Multiple questions arise, the film’s plot holes as deep as the well around which Don’t Tell a Soul revolves. The boys’ motivations strain credulity. “If he yells loud enough, someone will hear him,” is the kind of nonsense Matt spouts. Why doesn’t Joey just anonymously call the cops, or a neighbor, or drop a note? Would Joey really allow all this torture to happen at the tender age of 15? Would Hamby really risk the chance of the kids calling 911? What’s with the loaded gun being recklessly handed to each other, over and over again? Why doesn’t anyone step in for Joey when he’s getting his a*s handed to him at a party? Why does Joey resort to such an extreme at the end, without so much as giving it a second thought? How do they all just walk away after a mid-afternoon shoot-out in a residential neighborhood?

The questions go on. I’m sure McAulay has answers to most of them. That doesn’t make his movie any less underdeveloped or more coherent. Thankfully, the cast goes a long way in ensuring that even when you ask questions, you won’t give a hoot about the answers. Rainn Wilson has a blast hamming it up as the devious Hamby. “You gotta do the Christian thing,” he tells Joey in one delicious moment. “Are you more afraid of your brother than you are of God?” You’ve never seen Dwight Schrute get this crazy. Mena Suvari is delegated to shaking her head incredulously at the TV news while looking sickly. “What a world,” she mutters, over and over. In a tense moment that quickly turns hilarious, Joey asks her if she still wants her diet soda. “Not right now!” she snaps, trembling.

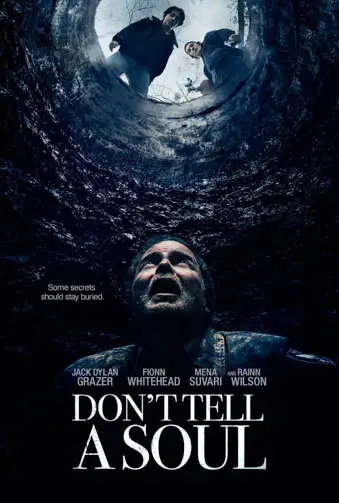

“From the first minute, Don’t Tell a Soul grips you and doesn’t let go…”

Jack Dylan Grazer does his best with an overwritten part: (deep breath) constantly bashed by his brother, seeing the world through his brother’s eyes, caring for his mom, yearning both freedom and control (“I rule the roost!”), being an accomplice to potential murder, being an accomplice to a potential murderer, personifying the angst and misery of a modern adolescent crippled by circumstance. That’s a lot for any actor to handle. But then there’s Fionn Whitehead, saddled with Matt’s character: increasingly crazed, deeming himself the man of the house, fueling his toxicity under the pretense of doing it for ma, his intoxication by his own power trip masking a deep insecurity and resentment, in itself spurred by the loss of his father. Both of the boys deserve major props for making their frankly insane characters believable.

“Sometimes, you wish you could go back in time before life knocked your knees out,” Hamby says, vocalizing McAulay’s Themes. The notion of exploring how a young boy views the world through his manipulative older sibling’s eyes – and how poverty affects that developing worldview – is not a bad one. It’s just delivered haphazardly. I applaud McAulay’s efforts, but Don’t Tell a Soul is at its best when it’s simply having fun as a silly B-flick. Shut your brain off, enjoy, and, like with any guilty pleasure, don’t tell a soul you liked it.

"…You’ve never seen Dwight Schrute get this crazy"