Still unable to remember the past, Kitty’s forced to rely on the kindness of people who may or may not be strangers. Because he insistently claims to be her husband, Kitty is compelled to believe Jake. Jake describes Kitty as a swimmer, a dancer, and a person who creates their own world and succumbs to it completely. In the beginning, Jack’s motive is unclear. The premise alone is jarring and disturbing, yet You Go to My Head is a subdued affair about two people falling for each other all over again, except their past doesn’t exist. Is it even possible to love somebody else when you don’t know yourself?

Bafort’s Kitty is svelte and confused, communicating her character’s dubiety and vexation through striking facial expressions. As amnesia continues to pique Kitty, Bafort’s performance is fittingly withdrawn, and in return, Bafort’s body language does most of the speaking. Cvetkovic’s Jake is abject and self-pitying. While what Jake ends up doing is reprehensible, a little part of me is empathetic. In fact, Dimitri de Clercq doesn’t necessarily paint the guy as a monster, but as a lonely man who did a monstrous thing to experience a deceptive love.

As Kitty and Jake gradually fall into each other’s embrace, there lies an ethic plight. Jake sacrificed all of his morals into duping a susceptible woman to believe she is his wife. Is it because love makes us all vulnerable? Can years of loneliness make us do the unthinkable? But what happens when Kitty falls for Jake, without knowing herself? Kitty and Jake’s story is convoluted and unexpected; there are no simple answers here, especially when it comes to the intricate ending.

“…the film operates like an unworldly dream…”

Stijn Grupping’s stellar cinematography beautifully captures the Moroccan Sahara Desert setting. It is a breathtaking, yet deadly location with vistas, ancient sites, and bodies of water. With a hypnotic use of color, light, and sound, the film operates like an unworldly dream. The camera moves with grace and intimacy, letting every touch, glance, and exchange between the characters feel palpable. The architecture radiates so much history and craft, thus making it easy to appreciate the attention to detail. A swoony piano ballad opens the film and closes the film, counterpoising the scattered cacophony of string instruments that eerily disrupt the film throughout.

The mystery of Kitty and the gambits of Jake appears very Hitchcockian. Bafort and Cvetkovic both give heartfelt performances. The utilization of contemporary landscapes and elusive plot threads laudably imitates the work of Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni. Artsy and alarming, You Go to My Head won’t be the film many unsuspecting viewers will expect it to be, and it’s all the better for it.

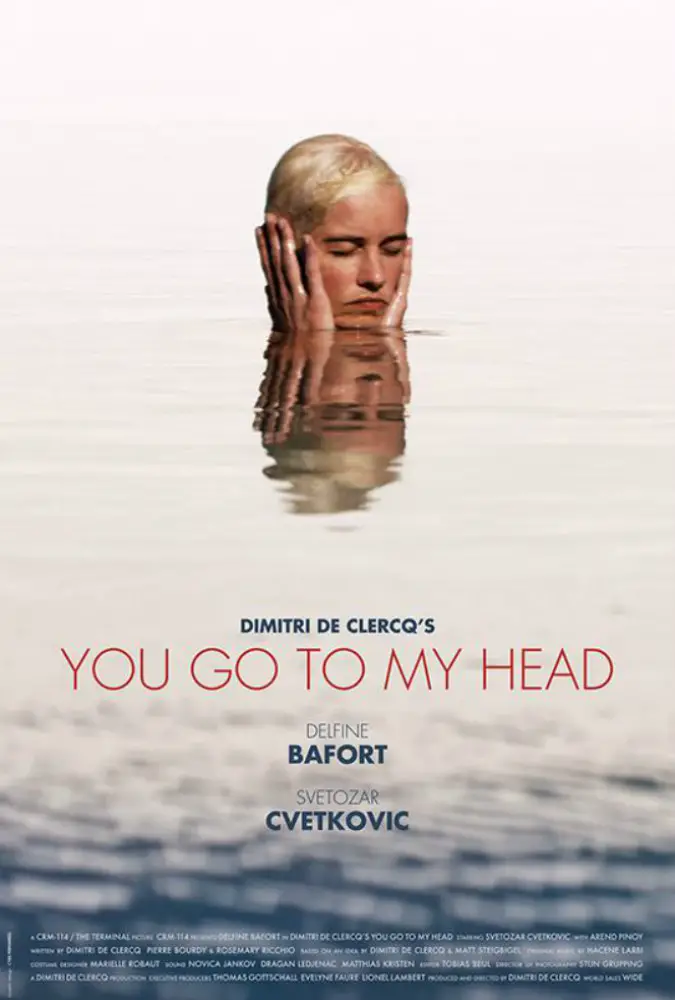

Mirrors have always shown us our faces and our bodies, making some of us feel self-conscious. Dimitri de Clercq’s use of reflections in the film are impactful in terms of reflecting unspoken feelings. Once you see yourself in the mirror, you start to see how unhappy or unsure you are. For Kitty, she’s unable to recognize herself because of the amnesia. There’s no definite way for Kitty to remember the past, and Jake exploits that to an extreme degree. And we’re left to probe this unorthodox romance, which effectively toys with our greatest fears: a fading memory, a hazy purpose, or dying alone. You Go to My Head is a warped and lush tale of obsession, deception, and romance that’ll certainly go to your head. It’ll just take some time.

"…doesn't necessarily paint the guy as a monster..."