There is no doubt that Kaufman’s film is stirring and informative. However, the technical aspects of Nasrin leave a bit to be desired. For instance, even though there are titles indicating place and time, the movie jumps around quite a bit. As much as I feel as though too many titles would be a distraction in any film, in this case, their clarification might have facilitated the viewer to discern the where and when of certain occurrences. Additionally, the majority of the movie is filmed via a hand-held camera, but the news footage Kaufman includes is, of course, just as shaky. Therefore, without any differentiating factor (for example, a distinguishable color tone), it’s tough to ascertain if we are watching filmed footage for the documentary or contemporary news footage.

But it’s Nasrin’s story that we are here for, and it is one that needs to be told. Through letters written to her daughter, Mehraveh (there is also a son), and her husband, Reza Khandan, which are read in voiceover by Olivia Colman, warmth and tenderness shines through, rare in depictions of tough-as-nails lawyers in any country. Both aspects of this woman coexist seamlessly in Nasrin.

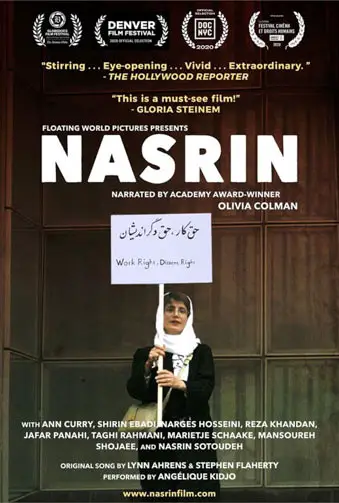

“…stirring and informative.”

The world needs more people like Nasrin Sotoudeh. Here is a woman who lives her life in an outrageously tyrannical society, working as a human rights attorney defending people who challenge draconian laws, many of which are intended to specifically suppress the rights of women nationwide. It’s a dangerous position, yet Nasrin forges ahead, unafraid to push back against the oppressors of her fellow countrypeople.

At the end of Nasrin, she acknowledges that while the women’s rights movement in Iran isn’t over, the work she and her fellow activists do is a vital step in the process. For that, she says, “I should have the right to be happy.” This is fortitude writ large.

Nasrin screened at 2020 DOC NYC.

"…the world needs more people like Nasrin Sotoudeh."