The eminent Fiennes siblings are known for their long-standing fascination with Russia. Joseph Fiennes played one of the Russian leads, Commisar Danilov, in Jean-Jacques Annaud’s Enemy at the Gates. His sister Martha directed Onegin, an adaptation of Alexander Pushkin’s classic, which starred the arguably most distinguished Fiennes sibling, Ralph. The latter – impressively! – learned fluent Russian for the lead role in Vera Glagoleva’s Two Women, which was based on Ivan Turgenev’s play; he also has the set-in-Russia anthology Petersburg Carousel on his slate, wherein he’s directing one of its short segments.

In his third feature directorial effort, The White Crow, Fiennes showcases his preoccupation with all things Slavic once again. The film focuses on the life and times of Russian ballet dancer Rudolph Nureyev, one of the greatest of his generation. It may be awkwardly paced and predictable to a fault, but Fiennes’ film does a masterful job conveying the essence and spirit of Russian ballet, the filmmaker imbuing the narrative with enough tasteful brush strokes and eloquence to make up for its patchiness.

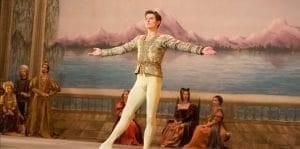

Somewhat ironically, the film begins with the definition of the term “White Crow,” which in Russia is used to describe someone who is “unusual, extraordinary, not like others, an outsider.” While the film would have surely benefited from such a description, its protagonist, Rudolf Nureyev (newcomer Oleg Ivenko, bearing an uncanny resemblance to the real dancer) can certainly be classified as the most ivory of birds. The White Crow traces the star’s trajectory, from his birth on a dingy Trans-Siberian train in 1938 to his arrival in Paris in 1961, and the consequent, against-all-odds conquering of the city’s ballet scene.

“…focuses on the life and times of Russian ballet dancer Rudolph Nureyev, one of the greatest of his generation…”

Despite starting late, the 16-year-old Nureyev is confident: “It won’t be long till everyone knows about me,” he says early on. Quickly learning English, the dancer sneers at his peers, mouths off to his chaperones and teachers, and resolutely pursues his goal of overcoming the stereotype of a “provincial Russian” by spiritedly immersing himself into the French art scene. “What you do isn’t technically perfect, sometimes even clumsy,” a friend tells Rudolph on a gorgeous Paris rooftop, “but your spirit is perfect. You take the stage.”

During his fervent quest, Nureyev gets in trouble for bedding girls (and boys) and partying all night; he lives with his prominent teacher Pushkin (Fiennes) and sleeps with Pushkin’s wife Xenia (Chulpan Khamatova); he dates a wealthy socialite Clara (Adèle Exarchopoulos). Eventually, after unprecedented success in Paris, he is forced to go back to Moscow, under the potential threat of execution. The final, intense sequence at the Paris airport displays directorial prowess sadly lacking in the preceding hodgepodge of character drama, art examination, biopic, and even elements of farce.

Ukrainian dancer and first-time actor Oleg Ivenko gives an uneven performance. On the one hand, his Nureyev is hypnotic on stage, suitably dedicated, while being temperamental and unafraid to be dislikeable. (“Stop showing me rubbish!” he tells a stupefied lady at a toy store.) Yet the earnest newbie has quite the load to carry: a character with daddy issues, masking ethnic and cultural insecurity with arrogance. His line delivery veers between wooden and overly expressive. If there’s an exception, it comes during the aforementioned finale, Nureyev’s unraveling portrayed by Ivenko with such poignancy, it’s truly a wonder it’s missing from the preceding 100 minutes.

“…Fiennes displays how art has the power to transcend politics and studies its transformative effect on people…”

Fiennes, the actor, excels again (can he do anything but?) as the gentle and sophisticated Pushkin. As a Russian myself, I sneer at most of Hollywood’s attempts to have characters speak my native language, yet Fiennes’ mastery of it is nearly flawless. On the flipside, his direction, while elegant, flounders intermittently, particularly when he cuts back and forth between timelines, slowing down the story’s momentum. He also lets David Hare, known for historical award-magnets The Hours and The Reader, get away with some cheesy lines. “I am poor company. I am on Valium,” Clara declares at one point. “I am better than Valium,” Rudolph responds cockily.

Fiennes displays how art has the power to transcend politics and studies its transformative effect on people: Rudolph finds dark inspiration in Théodore Géricault’s “The Raft of Medusa” painting. His desire to mingle with the intellectual/wealthy/capitalist elite is wisely observed but not criticized. “I know what he thinks of me,” Nureyev says about a waiter. “[That I’m] a peasant. F**k him! F**k Paris!” The dance sequences are expectedly lovely, as is Mike Eley’s cinematography, capturing all the glory of the Palais Garnier and Louvre in Paris, as well as the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg.

The White Crow demonstrates that, if perhaps not having yet mastered all of the nuances of directing an artful biopic, Fiennes possesses a keen eye for detail – and the man just can’t help but exude sophistication. He sees dance as a form of exorcism, a way to have people experience different, intangible worlds during tumultuous times. Here’s hoping one of our great living actors/directors – along with his prolific siblings – keeps finding inspiration in the incredibly rich annals of Russian history and literature.

The White Crow (2019) Directed by Ralph Fiennes. Written by David Hare. Starring Oleg Ivenko, Ralph Fiennes, Louis Hofmann, Adèle Exarchopoulos, Sergei Polunin, Chulpan Khamatova.

7 out of 10

Great review! keen and thoughtful