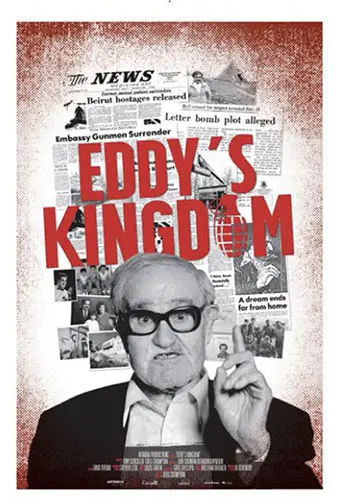

The line between eternal optimism and delusion can be quite thin and even porous. Director Greg Crompton’s documentary Eddy’s Kingdom examines this line. Eddy Haymour is old, seemingly sweet, and harmless. He looks like the most adorable grandfather imaginable. Behind the cuteness lies a whirlwind of unexpected character traits and intensity. Haymour migrated to Canada from Lebanon in 1955. He arrived knowing only a few words in English, became a barber, then business owner, and started a family. Thus far, his story reads like a typical immigrant tale. However, his life takes several left turns.

Haymour became fixated on a small island in the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia. His dream was to build a Middle Eastern (an extremely problematic geographic designation for predominantly Muslim countries stretching from Morocco to Iraq that offer significant cultural variation) amusement park containing an 18-hole mini-golf course, chariots pulled by horses, minarets, a pyramid, and even an ice cream parlor inside the belly of a camel-shaped structure. Apart from the aesthetic objections raised by such a kitschy project, locals in the Okanagan Valley were concerned with the environmental impact. Haymour saw his amusement park as a cultural celebration. Critics accused him of blatant profiteering.

Haymour, having legally bought the island, set the bulldozers loose. As expected, government obstructions and permit games were set in motion to frustrate the amusement park plans. Haymour threatened to kill several government officials, went through several legal trials — at least one of which hinged upon, of all things, brass knuckles — and got sentenced to eleven months in a psychiatric facility. But wait, it does not end there. His fight for the island culminates in Haymour going to Beirut, storming the Canadian embassy, and taking 34 hostages.

“[Eddy Haymour’s] dream was to build a Middle Eastern amusement park…”

Eddy’s Kingdom treads the same ground as documentaries focused on eccentric individuals that, just when you think their obsessive behavior has reached a culmination, it is topped by even more bizarre behavior. Werner Herzog has made a career out of documenting these types of individuals. Errol Morris’s Tabloid is perhaps the Platonic Form for these types of documentaries. Sure, Crompton is not breaking any new ground, and he is certainly not topping Herzog or Morris; however, Haymour’s life, his volatile personality, and determination are fascinating, and by extension, that makes the film a really fun ride.

Regardless of what one thinks of Haymour’s amusement park idea, one cannot help but feel some sympathy for him. One wonders how much of the Canadian government’s obstructions really had to do with environmental preservation and adherence to the law and how much of the spirit behind the obstacles had to do with anti-immigrant attitudes and prejudice toward the “Other.” There are times when Haymour’s paranoia and his animus against the government seem justified. The director does a great job of presenting his subject as a flawed individual and presenting the many flaws of the Canadian government in relation to Haymour. Crompton is also wise to include the perspective of Haymour’s daughters.

While Haymour is admittedly lovable, and his stories would likely entertain anyone sitting next to him, his one-track mind created havoc for his family. Family members recount fights he had with his first and second wife, instances of physical abuse toward them, and even an episode wherein Haymour kidnapped his children and whisked them away to Lebanon. His one-track mind toward his amusement park led to divorces and the dissolution of stability for his children. Obsessive individuals usually hurt those close to them.

Eddy’s Kingdom is ultimately a cautionary tale. Eddy Haymour felt wronged and shamed by the Canadian government. The Canadian government gained an enemy that it wished it had not, an enemy devoted to fighting them until his last day on this mortal coil. Some are shamed and crumple. In the case of Hamour, the shame inflicted upon him by the Canadian government became the gasoline that fueled his life.

"…a really fun ride."