Since his 1978 breakthrough, “Gates of Heaven,” master documentarian Errol Morris has made a career out of exploring the psyches of oddballs, enigmatic loners, criminals and the occasional hero and/or genius. Morris’s latest subject is a little of all those things.

The subject of “The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara” is usually cast as one of the villains of twentieth century history. Described as fully assured of his own brilliance and near infallibility, the former Secretary of Defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson is considered one of the chief architects of U.S. involvement in the Vietnamese civil war, which makes him largely responsible for the needless deaths of many hundreds of thousands, perhaps over a million, civilians and soldiers. Even when he admits that war was a dreadful mistake years later, he does so in a way that avoids direct apologies and manages to make his enemies across the political spectrum hate him even more.

On the other hand, Robert S. McNamara — now eighty-six, but looking and acting years younger — seems genuinely concerned with the welfare of his fellow humans. “Strange” is literally McNamara’s middle name, but he’s not quite Dr. Strangelove. A calculating killer, McNamara has also saved countless lives. He seems to be sincerely motivated by humanitarian instincts as much as he is by Machiavellian imperatives. In fact, if he had only done a little less in his life, he might today be viewed as a desk-bound hero.

Nevertheless, the civilian body count started early in McNamara’s political career. Working under the ruthless military man Curtis LeMay during World War II, he helped plan the firebombing of Tokyo. Incinerating over 100,000 civilians, the attack was definitely a war crime. While many would argue that it was, in fact, a necessary atrocity, the death toll from the bombing was actually higher than that of the better remembered and more controversial dropping of the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Still, it was ultimately the decision of LeMay and his boss, Franklin Roosevelt. “Mac” wasn’t truly in power.

After the war, McNamara tells us he found a way to help save lives. As a Vice President at Ford Motor Company, he worked on redesigning cars, installing safety belts and creating steering wheels that didn’t impale drivers, saving untold numbers of human beings all over the world.

Later, as Secretary of Defense under JFK during the Cuban Missile Crisis, he may have been critical in fighting his old boss, the wildly hawkish General LeMay, who by all accounts was hell bent on nuclear apocalypse. Thus, McNamara may have helped save the lives of each and every one of us. To this day, he remains deeply worried about the prospect of an “accidental” nuclear war that could still eradicate us all, and he agitates for disarmament.

Not long after the Cuban crisis, of course, McNamara was busy engineering U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. If there is to be a final accounting on judgement day, God is going to need some pretty complex spreadsheets to figure where this one belongs.

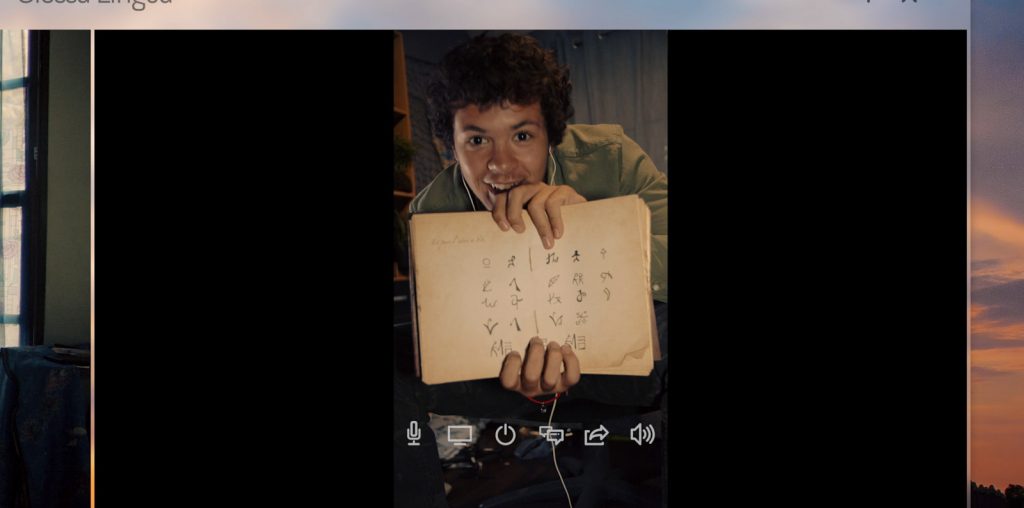

There is nothing simple about Robert McNamara and nothing simplistic about Errol Morris’s involving look at him. Deftly mixing historical footage with high definition video shot on Morris’s famous interviewing gizmo, the “Interotron,” “The Fog of War” presents us with a man who simply cannot be easily categorized, even when he looks us straight in the eye.

At times, Morris presses his subject (as in prior films, we can occasionally hear the filmmaker’s wry, humorously aggrieved off-mike voice, gently prodding his subject or making a factual point) but McNamara seems unable to publicly confront issues of his own responsibility.

Is it because he cannot live with the thoughts of the burned babies and dead or crippled soldiers, or simply that he refuses to deal with issues that will tarnish his image? In fact, one of the eleven “lessons” referred to in the film’s complete title is not to answer the question you are asked, but to answer the question you wish you were asked. Even if McNamara did answer such questions in a complete and fully reasoned manner, it’s not certain it would make any difference. Another of McNamara’s lessons is: “Rationality will not save us.”