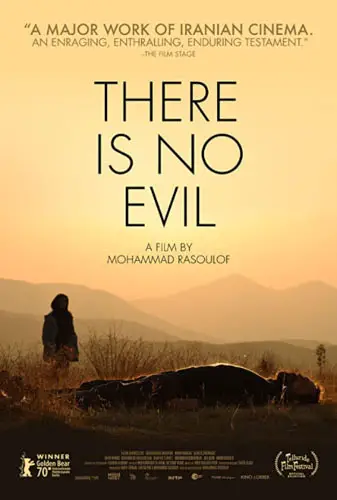

Iran has produced some of the most acclaimed directors in the world: Majid Majidi, Abbas Kiarostami, Asghar Farhadi, and Jafar Panahi, just to name a few. Writer-director Mohammad Rasoulof’s There Is No Evil deserves to be placed among the best Iranian films and reaffirms the filmmaker’s place in the pantheon of great Iranian directors. The dramatic anthology follows four different people, all of whom are dealing with the impact of the death penalty in their own way.

In the first story, Heshmat (Ehsan Mirhosseini) engages in the rituals of domesticity—he stares aimlessly at a television screen, picks up his wife from work and his daughter from school, picks up groceries for his mother, and dyes his wife’s hair. It is apparent that existential despair is gnawing away at Heshmat. On his drive to work, a red light turns green, but he does not press the gas. He stares at the green light; he is immobilized. Is he contemplating his life decisions? Is Heshmat pondering a way to change the course of his driftless existence? Or is Heshmat questioning his authenticity while staring at a green abyss signaling him to go? To reveal more would be serious reviewer malpractice on my part.

Pouya (Kaveh Ahangar), the protagonist of the second tale, is fulfilling his compulsory military service. When ordered to execute a prisoner, his conscience holds him back from going through with it. However, he knows that not following the orders puts his chances at a career and a passport — which is coveted by his girlfriend who wants to go to Austria — at risk. Will he find solace, or will his insubordination tarnish his reputation, and by extension, his life?

“…follows four different people, all of whom are dealing with the impact of the death penalty in their own way.”

The third segment involves young lovers Javad (Mohammad Valizadegan) and Nana (Mahtab Servati). Javad takes a few days off from military service to visit Nana. He arrives at a bad moment as Nana and her family are mourning the execution of her beloved teacher, who was imprisoned. The couple wonders whether their youth is blooming pointlessly in their home country. Javad’s past holds a secret that may tear apart his relationship with Nana.

The last story, which is perhaps the most powerful, involves a country doctor, Bahram (Mohammad Seddighimehr), and his wife, Zaman (Zhila Shahi ), awaiting their niece’s arrival from Germany. Once Darya (Baran Rasoulof) arrives, things get tense quickly, as secrets abound between the uncle and niece. This is a devastating capstone to a film that is emotionally resonant on every level. Plus, it connects to an earlier story, though saying more would ruin Rasoulof’s carefully crafted narrative.

Several of the characters in There Is No Evil are stuck in ethical dilemmas that pit their desire for upward mobility, whether in the form of a job, escaping the country, or establishing familial ties, against their moral distaste of executing another person. They are stuck in having to choose. The allusions to cars, traffic signals, airports, train whistles, and people running are no coincidence. These people desire to escape not solely from Iran but from facing these profoundly difficult ethical dilemmas. For Rasoulof, Iran becomes a kind of bottleneck which immobilizes people.

There Is No Evil could not evade Iran’s censors, so the film has not been shown in its home country. The themes of confinement and escape are indeed personal for Rasoulof. The challenge for Western audiences obviously does not involve censorship; it actually lies at the other end. Can North American audiences filter out Hollywood’s overhyped dross and find a way to appreciate There Is No Evil? Iranian cinema has always been very good at reminding you of your humanity, and Rasoulof’s anthology plumbs those depths perfectly.

"…very good at reminding you of your humanity..."