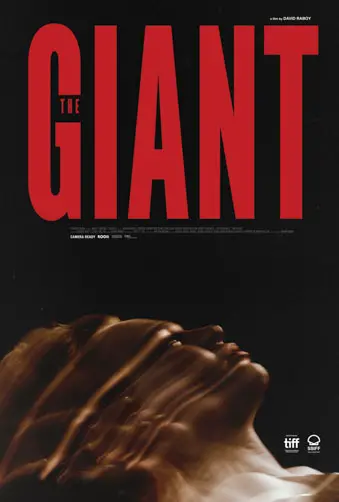

Writer/director David Raboy’s mesmerizing and maddening feature The Giant feels like the answer to a question that I’m not sure any genre movie aficionado has ever actually thought to ask: What if you took a slasher film, the kind that Roger Ebert derisively referred to as “Dead Teenager Movies,” and stripped out virtually everything a fan might reasonably expect out of it? The gratuitous sex and gore? Gone. Jump scares? Not present. The one-dimensional characters practically begging to be impaled with rusty garden tools? You get the idea.

In the absence of those things, what might take their place?

For Raboy, at least, it seems to be nothing but visual lyricism, elliptical coming-of-age dramatics, and – maybe most strongly – an oppressive, overwhelming sense of dread.

The premise, on paper, reads like bloody, low-budget drive-in fare. A murderer targets pretty blonde high school seniors in the summer after graduation. Nevertheless, the slow-moving film never once leans into its potential pulpiness, leaving any exploitation elements determinedly un-exploited. The murders all happen off-screen, the villain is never really glimpsed, and the terror is all existential, never visceral.

“…Charlotte and her circle of friends hear some mysterious screaming in the woods…”

Depending on one’s taste, the movie might play as a grim, melancholy tone poem, an avant-garde provocation, or, perhaps, a narratively inert slice of navel-gazing pretentiousness. What’s remarkable about The Giant, though, is that however they ultimately feel, viewers are unlikely to have ever seen anything else like it. For its admirers – myself included…maybe…I think – that might be enough in itself.

Love the film, hate it, or be completely mystified by it, one thing that The Giant absolutely has in its favor is its central performance. Assassination Nation star Odessa Young channels late-teenage ennui and barely repressed grief with a depth and restraint that’s rare for even the best teen-angst dramas. Her character, Charlotte, may be enigmatic, but her pain, fear, and uncertainty come through uncomfortably and resoundingly clear.

As the film opens, Charlotte is withdrawn, halfheartedly attempting to enjoy her last summer before adulthood sets in. What ought to be a sparkling, once-in-a-lifetime moment of freedom and self-actualization for her is clouded and choked out by the traumas that intermingle and metastasize in her head: her mother’s suicide, the year-earlier disappearance of her mercurial, unstable boyfriend Joe (Ben Schnetzer), and the impending loss of her high school friendships as everyone heads off to college. Charlotte’s best friend Olivia (Madelyn Cline) puts in a sincere, largely futile effort to cheer her up, while her police officer father (P.J. Marshall) keeps his distance, making only fleeting, almost ghost-like appearances in the dreary home they share.

"…plays by its own rules and moves to its own languorous rhythms."