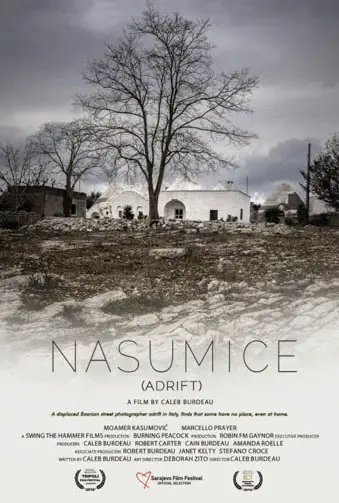

Those displaced from their homeland by war, violence, or oppression know. Regardless of whether they had to flee 40 years ago or four months ago from Vietnam, Nicaragua, Congo, Iraq, or Syria, they know. They know all too well the unanchored feeling brought about by displacement. Director Caleb Burdeau’s Nasumice (aka Adrift) brilliantly captures the melancholy of those set adrift by exile. In the opening scenes, the camera glides along the canals of Venice. This, however, is not the idyllic Venice of tourist postcards. We see a casket loaded onto a gondola. The filmmaker, just like the novelist Thomas Mann in Death in Venice, signals that the stench of death has always wafted along the waterways.

We meet Elvis—played with subtle brilliance by Moamer Kasumović—as he sells photographs to tourists along the canals. He meets a Mack the Knife type with the elegant name of Rodolfo Valentino II. The enigmatic hustler is played with a balance of charm, wisdom, and playfulness by Marcello Prayer. Upon meeting, Rodolfo sings the praises of the sea near his hometown of Puglia and invites Elvis to visit him there. He reminisces to Rodolfo about the mountains surrounding Sarajevo.

Nasumice is set in 1994, at the height of the Balkan conflict. Sarajevo, and the entirety of Bosnia, witnessed some of the worst fighting on European soil. It devastated lives, split neighbors along ethnic and sectarian lines, and even destroyed Bosnia’s most significant UNESCO World Heritage Site, The Stari Most Bridge. Through the use of discolored and sepia-toned flashbacks reminiscent of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, Burdeau makes us aware that even if Elvis does not express it outwardly, he carries with him the haunting memories of the Bosnian bloodbath—images of fleeing individuals, fires, buildings pockmarked by bullets, and stagnant pools of fetid water. Throughout, the director treats the viewer to sublime shots of birds. We are not sure if these birds symbolize the migratory distances covered by exiles or, as some images show birds startled into flight, if they represent the jarring of nerves by loud gunshots and shelling —the ambiguity works in these scenes.

“…he carries with him the haunting memories of the Bosnian bloodbath…”

Elvis continues drifting from Venice to Rome and eventually to Puglia, where he pays Rodolfo a surprise visit. The movie’s visual language effectively contrasts Elvis’ rootlessness with Rodolfo’s frozen-in-time hometown—peasants work the land, transportation around town is done on tractors, and older men play games of bocce using rocks. The duo enters a bar where Italian news buzzes in the background describing the butchery in Bosnia. The men in the bar pay little mind to the report. The newscast seems to remind Elvis of the pain he had to flee from.

Nasumice works because Burdeau achieves the golden rule of storytelling: show, don’t tell. We can see Elvis internally wrestling with his rootlessness when he lingers over Rodolfo’s family portraits. The filmmaker does not need to give a historical exposition of the Balkan War. He shows us moments in which dark memories of war pierce through the main character’s consciousness. War crushes the human spirit, but it is even more disheartening when neighbor fights neighbor—Bosnian, Croat, Serb, Albanian.

Such conflicts scar people physically and psychologically, as in the case of Elvis. As divisions in the US lead us at full gallop toward irreparable disunity from our neighbors, Nasumice is a warning of the damage that lies waiting for us and proves Burdeau is a talent worth following.

"…captures the melancholy of those set adrift by exile."