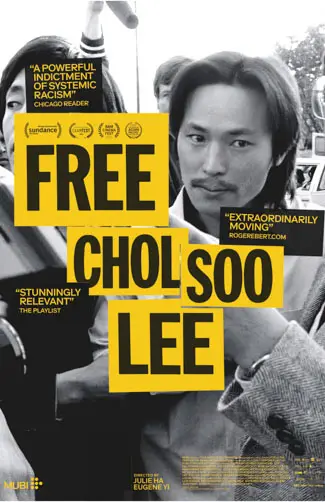

OPENING IN NEW YORK! Chol Soo Lee’s case can only be described as Kafkaesque. Directors Julie Ha and Eugene Yi’s documentary, Free Chol Soo Lee, take us to San Francisco’s Chinatown in the 70s. A Chinese gang puts out a hit on another gang member. The killer shoots the rogue gang member in the street in broad daylight. The killer flees. In the police’s haste to nab a suspect, they hit upon Chol Soo Lee. Lee had a criminal record and happened to be the victim’s neighbor. The police find a gun in Lee’s apartment that matches the gun suspected in the murder.

A lesser documentary would have piled on every institutional blunder and ill-fated twist in Lee’s case in quickfire succession. Instead, Ha and Yi allow Lee’s personal story to unfold as they slowly drip details of how Lee came to be sentenced to death. The police’s primary witnesses were all white. These witnesses all identified Lee in a physical lineup. Putting aside the police’s maddening disregard for the phenomenon of cross-racial identification, they went so far as to bury the file of an Asian witness that was a mere 12 feet away from the scene of the crime. That Asian witness could have helped Lee’s case. In addition, the juries in Lee’s cases were all white. The police’s own mugshot book had a racist Chinese cartoon on the cover.

I mention that last detail not only as evidence of racism on the part of the San Francisco police department but also to highlight what is perhaps the most absurd and maddening detail in the Lee case. Several TV news reports and newspapers identified Lee as Chinese. Lee was Korean! In fact, it would have been very unlikely, given the cultural and linguistic gulfs between the Chinese and Korean communities, that Chinese gangs would have employed a Korean killer to carry out a murder.

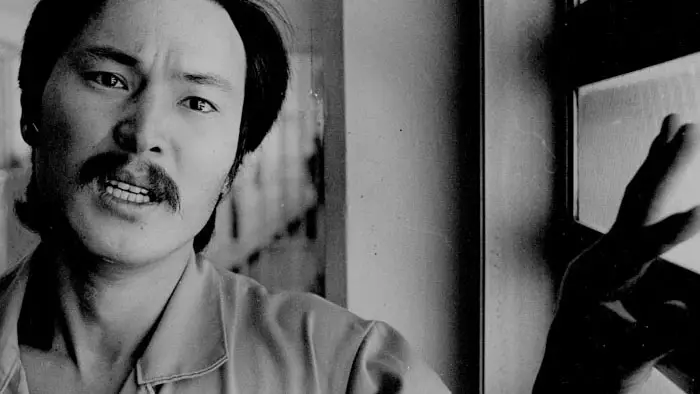

Chol Soo Lee , served nine years in prison for Chinatown murder, but will get new trial, July 30, 1982 Photo ran 08/02/1982, P. 2 (Photo by John O’Hara/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

“In the police’s haste to nab a suspect, they hit upon Chol Soo Lee…”

Free Chol Soo Lee shines when spotlighting Lee’s personal story. His mother left him behind at a young age in Korea. He was raised in poverty by an aunt and uncle. Lee’s mother later did return and brought him to the United States. In the U.S., Lee led a lonely and alienated existence. He had a hard time with English, had trouble with a school system focused on assimilating Chinese students, and did not understand differences in Asian cultures. Lee went from being put in a delinquent juvenile facility to a psychiatric ward. These experiences led him to adopt an even tougher persona.

Ha and Yi, through the figure of Lee, are making a grand statement about the Asian and immigrant experience. Immigrants like Lee often lead lonely precarious lives. As K.W. Lee — an investigative reporter who advocated for and befriended Lee — puts it, there’s a “thin line between his (Lee) fate and mine.” Lee’s case galvanized a group of Asian activists that advocated for his innocence. While the narrative focuses on Lee’s story, it also looks at the activists who worked for Asian rights, dignity, and justice.

There’s a throughline in this country’s history that goes from The Asian Exclusion Act to Chol Soo Lee’s case to publicized cases in the last few years of hate crimes against Asians. Free Chol Soo Lee reminds us that when we sit on the sideline and do not actively fight against discrimination and the stereotyping of Asians, real people, such as Chol Soo Lee, suffer.

"…shines..."