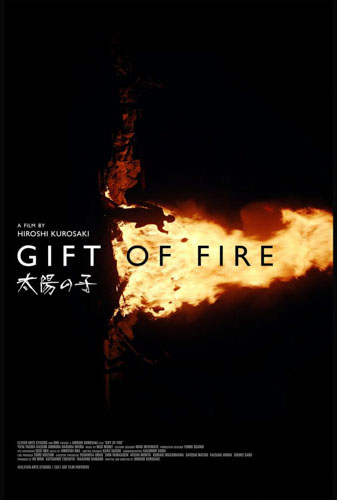

The title of Hiroshi Kurosaki’s splendid Gift of Fire is a direct reference to Prometheus, who bestowed fire upon humanity, both a gift and a curse. Fire gave us warmth, provided us with light and cooked meals, but it also led to destruction and war. In the context of the film’s WWII setting – specifically, a claustrophobic Japanese lab and its sweaty scientists developing the atomic bomb – the title’s sardonic undertone becomes especially apparent. Humanity seems incapable of regarding its scientific discoveries as gifts with the potential to prolong life and end all conflict, utilizing them instead to bring about more devastation.

Kurosaki masterfully explores the beauty and terror of scientific progress, focusing on the months before the U.S. dropped bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A group of young male researchers, led by Shu (Yûya Yagira), receive much-coveted bright-yellow uranium nitrate. Their goal: to achieve nuclear fission, or, as their boss Arakatsu (Jun Kunimura) states, “to unleash the power of the atom.” While their Japanese brothers and sisters are dying on the battlefield, our heroes race to beat the Russians and Americans, yet supplies are sparse, the pressure from authorities is immense, and their patience is beginning to run out.

The filmmaker’s skill and confidence as both writer and director are apparent from the first few minutes. There’s a palpable sense of excitement of discovery, supplemented by underlying melancholia. Though quite meticulous when it comes to the science, Gift of Fire is rarely dry, self-important, or complicated; it makes extremely complex equations and formulas seem, well, fun is probably not the word, but certainly engrossing.

“…researchers…receive much-coveted bright-yellow uranium nitrate. Their goal: to achieve nuclear fission…”

Kurosaki reflects on the horrors of war by allowing them to unravel in the background, all the more gut-wrenching for how understated they are: a cheerful son returning home from witnessing unimaginable terrors in a losing battle; his mother, sensing his grief and grieving with/for him; a suicide attempt; a demolished home. There’s little bombast, the worst horrors left for us to imagine.

“What do you think about scientists building weapons in the first place?” a character inquires, summarizing the chief theme. We pursue greater knowledge but use it to destroy what we painstakingly built. With nations competing instead of uniting, it’s the matter of who attains the dangerous wisdom first. When the stakes rise to levels this high, is there a choice? “Whoever builds the bomb first will decide the fate of the world,” another scientist remarks. Gift of Fire studies the effect this moral conundrum has on the researchers. One of them attempts to leave the lab for the war, another tries to end his life, and another gradually loses it, wishing to observe the destruction of a city from a high point, to see the bomb’s effect in real-time.

A few negligible missteps – Peter Stormare’s English narration, tacked-on and off-putting, does little to forward the plot; some flashbacks slow down the proceedings – do little to blemish the overall experience. Ingenious and lyrical notions are explored, such as atoms continuing after our deaths, “circulating through time,” or Shu seeing a “beautiful light” in particles. The director compels with moments both small and epic: a prolonged, impassioned fight in a lab; a mournful violin by the fire in the woods; a character walking out of the train to silently witness the flattening of Hiroshima.

Ultimately, Gift of Fire is about the gift of kindness we bestow upon each other, the tiny light of fusion that keeps us going, keeps us breaking boundaries, sometimes at our own expense. “There’s no right or wrong,” the film argues, “there’s only the truth.”

"…masterfully explores the beauty and terror of scientific progress..."