BOOTLEG FILES 282: “The Prince of Peace” (1951 filmed record of an Oklahoma-based Passion Play).

LAST SEEN: We cannot confirm the last public screening.

AMERICAN HOME VIDEO: None.

REASON FOR BOOTLEG STATUS: The film was never commercially released on DVD – someone must have the rights.

CHANCES OF SEEING A COMMERCIAL DVD RELEASE: It is possible, most likely from a small Christian label.

Religion and cinema have always been something of an oil-and-water mix. Filmmakers usually fall into one of two traps when approaching this subject: a sense of vulgar spectacle that steamrolls the genuine emotional aspects of religion-based themes, or an icky cluelessness that trivializes the psychological depths of religious experiences, to the point that God is presented as something of a short-order cook who serves up miracles upon instant requests.

“The Prince of Peace” is something of an exception. It is not so much a film, but a filmed record of an amateur Passion Play staged in the Wichita Mountains at Lawton, Oklahoma. The enthusiasm of the play’s participants clearly runs ahead of their experience in theatrical presentation. Yet the work is so strange that it almost qualifies as the cinema equivalent of folk art: a primitive expression of raw, untrained talent that has yet to synchronize the process of bringing great ideas to life.

Viewing “The Prince of Peace” today is somewhat difficult, since half of the original film is not available for viewing. The production was a two-part presentation, with the first part being a silly melodrama about a six-year-old girl with a precocious sense of religious enthusiasm. The child was Ginger Prince, a cheerful moppet who was being prepped by producer Kroger Babb to be the next Shirley Temple. Sadly, young Miss Prince was a severely inadequate screen presence. Bosley Crowther, reviewing the film for the New York Times, complained that she “should be studiously kept away from a microphone until she learns how to sing.”

Needless to say, many people shared Crowther’s concerns. “The Prince of Peace,” which played theatrically throughout the 1950s, was recut after its initial run and the Ginger Prince portion was taken away. What remained was the 70-minute Passion Play portion of the film – this is the one that can be obtained via bootleg DVDs – and that has to be seen to be believed.

All of the actors who recreate the life of Christ are non-professionals, which is fairly obvious from the get-go. It also appears that none of them ever ventured far from Oklahoma, as everyone speaks in the flat-vowel, twangy Okie dialect. I am not making fun of that manner of speech, but it seems wildly out of place when the script is rich with the “thee, thy, thou” manner of Old English elocution. Plus, it is jarring to hear the faithful refer to Jesus as “mare-ster.” Film critic Kenneth Turan would famously complain that this was the only film that should have been dubbed from English into English.

Jesus is played by Millard Coody, a bank clerk who seems to have been chosen to play Christ because he is the tallest man in town. With a flowing wig that recalls Farrah Fawcett circa 1976 and a pasted-on beard that looks ready to fall off at the first sign of wind, Coody seems more profane than sacred. And when he talks about “Mah ‘ow-wah a’ sorrah,” you have to wonder if Mary and Joseph made a wrong turn at Tulsa while fleeing from Herod.

Actually, the Nativity takes place outdoors. Since the play is staged in an open-air amphitheater, all of the scenes are presented al fresco. Thus, the infant Jesus (a cute, uncredited baby) is lying in a manger outside of the stable. There are no formal sets, but there are a number of facades that appear to have been slapped together with stones and rocks that were gathered from a local park. Watching this play, one might assume Jesus never set foot in a house. Even the Last Supper is stages like a cheery patio picnic, complete with overflowing bowls of oranges and apples.

A careful viewer can also spot telephone poles in the far distance – perhaps Jesus was able to call home during His three years of ministry?

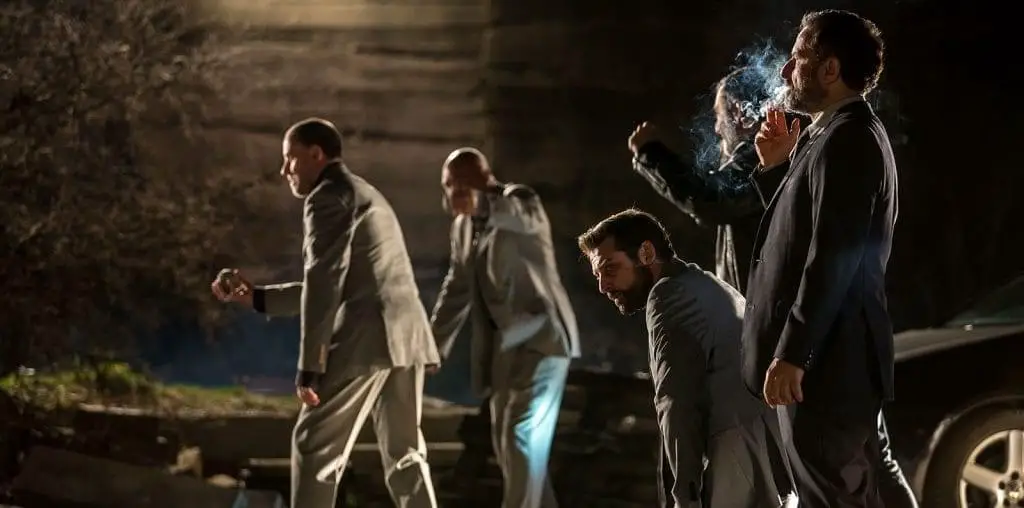

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of “The Prince of Peace” was its cinematography – while most no-budget indie flicks of the era were strictly black-and-white affairs, this flick was lensed in the cheapo Cinecolor process. This helped present the play’s astonishing costumes, which consist primarily of vibrant pastel hues. The costume designer clearly didn’t pay much attention to historical accuracy – the women look like they emerged from Renaissance paintings, the men are wearing nightgowns, and no two Roman centurions have the same uniform. But in Cinecolor, the emphasis on bold blues, summery yellows, and soothing pinks creates a Gospel that cannot be accused of being monochromatic. Judas Iscariot, not surprisingly, is clad all in black. (He also has a wig that is similar to Louise Brooks’ Lulu-era hairdo and a handlebar mustache that demands to be twirled.)

Incredibly, audiences back in the day found nothing wrong with any of this. Bosley Crowther’s New York Times review noted that the Broadway theater where “The Prince of Peace” played had no empty seats on opening day (so much for Manhattan sophisticates!). Kroger Babb, the legendary exploitation producer, initially released the film in his carnival-worthy huckster style in the early 1950s, while K. Gordon Murray re-released in later in the decade with his own brand of showmanship. It also played as “The Lawton Story” in Oklahoma, where it was especially popular.

It is too easy to make cruel jokes at the expense of “The Prince of Peace.” The intentions of the play’s creators and cast were clearly in the right place, and the camera unfortunately magnifies the production’s inadequacies without taking into consideration the genuine religious conviction that fueled the effort. In viewing this today, we can easily forgive their clumsiness – and be grateful that this was their one and only movie.

IMPORTANT NOTICE: The unauthorized duplication and distribution of copyright-protected material, either for crass commercial purposes or profit-free s***s and giggles, is not something that the entertainment industry appreciates. On occasion, law enforcement personnel boost their arrest quotas by collaring cheery cinephiles engaged in such activities. So if you are going to copy and distribute bootleg videos and DVDs, a word to the wise: don’t get caught. Oddly, the purchase and ownership of bootleg videos is perfectly legal. Go figure!