“The Turandot Project” is really two very different movies in one: (1) an admirable behind-the-scenes look at the creation of a celebrated operatic production, and (2) a shameless propaganda vehicle for the government of Communist China.

The first film is interesting on several levels, especially if you love opera. In 1997, conductor Zubin Mehta recruited Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou (“Raise the Red Lantern,” “Ju Dou”) to direct the Florence Opera’s spectacular production of Puccini’s Chinese love story “Turandot.” Zhang never directed an opera before, and whether he actually directed the Florence production is left murky in this film (it looks as if Mehta had more than a few opinions in how the opera should flow). Nonetheless, the Florence production was a major success and Mehta decided to take this production to China for its very first staging in that country. This was a fairly curious decision, since Western opera is not especially popular among Chinese audiences.

Mehta pushed the reluctant Chinese government to keep Zhang as the director of the opera. Since the government banned many of Zhang’s films from being shown within China, Mehta’s persistence (which included presenting a gift of Indian mangoes to the Chinese Minister of Culture) was a triumph of his spirit. Almost immediately, the Chinese government bent over backwards in providing assistance for this special production. Beijing’s Forbidden City was converted into an amphitheater for the staging, while 2,000 people in rural China were engaged to sew the 900 new costumes needed for the show. Furthermore, 300 members of the Red Army were trained to serve as on-stage warriors.

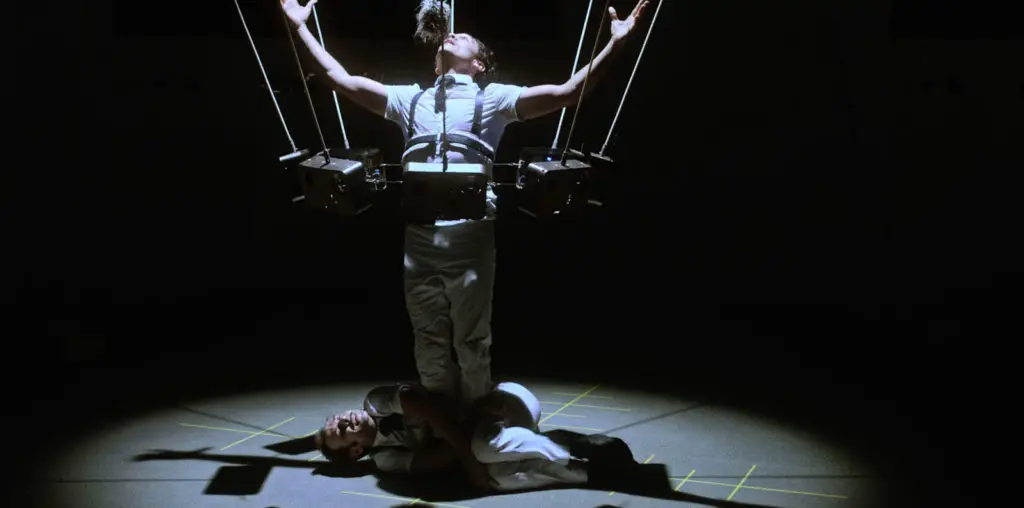

By taking cameras behind the scenes in the world of opera production, filmmaker Allan Miller (who won Oscars for his music-inspired documentaries “Bolero” and “From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China”) provides a rare peek into the complicated issues and personalities who collaborated and clashed in this particular “Turandot.” Unexpected surprises pop up delightfully: soprano Sharon Sweet does a mild diva snit in rejecting a headdress as “ugly as sin” while lighting director Guido Levi does a full diva blast in openly criticizing Zhang’s talent and vision while snickering for rain so he won’t have time to set up the lighting to Zhang’s specifications (and, amazingly, the rain gods were on Levi’s side). From a logistics standpoint, it is amazing that this show ever got staged: a mix of Italian, German, English, French and Chinese languages criss-crossing endlessly and the fire regulations protecting the Forbidden City’s wooden structure made the use of local electricity impossible–no mean feat when considering the need for lights and speakers to surround the stage.

Had “The Turandot Project” strictly been a backstage pass to the making of the Beijing “Turandot,” it would have been a mildly fascinating work. Sadly, there is a second and far more subversive film at work here which serves the Communist Chinese government in its seemingly endless attempts to gain Western respect. In bringing “Turandot” and its international trappings to Beijing, the Chinese government enjoyed a spectacular publicity coup which was obvious throughout the pre-production and rehearsals. Zhang himself states the production is a way for China to show off for the world and he is frequently shown berating the stage crew not to muck up the show, fearing the opera would look like “an international joke” and would reflect poorly on China. Opening night itself seemed to have more Westerners in the audience than Chinese, which is completely unprecedented for any Beijing musical or theatrical production.

Of course, civilized nations do not need to “show off” for the world in such a heavy-handed and self-conscious manner , and it is egregious to consider how Mehta and his operatic band were played by a government which has no history of allowing freedom of expression (either artistic, political, theological or digital) for its own citizens. If anyone in the production had an opinion on the violent suppression of human rights in China, it is not captured on film.

Often, “The Turandot Project” trips itself up with evasive language and problematic images. The film briefly mentions that 2,000 people “from rural China” were hired to sew costumes… who are these people? Are there just 2,000 talented tailors sitting around the Chinese countryside looking to make theatrical costumes, or did they come from the ranks of the slave laborers within the Chinese penal system whose work has been well documented by human rights groups? Having 300 Chinese soldiers in the production is equally unsettling–where were these troops and their commanders a decade earlier when Chinese citizens seeking the basic tenets of a free society were massacred in Tiananmen Square, not far from the make-believe fantasy world at the Forbidden City? And what role have these soldiers played in the on-going persecution of members of the Falun Gong movement? “The Turandot Project” even has the tired old Communist travelogue tricks in an irrelevant brief interlude which shows towering skyscrapers, fancy apartment complexes and merchandise-thick department stores…what the hell does this have to do with “Turandot”?

In fairness, it is not likely that Miller intended his film to be a propaganda vehicle. But unfortunately, that’s how the film plays and these unsettling elements disfigure his production to the point that it is impossible to enjoy it. Too bad the Beijing “Turandot” itself was not captured on film in its entirety–it would have been a far more successful and much less upsetting work than this feature.