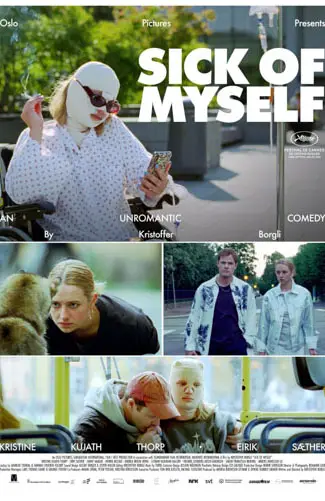

It’s nearly impossible to walk away from viewing Norwegian writer-director Kristoffer Borgli’s Sick of Myself without harboring intense disdain for serial narcissist Signe (Kristine Kujath Thorp) and her slimy boyfriend Thomas (Eirik Sæther). She is an insecure young woman desperate for recognition. He is a pretentious modern artist who thrives on crafting “art” from stolen furniture. The two of them make an unforgettable impression during the film’s opening sequence after they abscond with a $2300 bottle of wine from a high-end Oslo restaurant. Surely these two aren’t going to be the focus of this comedic drama, right? Oh, but they are! Viewers who need their films to have likable characters would be wise to steer clear.

The narrative starts in earnest when, in the aftermath of a vicious dog attack, Signe saves a woman from bleeding to death at the cafe where she works. She’s thrilled about being viewed as a hero. But the true source of her happiness is the opportunity to shift the attention of her friends from Thomas’ asinine art projects to her new role as savior. Thomas’ artwork makes this celebration premature, though.

It’s at this point that Signe begins to find creative ways to play victim, thereupon garnering the sympathy of others. She starts off by faking a dangerous nut allergy. Signe ultimately begins subjecting herself to an experimental Russian prescription known to cause unsightly and permanent skin damage. Her plan works, and her disfigured skin soon makes her the talk of the town.

“Signe ultimately begins subjecting herself to an experimental Russian prescription…”

Borgli pushes the film down a rabbit hole of cynical one-upmanship as Signe keeps upping the ante to get the results she’s striving for. Sick of Myself lacks for subtlety once Signe struggles to separate her delusions of grandeur from reality. However, it still paves the way for important conversations about modern culture’s obsession with identity and its potential use of victimhood as a means to advance one’s position. This sentiment is especially on display when Signe is recruited for a modeling agency specializing in representing and exhibiting individuals with various disabilities.

It’s clear that the filmmaker is unafraid of confronting the controversy surrounding the potential commodification of victimhood. Signe’s method of causing her own deformities is an extreme case, but we also can’t be blind to the real-life currency in emphasizing or overplaying perceived disadvantages and subsequently turning them into advantages. Thorp’s performance carries the film with the help of some truly unsettling makeup. Able to charm at will, her character is intensely unlikable, but that’s simply an indication of the actor’s effectiveness in the role.

The film goes too far at points, and the gradual progression of Signe’s narcissism is more successful than when the story descends into nightmarish sequences. That being said, though, the conversations Sick of Myself are bound to inspire are more than worth investing one’s time. If our increasingly desperate need for attention can result in such uncompromising measures, we’re certainly living in unprecedented times if a solid resume isn’t enough. Dark and uncomfortably funny, this work showcases a filmmaker acutely aware of the nuances of modern society.

"…dark and uncomfortably funny..."