Few things in micro budget indie film are easier than being the gaffer when shooting a field far away from electricity. There’s really no way you can possibly be expected to get electricity that far, if for no other reason than the production probably hasn’t rented a generator. And without a generator, no electricity. No electricity means no lights. If you’re far enough out there, in a remote enough location, you can’t even block the light. Basically, you can bounce it around a bit, but 99% of the time, that’s it. You’re limited to what you can carry and the whims of the “Great Gaffer in the Sky”.

So you spend a lot of time shading your eyes, looking up at the cloud pattern, and trying to figure out what exactly the clouds are going to do. You want to know ahead of time if there’s some dark clouds on the horizon that’ll make everything a lot darker or, even worse, if the sun is about to come out, thereby negating that fantastic soft box you’ve given the DP.

The Great Gaffer in the Sky has some fantastic lights, but little concern for how they affect your film.

But other than looking thoughtfully at the sky, there’s not a whole lot you can do. You stay near the DP, just in case he needs something, but mostly you just stay out of the way and every so often offer some encouragement when needed.

Even that isn’t so easy. There’s a common plant in the UK called the nettle. It’s apparently all over the place. Hell, it’s even listed on the call sheet. I’ve never heard of it, even though Wikipedia seems to think it’s all over North America. I grew up in the woods of Maine, and I’ve never heard of it. People will tell you to look out for them, and for good reason. They f*****g hurt. And I don’t mean like bee sting hurts. I mean 6 hours later you can still feel it.

I’m told you can boil them into a tea, but I’m not sure why you’d want to. Although, this is the UK.

The scenes in the field are pretty simple, transitional dialogue scenes. A minimum number of set ups and then we’re done. So we trek out to the field to find a good spot, with the expectation that the cast is right behind us.

They aren’t.

But we have a few things we can do. We’re still waiting for one of the camera guys, but then he shows up and still no sign of the cast. Ten minutes go by. Twenty minutes. People are sitting down in the grass. Eventually they make their way out to the location, but they’re unrehearsed. Add to that the fact that it turns into a moving shot, with a handheld camera going backward on some uneven ground and you’ve got a scene that takes a lot longer than scheduled.

There’s a truism in construction that once the crew stops working, it’s difficult to get them started again. At least, that’s what they say whenever I watch FLIP THIS HOUSE. Same thing applies on a film set. Once they’ve taken a break, it’s hard to get them going again. It’s just human nature. So time spent on rehearsal after the shot is ready is usually time wasted, plus the time wasted trying to get things back up to speed.

We finish in the field, then it’s back to the farm, where a new problem has emerged.

In the story, the judge (Bill Fellows) is a pretty well-off guy and therefore drives a pretty expensive car. The production, doing their due diligence, found an Audi to serve as a picture car. Only to find out just before production started that Bill cannot drive a stick shift. (I’m told the stick shift is much more prevalent in the UK than in the US.) So they can’t shoot footage of him driving, which will be tricky because there’s several pages of the script that revolve around that.

What to do?

Producer Zahra Zomorrodian has something that sort of looks like green screen material in her car and DP Richy Reay is pretty sure he can key it all properly, so it’s up to the G&E team of myself and Grip Ben Moseley to make that happen. And we have to do it outside.

Loyal readers of A Year Without Rent will recall how on Sean Gillane’s CXL, we had to figure out how to rig a green screen on the windy sidewalks of San Francisco. It’s the sort of thing that rarely comes up, but thank goodness it did because now I’m able to use the tricks we figured out on Sean’s shoot and put them to use here, only on a much bigger scale. Oh, and we have about a quarter of the gear we need to do it.

But someone says to ask Jerry if he’s got anything in his van. Jerry is the sound guy who shows up in a panel van full of gear. Sure enough, he’s got a couple of light stands with a T-bar attachment that we can affix the top part of the green screen to. The bottom needs to be stretched down to the ground and held in place, but we don’t really have anything to hold it tight uniformly all the way around the car. So we start looking around the farm for heavy stuff. We find some metal bars to help weigh it down and some very heavy grey things that are about 4 feet long and used in a parking lot to stop a car from going any farther. I have no idea what they’re called. We have 3 of those and since we’re really low on sandbags, they go on the c-stands.

We still need more sand.

By this time, Ben and I have commandeered the two runners and the 1st AC James Grieves to help. I’m in one of those spots where I’m holding something that probably won’t stay up by itself when we run out of sand. I look at runner Jonathan Teggert and James and tell them I need more sand.

“We don’t have any.”

“Well, figure it out.”

Five minutes later, they come back with a small (roughly 1 foot wide and 2 feet long) burlap bag filled with rocks. And you know what? It works. It actually works really well. Use a cable tie to cinch off the top and you’ve got a bag that’s more versatile than a sandbag, and just as heavy. You can distribute the rocks as needed, perfect for wrapping the bag around the base of a light stand, and they’re easy to pack up at the end of the shoot.

The whole green screen is stuff like that. One of the more DIY things I’ve ever done.

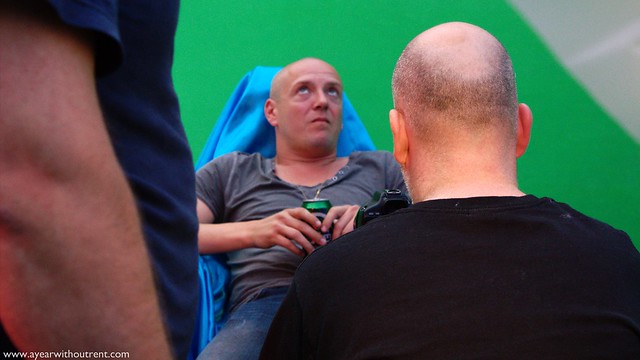

Then there’s a wait for the actors to get rehearsed. We shoot one half of the scene, then the car has to turn around to do the other half. And, yes, we simulate the car moving by pushing up and down on the hood.

The final piece of the day is a dream sequence where a scantily clad girl pours drinks down our actor’s throats. Smartly, it’s the last thing we shoot. Almost like a carrot on a stick to keep people moving.

And that’s it for day 2.

Filmmaker Lucas McNelly is spending a year on the road, volunteering on indie film projects around the country, documenting the process and the exploring the idea of a mobile creative professional. You can see more from A Year Without Rent at the webpage. His feature-length debut is now available to rent on VOD. Follow him on Twitter: @lmcnelly.