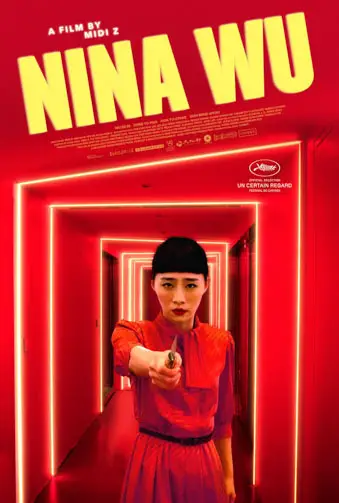

NEW TO VOD! Nina Wu, the latest feature from Taiwanese auteur Midi Z, firmly establishes him as one of the leaders of the latest wave of New Taiwanese Cinema. While his previous drama, The Road to Mandalay, showcased his keen eye for social realism, Nina Wu is suffused with visual poetry – all stark-reds and grainy yellows – and a dream-like (or nightmarish, depending on how you view it) atmosphere. It’s a portrait of a country experiencing significant sociopolitical changes. By focusing on its filmmaking industry, Z takes advantage of the opportunity to experiment visually, thematically, and narratively – at times, to the film’s detriment.

Said industry is an easy target when it comes to exemplifying a country’s inherent, still-prevailing gender inequality. It also hits close to home, what with the recent Weinstein-spawned worldwide takedowns of powerful filmmaking titans who turned out to be sexual predators. Z digs into the subject with gusto, following the plight of an eager, struggling young actress, the titular Nina Wu (Ke-XI Wu), who receives the opportunity of a lifetime: to star in a big-budget blockbuster that is about female emancipation, no less. The catch? It involves full-frontal nudity, a director who’s an as*hole, and a sleazy producer who makes being an as*hole seem like a quirky character trait.

Nina resolutely signs on and stoically withstands emotional and physical abuse, including being choked and slapped, to reach the finish line: international fame. This is where Nina Wu derails, its first half’s laser-focus, steely reserve, and flirtation with satire suddenly replaced by soapy sentiments and a meandering tone. Nina visits her sick mother, reconnects with her humble past, begs Kiki (Vivian Sung), her true love from her theater days, to get back together, and then it all devolves into psycho (predator?)-sexual thriller territory.

“…stoically withstands emotional and physical abuse, including being choked and slapped, to reach the finish line: international fame.”

Thankfully, Z is too shrewd a filmmaker to let the film completely run away from him. Even when it doesn’t gel, Nina Wu compels. Numerous scenes stand out. A car almost runs Nina over on set, and no one even notices, and she’s ultimately okay with it. Similarly, no one rushes to Nina’s help when a boat she’s on blows up. Her suggestions about adding verisimilitude are either shut down or disregarded. The director makes Nina strike Kama Sutra-like poses with two male actors. In another instance, auditioning actresses bark like dogs to get the part.

A lizard caught in a scalding hot lampshade; a cockroach climbing out of a cup onto Nina’s arm; Nina suspended in water as if floating in a vacuum – this sort of heightened imagery, along with the almost-neon color palette, serves to underscore both the appeal and the repellent nature of the film business, one that pits women against each other to the satisfaction of perverted execs. Once the much-sought-after fame is achieved, Nina throws a retrospective glance back at the road that led her there. She wonders if she’s made it, if it was worth it to sacrifice her identity, or if she’s merely another pawn of her country’s regime, a dupe sucked into the system.

Ke-Xi Wu is splendid. She co-wrote the film based on her experiences, which certainly imbues her performance with the verisimilitude for which her Nina aches. She and Z have worked together before and prove that they make for a truly symbiotic relationship. He coaxes perhaps the greatest performance of Wu’s career, and she anchors Z’s film even when it threatens to sink under the weight of its ambitions.

If only the cast and crew had the courage of their convictions and maintained the near-perfection of the film’s first half. Despite the blemishes, Nina Wu marks another timely, visceral entry from one of our most exciting filmmakers.

"…perhaps the greatest performance of Wu's career..."