What do you do when you’ve decided to make a movie based on a book entitled Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho but haven’t been able to secure the rights to use even a single frame of Psycho in your film? Well, if you’re director Sacha Gervasi and screenwriter John J. McLaughlin, you attempt to compensate-or perhaps to distract-by making a movie based mostly on inference, innuendo and speculation instead.

Hitchcock is being marketed as a portrait of a master moviemaker in the process of creating the picture which would prove his greatest commercial success but it’s less about going behind the scenes than going behind closed doors. Anthony Hopkins gives one of the least convincing performances of his career in the title role. It doesn’t help that he gives it in a fat suit and under equally unconvincing facial prosthetics or that much of the time he sounds more like Hannibal Lecter than the film’s subject. Helen Mirren costars as Alma Reville, the maestro’s wife and collaborator.

In adapting Stephen Rebello’s 1990 chronicle of Psycho’s production, the screenwriter has taken a number of liberties. The number is a large one. While Hitchcock begins with the director coming off the triumph of North by Northwest and resolving to show audiences he still has a few tricks up his sleeves at 60, the movie’s focus quickly shifts from public relations to private ones.

The filmmakers proceed to offer a portrayal of the couple’s domestic life for the most part unencumbered by fact, an existence McLaughlin imagines as a cross between an Eisenhower era sitcom and a soap opera. Many scenes, for example, concern comical attempts by the corpulent Alfred to indulge cravings for food and drink without getting caught in the act by Alma. “There are calories in that, you know,” she nags upon discovering an empty wine glass he’s stashed while reading the just published Psycho. The pair talks shop at night tucked into twin beds like Wally and Theodore Cleaver.

I’m not sure which is more tiresome-the series of fantasy sequences in which Hitchcock interacts with Ed Gein (Michael Wincott), the Wisconsin serial killer who provided the basis for the main character in Robert Bloch’s bestseller, or the love triangle Hitchcock‘s creators fabricate. You’ve got to wonder about the motives of a writer and director who no sooner informs the viewer that Alma made invaluable contributions to her husband’s work then paint her as an attention starved woman capable of betraying him with a studio hack (Danny Huston).

I found myself wondering about the filmmakers’ motives a lot. I’m not sure why they went to the trouble of dramatizing Hitch’s struggle to get the milestone horror movie made over the protestations of Paramount brass (even taking out a loan on his home so he could finance it himself) when their real interests clearly were his idiosyncrasies and flaws.

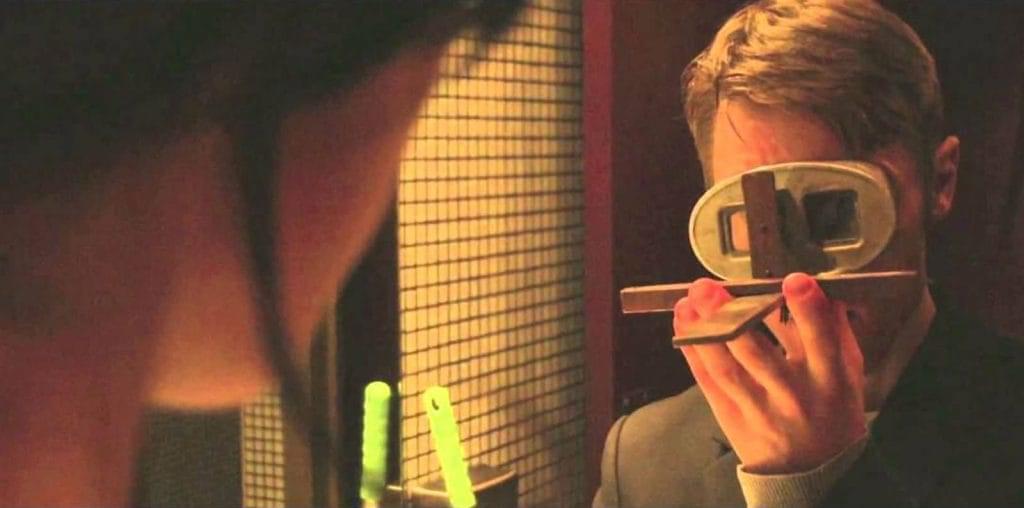

An inordinate portion of this film’s running time is devoted to unflattering depictions of well-known foibles and weaknesses. We watch Hopkins sneak snacks like a naughty boy, gulp secret drinks, peer through his office blinds at actresses on the lot and salivate over 8 X 10s of leading ladies like he’s looking at internet porn. And, as if that weren’t demeaning enough, we watch him spy on Vera Miles (Jessica Biel) through a hole in the wall as she undresses even though there’s zero evidence to suggest Hitchcock ever did such a thing.

So much for the mystery as to why permission to use that footage was denied by his estate. What can one say except that Hitchcock is a mediocre film tangentially concerned with the making of an immortal one. Anyone with a passing knowledge of either is unlikely to learn much of anything new about the movie or the man because Gervasi’s latest stretches the truth so frequently and so far it ends up less the story of the genius behind Psycho than a bunch of biographical hooey that’s for the birds.