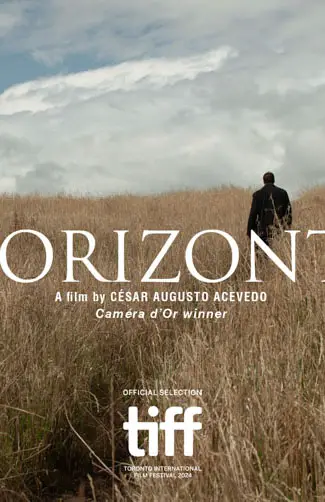

TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2024 REVIEW! The subject of the Colombian feature film Horizonte by writer/director César Augusto Acevedo is the cost of bananas. The real cost of bananas. When Alan Moore wrote about the cold war in his ’88 graphic novel, Brought to Light, he used swimming pools full of blood (A litre per person, at 20,000 litres each) to measure the murder in Central America. His tally back then was eight pools.

And the fighting in Columbia hasn’t stopped. In fact, they have had a civil war since the ’50s. Capitalism looks deranged when we see the fight it had with perceived communism in the American backyard. Despite U.S. beliefs to the contrary Russia had a marginal strategic interest in Central America, seeing it as too far from them and too close to the U.S. to be worth the risk of conflict. The CIA committed itself to fighting worker’s rights there anyway.

It is a rare distinction to be killed in something as funny sounding as a ‘banana massacre’, but 2,000 employees of Chiquita (née United Fruit Company) were. Back in 1928, the Colombian army shot them for protesting. All in the past, you may shrug, except this June Chiquita was judged to have funded death squads in Columbia in the ’80s and ’90s to terrorise their workforce again.

The tale told by Horizonte is of two despairing spirits seeking peace; a young man, Basilio (a magnetic Claudio Cataño) who worked for the death squads, and his mother Ines (a graceful, soulful Paulina García). He has lost all hope whereas it is all she has left. They haunt the places of their past, connecting with other spirits in the beautiful landscapes where Basilio killed.

“The tale here is of two despairing spirits seeking peace…”

Horizonte has some magical images that are suitable tributes to Acevedo’s countryman Gabriel Garcia Marquez; a house rises into the sky, a lace of roots and soil tumbling through space beneath it, two lone figures are washed from a street by a river of caskets, a murderer kneels before a godhead made of the lives he destroyed, blinding himself in anguish. The photography, by Mateo Guzmán, is all majestic.

Probably the most famous Hollywood movie about cold war maneuvering in Latin America remains Oliver Stone’s Salvador from way back in ’86. Other than that, its popular representation is as narco villains for heroes to blast through. You could argue that Predator 2 (yes, the one in L.A.) accidentally says more about Latin America than the rest of Hollywood’s tame blockbusting.

It feels there remains a need for more of these stories, though, as it’s hard to tell where this film’s drive is. It has two particularly interesting leads, Basilio and Ines, but the darkness needs some relief, as it becomes a challenge. The leads are dignified and composed throughout, but the casting and wardrobe felt on the nose. This is a film centered on a sad mother and a wicked son. It didn’t need them made up as a sad-looking lady and a wicked-looking man? Rather than reinforce character, it smooths out the grain.

Towards the end, I started to wonder what it might have been like if neither ghost talked. The conversations between Cataño and García were beautifully played, but the tone doesn’t change much for two hours, and the pacing has a number of testing longueurs.

“You have a heart, and that’s the worst part,” explains a murder victim to Basilio. “Even now, you still believe in what you did.” And, it feels a little like Acevado is stuck with a similar predicament. Horizonte is a terrific film, on an important topic, so it is frustrating that it feels cautious, and drawn out.

There is a lot marvelous and beautiful within his tale of apocalypse, and it is an essential contribution to Columbian cinema, but the earnest presentation can make it seem a long road at times.

Horizonte screened at the 2024 Toronto International Film Festival.

"…an essential contribution to Columbian cinema..."