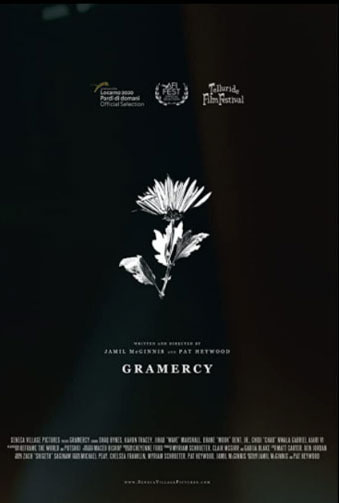

In Gramercy, directors Pat Heywood and Jamil McGinnis beautifully craft a story around brotherhood, masculinity, and depression. Over the course of 22 minutes, they document a relatively young New Jersey native named Shaq (Shaq Bynes), who returns to his hometown where he interacts with familiar faces. Unbeknownst to anyone, Shaq is wrestling with depression, but instead of confronting those feelings, he masks them.

The movie opens with three young black men smoking in a local park. No words are spoken as the three men are comfortable with each other, sharing the joint and relishing the silence. Shaq eventually leaves the picnic table to take in the view of the encircling trees and distant city. However, when glancing back, he appears dejected. The camera gradually circles around to reveal an empty picnic table; the other men have vanished, alluding to the passing of time. It’s been six months since Shaq up and left, his friends wondering where he went, while viewers are wondering why he left in the first place.

For the majority of the short film, the mystery behind Shaq’s crippling depression is traced back to a tragic incident, although the details of that incident are intentionally vague. In order to deal with the depression, Shaq chooses to disregard it completely by striving for normalcy, which essentially means going to parties and hanging out with old friends, including Karon (Karon Tracey) and Wave (Jihad Marshall). But the more Shaq ignores his depression, the more isolated he becomes.

“…Shaq’s crippling depression is traced back to a tragic incident…”

Depression isn’t always easy to detect; it can hide behind a smile or a simple, innocuous gesture. When we first meet Shaq, he’s in a tacitly depressive state, which propels him into an overwhelming haze of self-isolation—a furtive form of psychological discomfort that steadily eats away at the host until they feel virtually alone. Gramercy doesn’t tell the whole story or even a considerable slice of what caused Shaq’s depression and how he’s pushed to confront it. Even so, the movie is tremendously honest and quietly powerful, capturing a snippet of what Shaq goes through as a young man plagued by unsavory thoughts in a masculine environment where disclosing your feelings isn’t exactly common practice.

The film wouldn’t be as effective if not for Shaq Bynes’ magnificently subdued performance. Bynes exudes enough facial expressions and meandering gazes to communicate the character’s stifled dolor nicely. The camerawork is gorgeously smooth, remaining fixed from Shaq’s perspective. Zachary Saginaw’s exceedingly varied and wistful score mixes smooth jazz, hip-hop, and electronic music, magnifying Shaq’s attempts to return to normalcy.

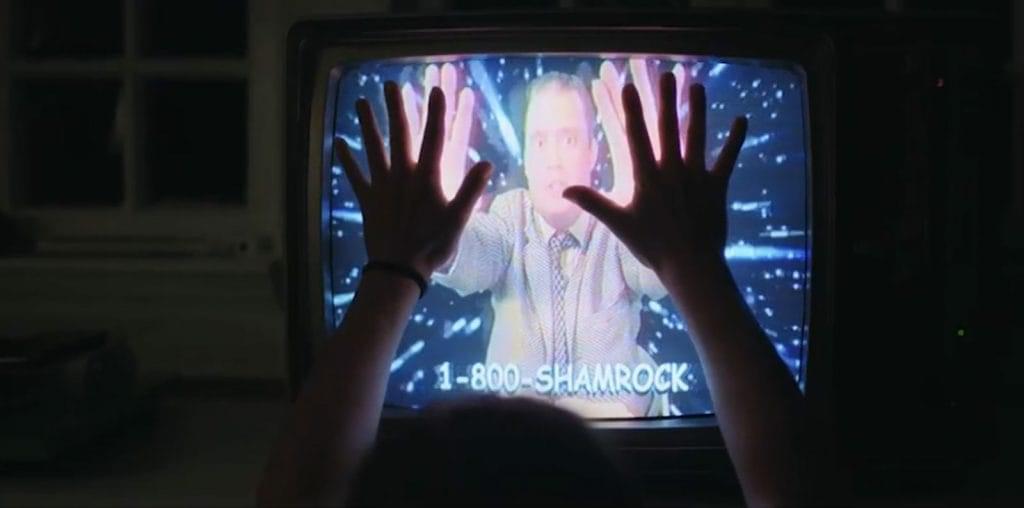

The movie exercises an ethereal, poetic style that’s perfectly nurtured by skilled cinematographer Maceo Bishop, whose color palette perpetually shifts from vivid color to moody black and white, mainly to reinforce what it is like living with depression. A gravely depressed person may observe their surroundings as a world of achromatic gloom. However, there are a few divinely composed, vibrant shots of nature that often place Shaq in the heart of it, symbolizing his hidden desire to share his feelings and truly unwind in his surroundings. A Langston Hughes poem, titled “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” is even utilized, referenced in voice-over, and coinciding with Shaq’s muted journey of grief.

Jamil McGinnis and Pat Heywood’s Gramercy is a raw portrait of grief and brotherhood that feels and looks like poetry. Despite there being loose threads, the short’s ability to avoid embellished interactions and a swift solution speak volumes to the film’s truthfulness.

"…a raw portrait of grief and brotherhood that feels and looks like poetry."