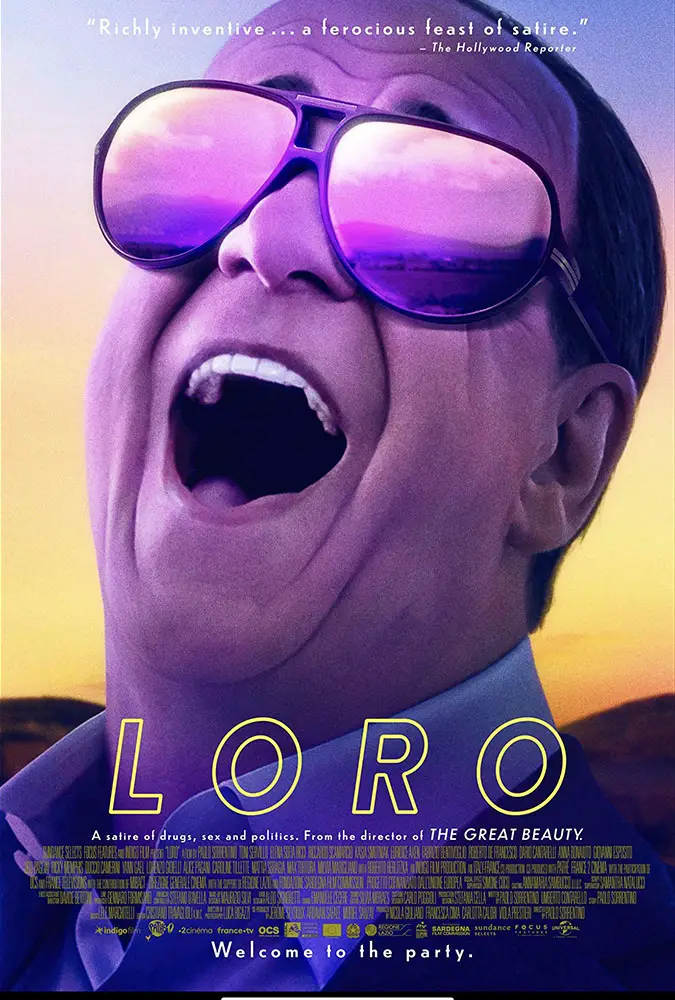

Loro, directed by Paolo Sorrentino, is non-judgmental, but it isn’t indifferent. Instead of shaking its finger at its subjects, it shows them for what they are—or could be—in the giddiest way imaginable. The two degenerates in question are Sergio (Riccardo Scamarcio) and Silvio (Toni Servillo), one of which is a mover-and-shaker with dollar sign pupils, while the other is the prime minister of Italy. We meet them only after first witnessing the untimely demise of a sheep that watches game shows. That’s as good a way to start a story as any.

The first third or so of the movie is dedicated to Sergio. He’s a horndog of the highest caliber, which renders him uniquely qualified for his profession: an agent of sorts, who uses his clients less for their talents and more as walking, talking bargaining chips for important, high-ranking men. Theirs are the heads that Sergio uses as a stairway to power, influence, riches, women, or whatever it is he hopes to find up there that can’t be found down here. The final head on that stairway belongs to Silvio, the attention of whom Sergio hopes to gain by throwing a raucous party within sight of Silvio’s estate. With Silvio, we get a convincing caricature of the politician. He’s a raging narcissist and a deceptive wordsmith, but still a human underneath his silk pajamas, having inherited the good with the bad.

“…a raging narcissist and a deceptive wordsmith, but still a human underneath his silk pajamas…”

Could the movie be accused of the “style over substance” claim that so many keep within arms’ length? Yes, and that’s why it’s great. Style is all that really matters, in all forms of expression, but especially the movies. You can have style without substance, but not the other around—in that case, it would just be a talking-to. It’s what sets writers apart from regular folks—everybody has stories, but only writers have the style to make stories readable. Sorrentino’s ability to make a movie watchable is without question. His movie is made of moments, that—while linear—don’t get hung up in the past and future of continuity, but cherish themselves. It’s like the movie is self-aware, sees its end approaching, and is smelling every rose.

Like other filmmakers before him—Robert Altman comes to mind—Sorrentino prefers to tell his stories through a visual arrangement, rather than a written one. He takes “show, don’t tell” to its natural conclusion. At the party designed to capture Silvio’s attention, one of Sergio’s youngest guests doesn’t drink or do drugs—the only of her kind at the party. When the party’s over, and everyone is in some post-orgy haze, sprawled out wherever they fell like trash on the sidewalk, she’s the only one still dancing, life essence intact. It’s a simple image and contrast, but care and aesthetics elevate it to high truth.

If being dull is the cardinal sin of the movies, as Capra supposedly said, then Sorrentino is a saint. There’s not a dull moment in Loro, whether it’s the hypersexual, reality-bending party scenes or the quiet backroom conversations where the truth comes at the characters so unexpectedly, they don’t have time to prepare their usual defenses. All of it is visceral pleasure at an eye-bleeding volume.

"…the untimely demise of a sheep that watches game shows."