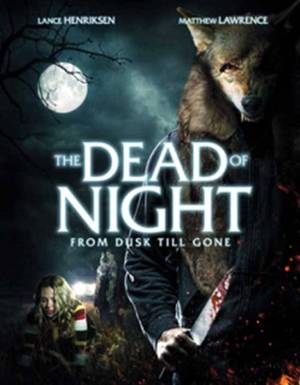

The Dead Of Night, written and directed by Robert Dean, wants to be a thriller, a drama about family bonds, and a slice-of-life about a small Texas town. It seems that the first-time filmmaker, though he has a handful of acting credits, has bitten off far more than he can chew. The script trots out one cliché after another, with minimal characterization. Though aspects and moments do work, any potential viewers who do not mind the tropes will tune out as the characters make one stupid decision after another.

June (Colby Crain) is about to move to Germany with her significant other, which her brother, Tommy (Jake Etheridge), is none-too-pleased about. Other townsfolk, including the diner owner where she works, Earl (Lance Henriksen), are sad to see her go but are much happier that she is living life her way. However, the ranching community is on edge after news of the murder of two people spreads.

“…the ranching community is on edge after news of the murder of two people spreads.”

Deputy Luke Walker (Matthew Lawrence) seems fixated on proving that it was Tommy, as the vehicle with the victims inside was found just north of his property. So, now Tommy has to find a way to clear his name, attempt to repair his relationship with his sister, and hope neither he, nor June, become victims of the nameless killers.

The frustrations of The Dead of Night rear their head immediately after the admittedly excellent cold open where the murderers claim their first (on-screen) victim. Starting at a rodeo, the announcer lists some sponsors then introduces one of them, Richard Hall (Mark Speno). The crowd grumbles at this, as Richard is not a real ranch hand, and his announcement of running for mayor is met with muted applause. Why is he so hated? Does he treat the animals and his employees poorly? Well, Dean never expands on this distaste (Richard is never a suspect in the murders, nor is he seen being questioned), so it comes across as pointless. It seems that this is only written in the screenplay because all small farming-type communities must have one “corporate” guy that everyone else hates. It does not work.

Given that character’s small role — he could be written out entirely and change nothing about the story — if he were the only example of such, it’d be nothing more than an easily overlooked oddity. But no, this lack of character development extends to every role here, minus Henriksen’s Earl, who speaks volumes with very little dialogue. June’s partner is never seen, only heard in one phone call, so the power of this relationship, the pull that makes her willing to move halfway around the world for love, is elusive at best, confusing at worst. Her friends, who are throwing June a surprise going-away party, fare even worse, as they have so few traits that audiences will not even remember their names.

"…the killers...communicate only in growls and grunts as if feral, and their motivations and backstory are never brought up."