In Iraq, where the fighting remains constant in pockets of the country, filmmaker Michael Tucker went “over there”, as NYPD Blue’s Steven Bochco now puts it, to take a look at the current situation in all its forms. Originally making a film about an armored car salesman, his focus switched to 400 American troops who lived in one of Saddam Hussein’s palaces, which was given to his son, Uday. Gunner Palace was a result of that, the first film to really get into Iraq where the networks don’t go. Wolf Blitzer doesn’t wander these spaces.

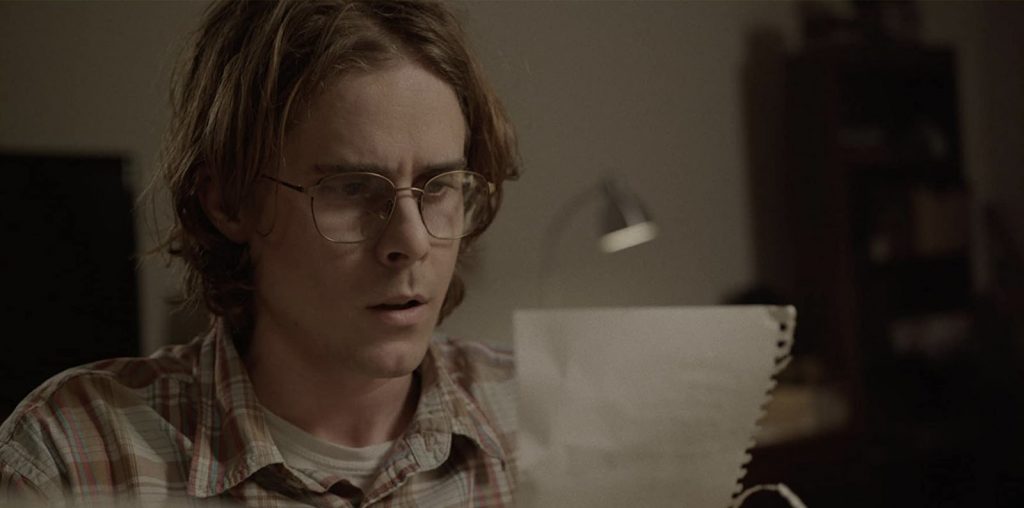

Michael Tucker spent some time with Film Threat, discussing his experiences in Iraq as well as the process of “Gunner Palace”.

How long were you watching the war on TV before you decided to head over there and tell the stories that weren’t told? ^ The first time I had the opportunity to go was May 2003, so when we arrived in Baghdad, there was still stuff burning, there was still looting going on, but there was no sense that the insurgency was going to start. It felt relatively under control. And then, I was actually there doing a film about an armored car salesman, not military vehicles, but ones for civilians. Just through that summer, we started meeting a lot of soldiers and we got a sense that what we were seeing wasn’t what we were watching on the news that night, and that seemed like a good enough premise for a film. What is the real story? What is this place really about?

How did you come upon the troops of Gunner Palace? ^ A friend of mine was a cameraman and he had actually been with the 2/3 Field Artillery a few weeks before, and he said that these guys were in a palace, they were in this really hot neighborhood, the sector was really active, that it was a great backdrop, that it was Uday’s palace and it had that swimming pool of all things. It was extremely hot at the time and it just seemed like a good place to make a home base. It was attractive. All in all, the unit, the location, the neighborhood, everything had good raw ingredients for something visual.

The only connection I had made between “Gunner Palace” and “Fahrenheit 9/11” is that both you and Michael Moore mentioned that some of these soldiers in the war are from places we’ve never heard of. We know of New York, New York, but not Argyle, New York. ^ They’re from everywhere. Wilf from the film, he’s from Colorado Springs and a completely suburban character. You and I can probably identity with him pretty well. He’s not that different than I was when I was his age. Wilf is basically irreverent, punk rock. He basically hates everybody.

Now in the film, we see the soldiers’ side, talking to the camera, musing over the impact of the war. What were your feelings as you captured these raids and talked to these people? ^ As far as the raids, like going through someone’s home, those are the most intense thing they’re doing. The raids are where there’s a confrontation between the American forces and the Iraqis as to what was really happening, they’re very volatile situations. The basic thing is that you go into a house that’s extremely violent and you have to be able to detach yourself from what’s going on around you and you can’t be sitting there making judgments as you’re filming; you just film. And you’d want to capture as much that’s going on in that house as possible. The more transparent you are, the more you get. You have to keep your opinions to yourself, which is hard because they are extremely emotional situations. You’re always going to have your own opinion as to what’s going on, but that’s not the business we’re in. The thing for me, separating what’s happening on the street and what’s going on when you’re trying to talk to these soldiers, the goal is to try to get them to open up in any way possible and to get them to talk freely about what they were experiencing and so, of all of our footage, 100 hours of it, was sitting late at night, smoking cigarettes, and getting people to talk, trying to get them to be honest, not as if they were in media training or trying to be provocative for the sake of being provocative. The part that I love about some of these guys, especially Wilf’s is that his goofiness really came through, his black humor. It was something that was just there that manifested itself, that the camera was really transparent to it. The guy’s a clown. He was a clown with or without the camera, it was just one thing that was happening.

There’s a moment where at about the 50-minute mark, you return home. What was that like for you to come back from Iraq to the general tranquility of your space? ^ A lot of people don’t understand that. I put that in because it was extremely deliberate. It was put in there for the soldiers because the minute they see that, they relate to it and they say, “Yeah, that’s exactly what it feels like. Going from complete total chaos to where something as normal as a cup of coffee, these are kinds of symbols, the fact that you can make your own cup, that it’s familiar.” You’re talking about war, where there’s no decompression. You’re at Baghdad International Airport and then five hours later, you’re in Germany. So it’s very intense. The thing that always shocked me was that you’d come back from a place like that and then try to communicate with people, when 12 hours ago, we were rolling with troops in Baghdad and all of a sudden, we’re home watching it on the news. It seemed that that was really important to communicate that disconnect. People really have no idea of what the experience is, and they think they know because they watched it on the news but they don’t know because they haven’t been there.

What’s your take on the state of news today on all these cable and satellite channels, and even locally? ^ I actually think the news underestimates the audience. They have not been given the chance to care about these people, or the subject. We want someone else to blame, rather than face the pictures and the facts. They want to make decisions about what direction we should be going; we just like to point a finger at someone.

With the tours you made around the country with the film, showing it to all types of people, what was their reactions? Were some politically colored? Did some simply like being able to see more than they’re usually allowed by the news? ^ With audiences, it’s like, as long as people cared about the subject, it was constructive, rather than the yelling and the screaming [found on pundit programs].

There’s a moment in “Gunner Palace” that’s really shattering. On the soundtrack, you have these News Minutes running, voices giving the latest news and one story talks about soldiers not having to worry about student loans while they’re in Iraq. Suddenly, there’s this loud explosion and I automatically thought, “Yeah, right! They’re really going to worry about unpaid bills right now.” What did that piece of the film represent to you? ^ The story about student loans represented to me that disconnect. Until a couple weeks ago, I have never experienced fear so intense such as being in a convoy and when a car doesn’t respond to you via your hand signals, you shoot them. Everyone’s on edge, no matter how optimistic they sound, including those in Washington.

Even so, with that edge, the calm moments that you chose include some of the men visiting an orphanage and a chaplain holds a baby in his arms, wondering where the mother is. Even with all that’s going on, with thoughts of worry conjured up by the baby being without a mother, there’s definitely hope there. They’re trying. ^ There are positive things in the film. You sensed optimism here and there. Then again, when there are gun battles raging in Baghdad, and people are afraid of being kidnapped and their kids being kidnapped and crime is total out of control and you’re living in a militarized culture and they’re talking about how rosy and great everything is. It never changes the fact. A couple of weeks ago, I was in a neighborhood and everything was peaceful and it felt like things could get better and we were talking to the people on the street and 3 weeks later, three car bombs went off there. There’s always that separation between what war planners are saying and what war fighters are doing.

Since the film was made, how often do you keep in touch with the troops there? ^ Most of them and all of them have re-deployed, so they’re all home. They ended up spending an average of 420 days in Iraq, but they thought their tour was going to be 3 months. As far as the main guys in the movie like Wilf, every couple of weeks I talk to him or e-mail him. The film has very much grown outside of being a film and there’s all these stories intertwined, and I think it would have made a better book than a movie.

What is Fisher House and how is “Gunner Palace” involved? ^ Fisher house is a group based in DC that provides assistance to the families of wounded soldiers. We are donating a portion of our DVD revenue to them–I hope, if we get the numbers we want, that we’ll raise at least $50,000 for them.