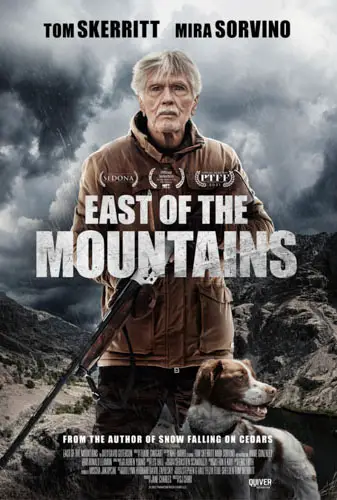

One of the posters to S.J. Chiro’s East of the Mountains portrays a leathery, determined Tom Skerritt holding a rifle, his dog next to him, posing against a picturesque backdrop of mountains immersed in stormy clouds. Everything about the key art suggests an adventure film. While the bulk of the narrative does revolve around Skerritt’s character traversing treacherous terrain, those expecting a lower-budget The Call of the Wild will likely be caught off-guard. An inward journey of self-discovery and a meditation on death, the director’s second feature moves at a leisurely pace, relying on its prevailing mood of poetic melancholia and powerful lead performance to sustain the viewer’s attention.

Retired cardiac surgeon Ben (Tom Skerritt) lives alone with his dog. After finding out that he has terminal cancer – and a consequent failed suicide attempt – he decides to revisit his old stomping grounds in Eastern Washington. The notion of Ben absconding into the wilderness breaks the heart of his estranged daughter Renee (Mira Sorvino). “I just want to go to the mountains and let the dog run around,” he explains to her, resolute in his undertaking.

Things go wrong, of course. his car breaks down, so he simply leaves it behind. Haunted by nostalgia, Ben embraces nature, hunting birds, camping, and even smoking weed. That is until a traumatic altercation with a coyote hunter puts an abrupt end to this idyllic swan-song. Ben ends up befriending a small-town vet, Anita (Annie Gonzalez), before reconnecting with his brother Aidan (Wally Dalton) and finally confronting his demons.

“Haunted by nostalgia, Ben embraces nature, hunting birds, camping, and even smoking weed.”

Treading a fine line between understated and underwhelming, East of the Mountains is about the silence between words, the pauses between the action, that brief moment between inhaling and exhaling. It’s a somber soliloquy that deals with revisiting one’s past, facing one’s guilt, embracing old age and death. Its minimalism threatens to become tiring, rendering the entire ordeal insubstantial; Thane Swigart’s screenplay relies a bit too much on the “less is more” approach. Plot trajectory-wise, of all the paths it could’ve taken, it chooses a well-trodden one.

On the other hand, Skerritt’s introverted performance is a thing of beauty, effortlessly elevating every scene he is in – all of them, in other words – into the realm of nigh-transcendence. The highlight, set in a hotel room, arrives towards the end, the steady camera unflinchingly gazing at Ben’s emotional breakdown. The 88-year-old stalwart projects decades of experience in the subtlest of ways. Aside from Skerritt, Gonzalez and Dalton cast the biggest impressions, the former’s generosity providing a hint of warmth to the frigid narrative and the latter’s white beard deserving of credit all by itself. Sorvino, though second-billed on the misleading poster, is barely in the film.

With a little more flair, drive, or a fresh perspective, East of the Mountains could’ve been a real gem. Instead, it’s a decent little character study about a man facing death, worth a look for its magnificent central performance alone.

"…Skerritt’s introverted performance is a thing of beauty..."