They finally arrive at Aila’s building and, although it is just minutes away from their encounter or Rosie’s house, this part of the east-side looks like a different world. The neighbors are nice, the place is well lit and maintained. When they enter the apartment, the differences between the two is even more jarring. We realize Aila can afford to live by herself in a very middle-class hipsterish apartment. Aila tries to break the ice and make Rosie comfortable, or at least, feel safe, but the teenager is one of few words and hard to read. Being an indigenous child who grew up in foster care, Rosie is now almost homeless or, in a way, forced to stay with her boyfriend. Rosie is also reluctant to answer Aila’s questions, who shares a lot and informs her about her mixed indigenous heritage, Kainai First Nation and Sámi from Norway (just like Tailfeather). But Aila understands that she is a privilege as a light-skin, educated woman from a good family. However, we learn that Rosie has nowhere else to go, and she does not want to go to her grandparents living in a remote town in another state. She does not want to be ‘one of them,’ a First Nation young woman going back to her ancestral home as a single mother of a newborn. She knows too well the power of judgment and, maybe, refuses to be seen as a failure.

“…an important story about two women, strangers who have so much in common and yet are worlds apart.”

There is no denying that Rosie is a realistic portrayal of a youngster with a difficult life. However, even though we feel sorry for her, she transpires as an “annoying teen,” not talking, almost hiding behind her wet blue hair, acting like a lunatic, or being rude (or worse) to those willing to help her. It makes sense that she expresses a real distrust in organizations and government as she had to deal with them many times before. She does not want to call the police to report her assault. This is because she does not like the way they – and many others – appear to be “tired of looking at us.” At some point, the duo visits a safe house run by another pair of lovely women. Rosie and Aila are welcomed by smiling and kind faces, hot food, and drinks. The warm fuzziness of it all felt like a much-needed hug amidst the desolation of the situation as we later grasp that it can take 6 or 7 visits before a victim decides to leave their abuser and “feel safer” in a safehouse.

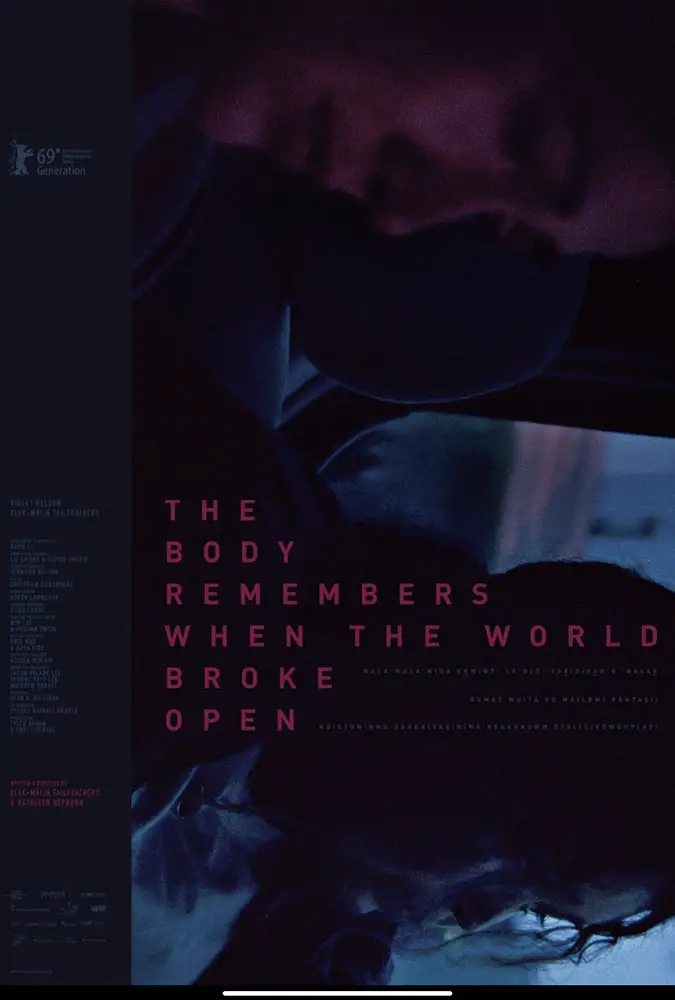

The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open is a genuine social realist film and the fact that it is shot in real-time only heightens the sense of reality. Everything is authentic, thus, one might or might not appreciate scenes such as the one where the protagonist goes to the bathroom to pee (in real-time!), looks for feminine pads, or long moment of silence with the sound of a dryer drying Rosie’ soaked hoodie, but this is also what makes the movie so powerful. One can see The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open as an important story about two women, strangers who have so much in common and yet are worlds apart. The beauty of the film is also that the two individuals, living blocks from each other in a gentrified neighborhood with invisible barriers, may have never met, or might never see each other again – or want to – even after the eventful afternoon.

"…a great story to tell about the harsh realities of indigenous women, or simply women everywhere in the world."