You wouldn’t expect Cannon Films, financiers of dreary Charles Bronson and Chuck Norris revenge flicks, to be responsible for one of the great black performances of recent history. Indeed, Morgan Freeman’s memorable, Oscar-nominated portrayal of Fast Black was one of the great performances, period, of that era, and introduced to us to one of the great acting talents of our generation.

When Cannon agreed to finance “Street Smart” in early 1987, it was only on the condition that the film’s star Christopher Reeve appear in “Superman IV: The Quest for Peace” after Cannon acquired the superhero property from Warner Brothers. This was important to Reeve, who had David Freeman’s “Street Smart” on his shelf for years, before being attracted to it. Budgeted at three million dollars, “Street Smart” was shot in Montreal to save money, as the film was just one of the thirty projects the company had in development at the time.

Joining Freeman and Reeve in the cast was Kathy Baker as one of Fast Black’s hookers, Mimi Rogers as Reeve’s girlfriend, as well as Andre Gregory, the star of “My Dinner With Andre.” “Street Smart” was directed by Jerry Schatzberg, who had also directed “The Panic in Needle Park” and “Scarecrow,” both of which starred Al Pacino.

“Street Smart” stars Reeve as a New York magazine reporter who makes up a fictional story about a colorful and dangerous pimp. After the story gets published and causes a media sensation, the district attorney becomes convinced that the pimp in the story is really Freeman’s character, who’s on trial for murder. The district attorney subpoena’s Reeve’s notes, but as we know, there aren’t any notes.

It’s then that we’re introduced to Freeman’s character, the powerful, ruthless, and charming pimp known as Fast Black. As Reeve desperately tries to cover his tracks and go back and do the story he should’ve done in the first place, Freeman senses a golden opportunity. He quickly figures out Reeve’s dilemma and offers Reeve a Faustian bargain. He’ll supply the fictional story if Reeve will give him an alibi. When Reeve refuses, Freeman shows Reeve and us, the audience, how dangerous he really is.

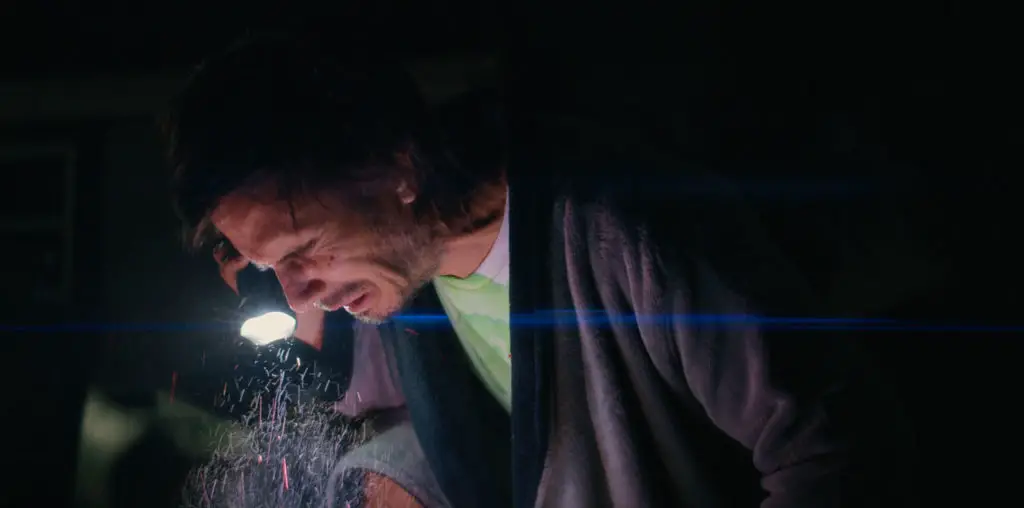

Freeman does this in a scene where he, Reeve, and one of Fast Black’s hookers are in the front seat of a car. Freeman holds a knife up to her eye and threatens to cut it out. Reeve objects and Freeman threatens to kill him. Then he lets the hooker go and we realize who the message was meant for.

Like the best villains in the movies, Freeman is at his most dangerous, or most evil, if you will, when he’s charming. And he can be charming. He even charms Reeve’s girlfriend and Reeve himself, who gradually introduces him to his world of snobby New York magazine types.

But like Edward Fox in “The Day of the Jackal,” he is a ruthless hunter who will destroy and kill anything if he feels the slightest threat to himself. Freeman is facing jail time, and this is something that is not acceptable to him, in any form, at any price. It’s at this point we realize that Freeman’s charming self is a cover for a deep anger and sickness. For Fast Black, it’s not a matter of ethics, but of survival. That’s the street.

And yet, “Street Smart” is not a perfect film. The Reeve character is stiff and uninteresting. Reeve’s ascent from a magazine reporter to a big time network reporter is unconvincing and unbelievable and his tired relationship with Rogers serves no real purpose in the film.

Actually, to be more precise, “Street Smart” is two movies in one. The first story is a largely-hollow satirical view of the New York magazine industry and Reeve as a publicity hungry, overnight TV star.

But it’s the second story that holds us, when Freeman and Kathy Baker, in an excellent performance, engage in a diabolical cat-and-mouse game. Baker’s character has become friends with Reeve, and when Freeman learns of Baker’s plot to help Reeve destroy him, he sets out to kill her in a chilling scene near the end. He appears like a monster to Baker, who’s waiting for Reeve’s character to rescue her. Baker, we learn, is a small-town girl, dragged onto the streets, but who still has real feelings.

Most importantly, “Street Smart” is an example of how a film, however flawed and uneven, can be enlivened by a true revelation, namely Freeman’s performance as Fast Black. Often we see movies that are far from perfect, but in “Street Smart,” we see a film that has two perfect elements in the performances of Baker and, of course, Freeman.

Freeman’s performance, which made him a star, and Kathy Baker’s performance are examples of how an imperfect film can be salvaged by performances that simply take our breath away. “Street Smart” is not a great film, but it contains greatness.