puking, and weakly trying to walk. The cancer has gotten her, eating her, taking away everything she is.

But before she leaves herself for good, her children arrive. Keith, a film director in Hollywood (writer/director Steve Stockman putting himself in the film in a fictional manner, as all this is based on his own experiences of his mother’s death with his siblings), is greeted at the airport by his sister Emily (Julianne Nicholson, and if you’ve not seen the other films she’s in or watched her on “Law & Order: Criminal Intent,” please start), who’s getting through this by a number of self-help books in her car, and continually referencing one, especially in a devastating scene where Anita is extremely pained in bed on her watch and, not knowing what to say or how to help, Emily references one of the pages she’s marked off in her book. She’s not the sort who only knows life through books, but this is how she knows how to deal with all of this.

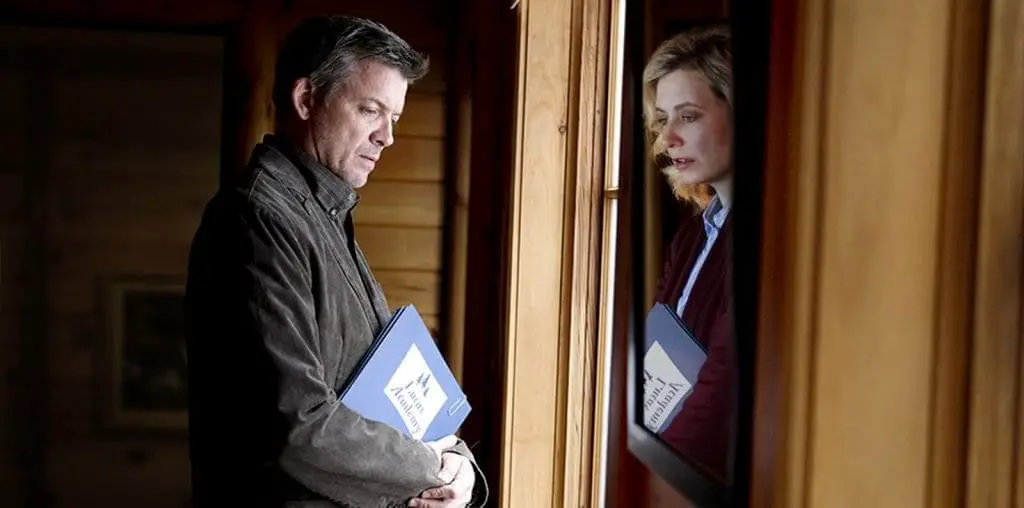

Being that this is a film where there are at least eight characters gathered together in one house, there is immediately the thought of the risk of everyone pouring out their feelings and us trapped in that same house. Perhaps because of his experience, or because he just figured out that heart-to-hearts in this intimate house don’t work as well as each of the characters encountering each other at one time or another, Stockman introduces Keith, introduces Emily, and introduces Anita’s other sons, Barry (Tom Cavanaugh) and Matthew (Glenn Howerton, who, it’s learned in the audio commentary on the DVD, made this film before starting on “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia”) gradually. The morning after Keith has come in, Barry arrives, jabbering on his cell phone, very much a busy businessman who managed to fit this visit into his schedule. He’s not used to what Emily is already used to and what Keith has already gotten used to. He’s disgusted by the bedpan Anita has puked in and has to throw out his tie because it landed in the bedpan. He tries to change the sheets, but uses ones that are too short, and then uses another set. But he’s there, and that’s important.

In some of the characters, Stockman goes too big in trying to create humor to offset the somber and saddening tone. Matthew, the aloof member of the family, arrives with his wife Katrina (Clea DuVall), the Bitch No One Likes. Barry asks her to take Anita’s latest dirtied set of sheets to the laundry, and she says that she can’t, because she can’t start her day without her coffee. It’s too obvious that she doesn’t care what happens in this family, and even in a deleted scene on the DVD, she’s trying on Anita’s jewelry, seeing what fits her for when the worst finally happens and she can take the jewelry. Then there’s also a scene where Barry, evidently disappointed by news he hears on his Bluetooth of a meeting being cancelled, decides to stay behind at home for a while longer, while his wife and kids fly back home. He wants his luggage, but the counter clerk won’t give it to him because it’s already been checked in. He tells her that it’s right there, right near her. She still won’t give it back to him, so he gets back there, takes it and heads for the airport exit, only to be prevented by two unusually well-armed guards. This doesn’t fit anywhere in the pattern of “Two Weeks.”

Those two Sally Fields provide another line of thought that lasts after the film is over. By being interviewed by Keith, it’s clear she wants her children’s memories of her to not only be that of what they see in her last days, of the hospice worker (Michael Hyatt, whom I recognized only from episodes in season five of “The West Wing,” so this is a welcome appearance) explaining how the morphine drip works, of Anita chewing on a sparerib at the dinner table with her children and her second husband Jim (James Murtaugh) and spitting it out, because her digestion system can no longer handle it. But in that scene, they follow suit, to keep up her spirits. She’ll still be there on that tape, for posterity, and she’ll still be there within her children because of the life she gave to them, physically and just by being there for them.

And maybe Stockman did the right thing by keeping Jim on the outer circle, sitting alone, perplexed by how Anita’s children have descended on her house, ignoring his feelings too. He’s married to her, after all. But I still feel conflicted, because shouldn’t he have had some moments to express how he feels about Anita’s impending death? Or would it have been too maudlin? Me, I would have liked to see more of him because even though he is a plain-looking actor, Jim feels too plain by not being there, even though he joins them at the bank to close Anita’s account and sitting at the dinner table with Anita and the children, chewing and spitting. Maybe it’s Stockman just trying to foster discussion after the film is over but it feels like he, along with Matthew, deserved just a little bit more.

There is one moment that defines the dignity of the film, what Stockman has been aiming for the entire time. He’s not just out to tell how he got through his mother’s death, but also in how it ties us all in. It’s after Anita’s death (no spoiler there), and her body has been taken by a man and put into a plain white van to be transported to where the body can be cremated. The van drives away and Keith and Barry just stand outside. Keith spots something offscreen and we see a car drive past, throwing a newspaper at the house next door. “It’s normal out, isn’t it?,” Keith asks Barry. It’s such a poignant moment, heartbreaking almost in how life just moves on. Nothing stops just because of Death. We, or our descendants, keep living. It’s a powerful message, one that we might not think of often, but there it is, magnified to follow us after the story is over. We just keep living.