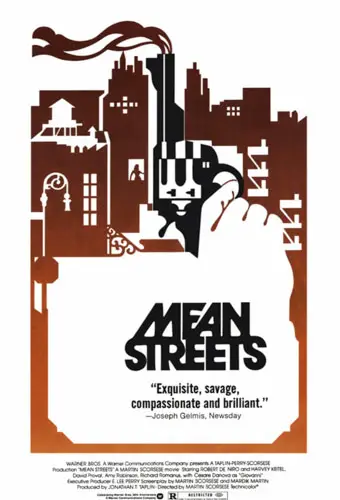

TCM CLASSIC FILM FESTIVAL 2021 REVIEW! Mean Streets is the sort of movie that pours out of you: a projectile vomiting of experiences, influences, ideas, and feelings, none of which can be reconciled. Each of them contradicts the other, making any attempt at reason or structure a nonstarter. What you end up getting is a story that has an extraordinary breadth and freedom of movement while small in budget and geography. In watching Martin Scorsese‘s film for the sixth or seventh time, there’s still the feeling that it could go anywhere, that anything could happen.

That unpredictability, while compelling, isn’t exactly unprecedented. Before and after Mean Streets, the work of aspiring filmmakers has often included at least one movie that’s less of a story and more a pure expression or an attempt to make sense of their little world up to that point. I’m thinking about Fellini’s I Vitelloni or Linklater’s Dazed and Confused.

These are movies where young people are treading or actively navigating the transition between childhood and adulthood, with varying degrees of success and gameness. They’re set in specific locations and cultures, with their own unwritten rules of engagement. True to life, there is no story but many stories. Some have no beginnings, some have abrupt endings, and others are the other way around, but there’s a truthfulness that can’t be replicated in act-based structures or through character arcs.

“…Charlie has an open line of his own with the Almighty. His inner dialogue with God [is] casual but frustrated…”

Of these movies, Mean Streets is the best. It’s the best because it’s ruthlessly cool — a forgotten virtue. When Johnny Boy (a mop-topped Robert De Niro) enters the bar in slow motion with a woman on each arm, both of them taller than he is, to the anthem of aggression that is “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” there’s nowhere you’d rather be in that moment. It’s in the dialogue, too, which ranges from the mundane to the philosophical (“you don’t f*ck around with the infinite”) to the wordplay of Abbott and Costello — a trifecta still very much alive in The Irishman. Much of it is improvised, as well, which gives it that Cassavetes brand of authenticity. None of the dialogue feels loaded; it pops out like a jab. One character explains his lifelong desire to purchase a live tiger with “William Blake and all that.”

But the main character is Charlie (Harvey Keitel), who is, one can safely assume, a proxy for the filmmaker. Established by the famous opening line, Charlie has an open line of his own with the Almighty. His inner dialogue with God — casual but frustrated, like old friends who know each other too well — comes and goes but is always an anchor to something foundational when chaos enters the room. Chaos, of course, takes the form of Johnny Boy, who’s brilliantly introduced with a non-sequitur of a scene in which he blows up a mailbox for no other reason than because you’re not supposed to. He is the Dean Moriarty to Charlie’s Sal Paradise. You envy and pity Johnny Boy; you want to be and to kill him.

Rock’ n’ roll, religion, violence, ambition, lust, war, growing up, and community are just some of the active players in Mean Streets. The streets aren’t mean, necessarily, as that would insinuate some level of malice, but they are unflinching and apathetic to whoever you are and whoever you’re trying to be. As the follow-up to Who’s That Knocking at My Door and Boxcar Bertha (one of only two whiffs in Scorsese’s long career), Mean Streets was the clearest sign yet that not only was he going to be great, but he already was. The scene in which Charlie tests and provokes the flame perfectly elucidates the spirit of the so-called “New Hollywood.” Should a character in today’s Hollywood come into contact with the same flame, he would hold his breath so as not to risk blowing it out.

Mean Streets screened as part of the 2021 TCM Classic Film Festival.

"…it's ruthlessly cool..."