With the Oscars just around the corner, the Film Threat writers review films during a time when the Best Picture was actually the Best Picture.

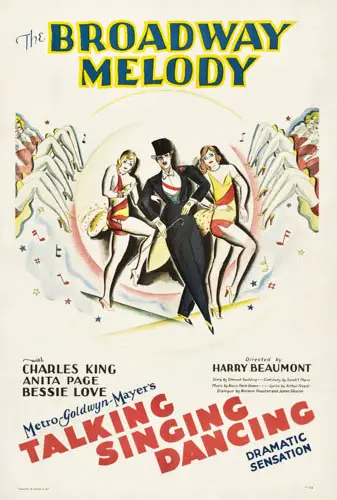

Upon its release on June 12, 1929, The Broadway Melody was a smashing success, making quite a tidy profit for MGM. At the time, critics hailed it as innovative, engaging, and holding appeal for just about everyone. Now, I’m sure you are thinking, “How is an innocuous romantic musical innovative?” The film, directed by Harry Beaumont, is considered the first-ever musical, creating a template that is still followed nearly a century later. In fact, it was considered so advanced and impressive that it won the Best Picture Oscar at the second-ever Academy Awards. So, how does it hold up to modern scrutiny?

Eddie Kearns (Charles King) has just written a new song, “The Broadway Melody,” which producer Francis Zanfield (Eddie Kane) immediately buys for his latest revue show. Eddie has a catch though — his fiancée, Harriet “Hank” Mahoney (Bessie Love), and her sister, Queenie (Anita Page), be included in the act. Unfortunately, during rehearsals, Zanfield doesn’t think the number is working, and to tighten it up, he cuts the women’s bit. While this infuriates Hank, Queenie winds up with a new, important role elsewhere in the show.

“Can Eddie and Queenie declare their love for each other…”

All the while, Eddie and Queenie grow ever closer, as the two haven’t seen each other in quite some time. But, not wishing to hurt her sister, Queenie starts up with known cad Jock (Kenneth Thompson). Fearing for her well-being, Eddie, Hank, and the siblings’ uncle Jed (Jed Prouty) attempt to wrangle her from the lothario. But, this results in distancing Queenie, whose star is on the rise, from her family. Will Hank and Queenie be able to repair their relationship? Can Eddie and Queenie declare their love for each other, or will it remain silent forever?

Look, The Broad Melody is a musical romantic comedy, so the ending is forgone conclusion. But it is important to keep in mind that this motion picture literally invented the beats most commonly associated with the genre. Beaumont’s direction is stagey, as was the style at the time (excluding anything directed by Sergei Eisenstein), with the camera rarely going beyond a medium shot, usually though a bit further than that. However, this does mean that the choreography and singing get to be seen in all their glory.

And what glory it is! For starters, the art and production design, headed by Cedric Gibbons, is great. The show being mounted looks truly ornate and exciting, something that would absolutely entice theatergoers then and now. The costumes are equally as extravagant and beautiful.

"…has secured its legacy and place in film history."