Upon hearing Isaac’s name during a poem recital at one of Gediminas’s raucous parties, Andrius is sent into a panicked frenzy. He proceeds to confront Gediminas about the past that haunts him, flabbergasted at the man’s ability to move on. In the meantime, an investigation into the massacre, led by the perseverant KGB officer Kazimieras (Martynas Nedzinskas), reopens. Kazimieras believes that there’s a conspiracy, that the events and names of the script match too closely to those of the Kaunas pogrom. The director confidently controls this vortex of events until it all culminates in devastation and salvation.

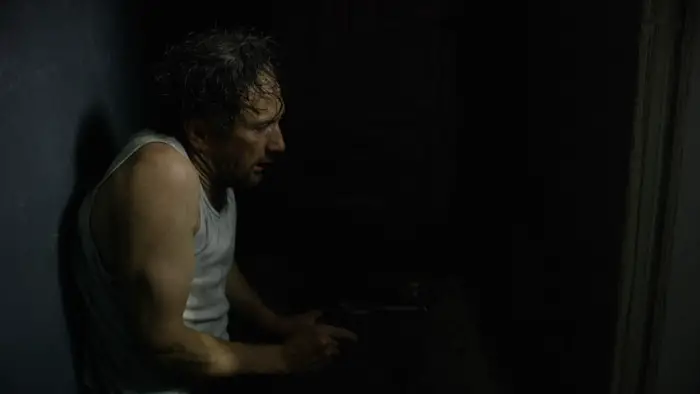

The influence of Polish filmmaker Pawel Pawilkowski on Isaac is evident, as is the Soviet-era cinema stylization, not to mention all the Kafkaesque imagery. Matulevičius makes this explosive concoction his own. No words can do justice to Narvydas Naujalis’s fluid cinematography; he boldly switches between black-and-white and color, his continuously panning camera capturing both the subtlest of expressions and the splendor of the human emotional spectrum. Characters live in shabby apartments with cracked walls and exposed rusty radiators. This misery is contrasted against the glamorized world of a film set. When moments of grisly violence arrive, they resemble sharp stabs through a dreamlike veneer.

“The filmmaker rarely steps wrong.”

The filmmaker rarely steps wrong. Whether it’s Elena washing her elderly mother in the tub, an anachronistic dance sequence, or a searing confrontation between Andrius and Gediminas involving vodka and a gun, Matulevičius keeps his audience on edge. He is a masterful puppeteer with his strings firmly attached to the viewer’s emotions. It’s never manipulative, always raw, honest, and uncompromising.

“You are what you are. Without your memories, you cease to exist,” Gediminas says at one point. We have the capacity to forget – or pretend to forget – about the atrocities of our past, what humans are capable of when suddenly allowed to enact their darkest fantasies. We may later justify it to ourselves. Some of us may even succeed. Yet guilt eats away at most of us until we lose our loved ones, and all that’s left is that tumor-like sadness inside. Isaac may reopen some national wounds, but sometimes there’s a lingering infection underneath the scab that needs to be cured.

Isaac screened at the 2021 Slamdance Film Festival.

"…moments of grisly violence...resemble sharp stabs through a dreamlike veneer."